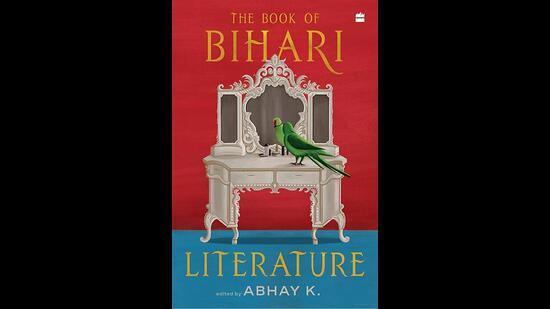

Excerpt: The Book of Bihari Literature edited by Abhay K

Dusk had fallen. A parrot flew on to the verandah and perched on the clothes line. When Reshma saw the bird, she wrapped a stole around her palm, took care to make no noise, and grabbed it with one swift move. A triumphant shriek followed; one that drew everyone at home out to the verandah. The kids were ecstatic at the sight; they pranced all around the parrot. Badi Bi examined it carefully and issued a few instructions: “Rasool, put some ointment on the bird. The crows have poked at it with their sharp beaks. Rahim, bring down the egg basket. We’ll keep it in it till a cage is arranged.”

Muravvat Miyan was sent to the market to get a birdcage. Meanwhile,efforts were made to ensure the parrot was as comfortable as possible in its temporary home. An earthen bowl was filled with water and placed in the egg basket. Salma ran to the backyard and returned with a freshly plucked guava. That, too, was shoved in. Badi Bi’s four grandchildren huddled near the basket, intently observing each little antic of the bird. The parrot seemed to be really thirsty. As it drank hastily from the bowl, the kids broke into loud, wonder-filled laughter.

Within an hour, Muravvat returned with the purchase. The bird was transferred to its new enclosure, which was then suspended from the ceiling. A fistful of chickpeas was soaked to feed it in the morning. To the family, it wasn’t just another renegade parrot that had escaped from someone’s home; they considered it a godsend. Wearied by its harrowing experiences and the day-long starvation, the bird had grown quiet and sickly. It sat still, its head drooping because of the fatigue. Everyone feared that the wounded parrot was slowly dying.

A while later, Muravvat’s wife dragged a bed into the courtyard. Although Badi Bi and her grandkids were quick to lie down, no one really slept. They stayed awake till late, their eyes fixated on the cage.

The next morning, the house was once again abuzz with excitement. Awoken by the parrot’s screech, Muravvat’s wife had run excitedly to the cage. Perhaps the bird was trying to mimic a song. “Parrot, speak. Say ‘Allah, Allah,’” she entreated, holding on to the cage.

The bird immediately sprung to action and trilled. “Say, parrot; say ‘Sita Ram’. Bring me Shiva’s swig.”

“Haye Allah!” exclaimed Muravvat’s wife, visibly shocked. She released her hold on the cage and took a step back, as if recoiling in horror at the sight of a snake.

“Ammi Jaan! Ammi Jaan!” she shrieked.

Alarmed at the noise, Badi Bi and the kids woke up. “What happened? Is the bird dead already?”

Muravvat’s wife dashed towards the bed. “Ammi Jan, this parrot is Hindu. What to do? Should we set it free?”

“So what? Don’t release it,” the kids protested fervently. But Badi Bi suddenly seemed unmindful; she was lost in deep thought. She, too, had once tended to a Hindu parrot. She thought of the time she had eloped with Raghunath Misir, severing ties with her entire world — parents, relatives, community, village and her home — leaving all of it behind. Rechristening Raghunath Misir as Rahmat Miyan, she had devoted her entire life tending to him, just as one tends to a pet parrot. The runaways had settled in a new place and lived a life of obscurity,distant from the people they once called their own. Like a devout Muslim, Rahmat Miyan used to pray five times a day. He was well-regarded in the community. Over the years, he had made a fortune as a doctor of homoeopathy. He had built a house, educated Muravvat Hussain, his only son, and made him capable of leading a respectable life before peacefully exiting the world. No one other than Badi Bi knew his story. But, sometimes, Badi Bi suspected that her son had caught a whiff of their secret. Only Allah can tell if my suspicion is right.

Rahmat Miyan’s last day flashed before Badi Bi’s eyes. He had asked everyone to leave and had spoken to her in private. “Biwi, till this day, I have asked no favours of you. But today, I beg you for something. Won’t you oblige?”

Tears had rolled down her cheeks. She could merely nod in agreement.

“There is a bottle with sacred Ganga water in my trunk. Before I die, please pour a little of that in my mouth,” Rahmat had urged.

When Rahmat Miyan had eloped with Badi Bi, he had first taken her to Haridwar. She had vivid memories of that trip: she remembered how he had bathed in the Ganga, discarded his holy thread in the stream and filled a bottle with the river water. When Badi Bi had sought an explanation, he had promised to do so at an opportune moment. True to his promise, he had clarified it all when the time came. That day, Badi Bi had poured a spoonful of the Ganga water in his mouth, making certain no one saw her. She also recalled that Muravvat, too — knowingly or unknowingly — had poured a little water into his father’s mouth from the same bottle. At the time of his death, Rahmat had softly chanted “Hey Ram, Hey Ram.” How could she ever forget that!

One day, while rummaging through Rahmat Miyan’s trunk for a paper, Muravvat had stumbled upon an old photo. It was the portrait of a tonsured boy in his loincloth. He was wearing padukas and held a bamboo stick over his houlders, tiny bundles tied at both ends. Muravvat had stared at it for a while and then offered his pranam with folded hands before returning it safely to the trunk. Since that day, as far as Badi Bi knew, Muravvat had never felt the need to open the trunk.

“Of all the homes here, the wretch decides to come to ours. I’ll release it at once,” averred Muravvat’s wife.

By now Badi Bi had composed herself. “No, bahu. I will not have it chased away; if it has come to us, it will stay with us,” said Badi Bi, her voice firm.

She spoke with such conviction that Muravvat’s wife did not have the courage to defy her. Instead, Badi Bi turned to Muravvat and said, “Muravvat, yesterday it was put in that profane egg basket. Take it to the Ganga for a holy dip.”

The story was translated from the Bhojpuri by Gautam Chaubey.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Dusk had fallen. A parrot flew on to the verandah and perched on the clothes line. When Reshma saw the bird, she wrapped a stole around her palm, took care to make no noise, and grabbed it with one swift move. A triumphant shriek followed; one that drew everyone at home out to the verandah. The kids were ecstatic at the sight; they pranced all around the parrot. Badi Bi examined it carefully and issued a few instructions: “Rasool, put some ointment on the bird. The crows have poked at it with their sharp beaks. Rahim, bring down the egg basket. We’ll keep it in it till a cage is arranged.”

Muravvat Miyan was sent to the market to get a birdcage. Meanwhile,efforts were made to ensure the parrot was as comfortable as possible in its temporary home. An earthen bowl was filled with water and placed in the egg basket. Salma ran to the backyard and returned with a freshly plucked guava. That, too, was shoved in. Badi Bi’s four grandchildren huddled near the basket, intently observing each little antic of the bird. The parrot seemed to be really thirsty. As it drank hastily from the bowl, the kids broke into loud, wonder-filled laughter.

Within an hour, Muravvat returned with the purchase. The bird was transferred to its new enclosure, which was then suspended from the ceiling. A fistful of chickpeas was soaked to feed it in the morning. To the family, it wasn’t just another renegade parrot that had escaped from someone’s home; they considered it a godsend. Wearied by its harrowing experiences and the day-long starvation, the bird had grown quiet and sickly. It sat still, its head drooping because of the fatigue. Everyone feared that the wounded parrot was slowly dying.

A while later, Muravvat’s wife dragged a bed into the courtyard. Although Badi Bi and her grandkids were quick to lie down, no one really slept. They stayed awake till late, their eyes fixated on the cage.

The next morning, the house was once again abuzz with excitement. Awoken by the parrot’s screech, Muravvat’s wife had run excitedly to the cage. Perhaps the bird was trying to mimic a song. “Parrot, speak. Say ‘Allah, Allah,’” she entreated, holding on to the cage.

The bird immediately sprung to action and trilled. “Say, parrot; say ‘Sita Ram’. Bring me Shiva’s swig.”

“Haye Allah!” exclaimed Muravvat’s wife, visibly shocked. She released her hold on the cage and took a step back, as if recoiling in horror at the sight of a snake.

“Ammi Jaan! Ammi Jaan!” she shrieked.

Alarmed at the noise, Badi Bi and the kids woke up. “What happened? Is the bird dead already?”

Muravvat’s wife dashed towards the bed. “Ammi Jan, this parrot is Hindu. What to do? Should we set it free?”

“So what? Don’t release it,” the kids protested fervently. But Badi Bi suddenly seemed unmindful; she was lost in deep thought. She, too, had once tended to a Hindu parrot. She thought of the time she had eloped with Raghunath Misir, severing ties with her entire world — parents, relatives, community, village and her home — leaving all of it behind. Rechristening Raghunath Misir as Rahmat Miyan, she had devoted her entire life tending to him, just as one tends to a pet parrot. The runaways had settled in a new place and lived a life of obscurity,distant from the people they once called their own. Like a devout Muslim, Rahmat Miyan used to pray five times a day. He was well-regarded in the community. Over the years, he had made a fortune as a doctor of homoeopathy. He had built a house, educated Muravvat Hussain, his only son, and made him capable of leading a respectable life before peacefully exiting the world. No one other than Badi Bi knew his story. But, sometimes, Badi Bi suspected that her son had caught a whiff of their secret. Only Allah can tell if my suspicion is right.

Rahmat Miyan’s last day flashed before Badi Bi’s eyes. He had asked everyone to leave and had spoken to her in private. “Biwi, till this day, I have asked no favours of you. But today, I beg you for something. Won’t you oblige?”

Tears had rolled down her cheeks. She could merely nod in agreement.

“There is a bottle with sacred Ganga water in my trunk. Before I die, please pour a little of that in my mouth,” Rahmat had urged.

When Rahmat Miyan had eloped with Badi Bi, he had first taken her to Haridwar. She had vivid memories of that trip: she remembered how he had bathed in the Ganga, discarded his holy thread in the stream and filled a bottle with the river water. When Badi Bi had sought an explanation, he had promised to do so at an opportune moment. True to his promise, he had clarified it all when the time came. That day, Badi Bi had poured a spoonful of the Ganga water in his mouth, making certain no one saw her. She also recalled that Muravvat, too — knowingly or unknowingly — had poured a little water into his father’s mouth from the same bottle. At the time of his death, Rahmat had softly chanted “Hey Ram, Hey Ram.” How could she ever forget that!

One day, while rummaging through Rahmat Miyan’s trunk for a paper, Muravvat had stumbled upon an old photo. It was the portrait of a tonsured boy in his loincloth. He was wearing padukas and held a bamboo stick over his houlders, tiny bundles tied at both ends. Muravvat had stared at it for a while and then offered his pranam with folded hands before returning it safely to the trunk. Since that day, as far as Badi Bi knew, Muravvat had never felt the need to open the trunk.

“Of all the homes here, the wretch decides to come to ours. I’ll release it at once,” averred Muravvat’s wife.

By now Badi Bi had composed herself. “No, bahu. I will not have it chased away; if it has come to us, it will stay with us,” said Badi Bi, her voice firm.

She spoke with such conviction that Muravvat’s wife did not have the courage to defy her. Instead, Badi Bi turned to Muravvat and said, “Muravvat, yesterday it was put in that profane egg basket. Take it to the Ganga for a holy dip.”

The story was translated from the Bhojpuri by Gautam Chaubey.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading