Interview: Aanchal Malhotra, author, In the Language of Remembering

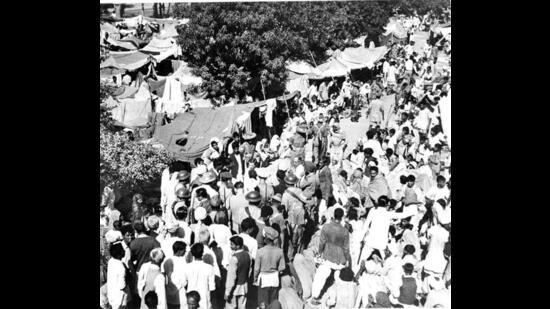

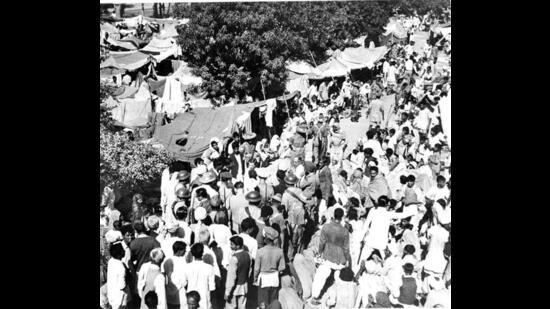

Ashis Nandy had written in the foreword of a book of Partition stories several years ago that “An unexamined past has to be lived out over succeeding generations”. In India, for decades after Partition, most of the country averted its gaze from the horrors of 1947; they had not suffered. Only some Punjabis and a few Bengalis, rare ones, broke the overwhelming silence that shrouded the story of their holocaust. By and large, even the very people who had suffered Partition’s worst effects, its scarred survivors, spoke little about it – so little that in many cases, their own children and grandchildren barely knew what had befallen the family elders in that time of historic turmoil when the British Indian Empire split into fragments. Few of the children and grandchildren bothered to ask. Aanchal Malhotra, author of two books of oral history on Partition, is one who did. Her latest work, In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition, is a tome of close to 700 pages documenting the Partition memories of her own family members, and of around 125 other people from different regions of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Do you find, I asked Aanchal, this unexamined past affecting our present politics?

“I am wary of associating everything to Partition. I don’t think you can possibly blame everything on one event or one origin” she replies. There are however certain things that she does connect with Partition. “When you tell an Indian Muslim, ‘Go to Pakistan’, that is prejudice that has originated or remained from that time. I think Partition is in the undercurrent of our politics. Unfortunately, it is being wielded almost to justify the two-nation theory” she says. She marvels at the overt hatred for the ‘other’ that is so evident now. “Why is it that the generations after Partition are far more small-minded than the generation that lived through Partition? Why do they not have that kind of obvious hate?” she asks. “I don’t want to say all, because some certainly do, depending on their circumstances, but in general it is a very uncommon thing for them to be overtly spewing hate, whereas the generations that haven’t lived through Partition do it quite comfortably”.

Considering how much of the Partition story was and is about hate, anger and violence, there is relatively little of these sentiments in her book. Though the book’s chapters are organised by emotion – such as fear, grief, hope and love – there is no chapter on anger or violence. “I was very conscious to not have those two chapters. Violence appears as a secondary character in almost every story”, she says. “It is understood that there may be violence in almost every story”. The anger, she contends, has cooled over time. “I don’t know if anger remains as lucid as it is passed down because we have distance from the event of Partition. Everyone was willing to reason and critically think about it”.

They were also willing to speak about it – a change from the decades of silence. She has a chapter on that silence in her book. Ironically, but unsurprisingly, it is a short chapter because of, well, the silence. It is odd that so many Partition survivors chose to not speak about what was perhaps the most significant event in their lives. Why?

“We can only speculate about the reasons for the silence”, she says. “If I look at my own family, one of them was that there was just no reason to talk about what had happened. My grandfather, I remember the first time I spoke to him he was really quite taken aback that I wanted to go back again and again to the time he lived in a camp, the time he was a refugee, because he had worked so hard to eradicate the notion of being a refugee by sort of overcompensating and making something of himself.”

But there are other instances, she adds. She mentions one of her interviewees, who is also an author. “I have this chapter here… Dr Kamra, in the foreword of her book…her father has written this, which is interesting because she told me she has never spoken to her father about Partition. He has written, ‘I feel privileged at this opportunity given by my daughter to speak, because I am one of the Silent Generation…silent because no one seemed to care, and silent because we were so busy restructuring our destroyed future.’ This puts the onus on two different generations. So maybe there are a myriad of reasons for silence, but I know that it renders people that don’t know anything about their families feeling very incapacitated”, she says.

In the course of her research, she came across people who have no knowledge about their family roots. “I don’t know if there’s a pattern to it but they are mostly families that are immigrant families overseas”, says Malhotra. “Two are in the UK, one is in America, one is in Canada. Maybe there’s an interesting observation there, on what life immigrant families choose to pursue, which memories they choose to leave behind”. The interview that really struck her was one with a woman named Jasmine. “I asked her, where are your grandparents from? She said ‘I don’t know’. When did they come? ‘I don’t know’. Where did they go to? ‘I don’t know’. What more can you ask someone? She said ‘I feel cheated that no one knew anything, that my mother couldn’t tell me anything’. There’s no space for her to go to find out any of the pieces, and there are tons of people like her in the world. There was nothing I could do to help her”.

She was, however, able to help others find out a bit more about their origins. “Two siblings I spoke to, Chhaya and Bharat, didn’t know anything about where their last name was from, and I remember being on a video call with them and showing them this glossary of Punjabi chiefs and tribes, and we found everything, where they were from…it was very surreal to I suppose give someone their history on a video call”, she says.

Empathy and compassion for the individual human beings across communities whose lives, even two generations on, were somehow affected by the maelstrom of Partition, runs through her work. “When I read books about Partition, they almost render the individual absent” she says. “There is no specificity of the individual. For instance, in our CBSE history books, they rendered the individual invisible…their specific losses, or what they felt, or how they rebuilt their lives, this was absent. With a lot of official archival history this is the problem, that it doesn’t consider the individual who was actually displaced”.

The absence of the ordinary human being from the larger narrative perhaps dehumanizes it, reducing messy complexities into neat binaries.

“When I was growing up, the way I understood it was very black and white”, says Malhotra. “Mind you I didn’t really learn of this at home, I learnt about it in school, and the way we were taught as part of our CBSE was that this happened and Pakistan was created and there was migration. But an event of this magnitude, so colossal in its consequences…there has to be more. Only when you speak to people do you find out that multi-dimensionality, whether it is in religion or in the complexities within religion, whether it is people of certain divisions staying back in the land that they were not supposed to stay back in, or people going back and forth, or basically just keeping ties to the other side”.

She has a story about someone who kept going back and forth to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, until 30 years after Partition. Given the breadth of her interviews, with people from across what used to be British India, I was curious to know about what characteristic differences she found across geographies in the memories of Partition. It was interesting as a researcher to compare the differences in the kind and volume of migration, and the violence, between the eastern and western flanks of India, she replied. She was also struck by the enduring porosity of the borders in the east.

There are also differences in the inherited memories of Partition between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. “Pakistanis have been raised with the two-nation theory. It is something that they encounter on an everyday basis or frequently enough, which as Indians we can ignore if we want to ignore it, so while the dominant narrative there is a political narrative of creation of a nation-state, the narrative in India often becomes one of longing, and longing sometimes falls into the trope of nostalgia”, says Aanchal. “In the case of Bangladesh there were hardly any stories from ’47, and if there are, the details are very scant”. Memory, for Bangladeshis, typically starts with the war of liberation they and their Indian allies fought against Pakistan in 1971 that made them an independent country.

The history of Partition, despite the plenitude of written documents and the relative recency of the event, remains contested. There are still political debates, with relevance to the present, about the roles of different organisations and individuals in causing it to happen. Human memory by its very nature is more fluid than history. It is also more personal, and hence more deeply felt.

“One of the things you can do with a book like this is show people the multiplicity of versions of memory that begin from the same event”, says Malhotra.

The Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie had spoken eloquently about the dangers of a single story. The task of documenting the multiple stories of Partition in our inherited memories is, perhaps, a necessary prelude to an examination of South Asia’s unexamined past. The single story rendered impossible connection between her American hostel roommate and her as human equals, Adichie had said.

It also militates against connection as human equals between Hindus and Muslims, and between Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.

Samrat Choudhury is an author and journalist, and Executive Editor of Partition Studies Quarterly

Ashis Nandy had written in the foreword of a book of Partition stories several years ago that “An unexamined past has to be lived out over succeeding generations”. In India, for decades after Partition, most of the country averted its gaze from the horrors of 1947; they had not suffered. Only some Punjabis and a few Bengalis, rare ones, broke the overwhelming silence that shrouded the story of their holocaust. By and large, even the very people who had suffered Partition’s worst effects, its scarred survivors, spoke little about it – so little that in many cases, their own children and grandchildren barely knew what had befallen the family elders in that time of historic turmoil when the British Indian Empire split into fragments. Few of the children and grandchildren bothered to ask. Aanchal Malhotra, author of two books of oral history on Partition, is one who did. Her latest work, In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition, is a tome of close to 700 pages documenting the Partition memories of her own family members, and of around 125 other people from different regions of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Do you find, I asked Aanchal, this unexamined past affecting our present politics?

“I am wary of associating everything to Partition. I don’t think you can possibly blame everything on one event or one origin” she replies. There are however certain things that she does connect with Partition. “When you tell an Indian Muslim, ‘Go to Pakistan’, that is prejudice that has originated or remained from that time. I think Partition is in the undercurrent of our politics. Unfortunately, it is being wielded almost to justify the two-nation theory” she says. She marvels at the overt hatred for the ‘other’ that is so evident now. “Why is it that the generations after Partition are far more small-minded than the generation that lived through Partition? Why do they not have that kind of obvious hate?” she asks. “I don’t want to say all, because some certainly do, depending on their circumstances, but in general it is a very uncommon thing for them to be overtly spewing hate, whereas the generations that haven’t lived through Partition do it quite comfortably”.

Considering how much of the Partition story was and is about hate, anger and violence, there is relatively little of these sentiments in her book. Though the book’s chapters are organised by emotion – such as fear, grief, hope and love – there is no chapter on anger or violence. “I was very conscious to not have those two chapters. Violence appears as a secondary character in almost every story”, she says. “It is understood that there may be violence in almost every story”. The anger, she contends, has cooled over time. “I don’t know if anger remains as lucid as it is passed down because we have distance from the event of Partition. Everyone was willing to reason and critically think about it”.

They were also willing to speak about it – a change from the decades of silence. She has a chapter on that silence in her book. Ironically, but unsurprisingly, it is a short chapter because of, well, the silence. It is odd that so many Partition survivors chose to not speak about what was perhaps the most significant event in their lives. Why?

“We can only speculate about the reasons for the silence”, she says. “If I look at my own family, one of them was that there was just no reason to talk about what had happened. My grandfather, I remember the first time I spoke to him he was really quite taken aback that I wanted to go back again and again to the time he lived in a camp, the time he was a refugee, because he had worked so hard to eradicate the notion of being a refugee by sort of overcompensating and making something of himself.”

But there are other instances, she adds. She mentions one of her interviewees, who is also an author. “I have this chapter here… Dr Kamra, in the foreword of her book…her father has written this, which is interesting because she told me she has never spoken to her father about Partition. He has written, ‘I feel privileged at this opportunity given by my daughter to speak, because I am one of the Silent Generation…silent because no one seemed to care, and silent because we were so busy restructuring our destroyed future.’ This puts the onus on two different generations. So maybe there are a myriad of reasons for silence, but I know that it renders people that don’t know anything about their families feeling very incapacitated”, she says.

In the course of her research, she came across people who have no knowledge about their family roots. “I don’t know if there’s a pattern to it but they are mostly families that are immigrant families overseas”, says Malhotra. “Two are in the UK, one is in America, one is in Canada. Maybe there’s an interesting observation there, on what life immigrant families choose to pursue, which memories they choose to leave behind”. The interview that really struck her was one with a woman named Jasmine. “I asked her, where are your grandparents from? She said ‘I don’t know’. When did they come? ‘I don’t know’. Where did they go to? ‘I don’t know’. What more can you ask someone? She said ‘I feel cheated that no one knew anything, that my mother couldn’t tell me anything’. There’s no space for her to go to find out any of the pieces, and there are tons of people like her in the world. There was nothing I could do to help her”.

She was, however, able to help others find out a bit more about their origins. “Two siblings I spoke to, Chhaya and Bharat, didn’t know anything about where their last name was from, and I remember being on a video call with them and showing them this glossary of Punjabi chiefs and tribes, and we found everything, where they were from…it was very surreal to I suppose give someone their history on a video call”, she says.

Empathy and compassion for the individual human beings across communities whose lives, even two generations on, were somehow affected by the maelstrom of Partition, runs through her work. “When I read books about Partition, they almost render the individual absent” she says. “There is no specificity of the individual. For instance, in our CBSE history books, they rendered the individual invisible…their specific losses, or what they felt, or how they rebuilt their lives, this was absent. With a lot of official archival history this is the problem, that it doesn’t consider the individual who was actually displaced”.

The absence of the ordinary human being from the larger narrative perhaps dehumanizes it, reducing messy complexities into neat binaries.

“When I was growing up, the way I understood it was very black and white”, says Malhotra. “Mind you I didn’t really learn of this at home, I learnt about it in school, and the way we were taught as part of our CBSE was that this happened and Pakistan was created and there was migration. But an event of this magnitude, so colossal in its consequences…there has to be more. Only when you speak to people do you find out that multi-dimensionality, whether it is in religion or in the complexities within religion, whether it is people of certain divisions staying back in the land that they were not supposed to stay back in, or people going back and forth, or basically just keeping ties to the other side”.

She has a story about someone who kept going back and forth to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, until 30 years after Partition. Given the breadth of her interviews, with people from across what used to be British India, I was curious to know about what characteristic differences she found across geographies in the memories of Partition. It was interesting as a researcher to compare the differences in the kind and volume of migration, and the violence, between the eastern and western flanks of India, she replied. She was also struck by the enduring porosity of the borders in the east.

There are also differences in the inherited memories of Partition between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. “Pakistanis have been raised with the two-nation theory. It is something that they encounter on an everyday basis or frequently enough, which as Indians we can ignore if we want to ignore it, so while the dominant narrative there is a political narrative of creation of a nation-state, the narrative in India often becomes one of longing, and longing sometimes falls into the trope of nostalgia”, says Aanchal. “In the case of Bangladesh there were hardly any stories from ’47, and if there are, the details are very scant”. Memory, for Bangladeshis, typically starts with the war of liberation they and their Indian allies fought against Pakistan in 1971 that made them an independent country.

The history of Partition, despite the plenitude of written documents and the relative recency of the event, remains contested. There are still political debates, with relevance to the present, about the roles of different organisations and individuals in causing it to happen. Human memory by its very nature is more fluid than history. It is also more personal, and hence more deeply felt.

“One of the things you can do with a book like this is show people the multiplicity of versions of memory that begin from the same event”, says Malhotra.

The Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie had spoken eloquently about the dangers of a single story. The task of documenting the multiple stories of Partition in our inherited memories is, perhaps, a necessary prelude to an examination of South Asia’s unexamined past. The single story rendered impossible connection between her American hostel roommate and her as human equals, Adichie had said.

It also militates against connection as human equals between Hindus and Muslims, and between Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.

Samrat Choudhury is an author and journalist, and Executive Editor of Partition Studies Quarterly