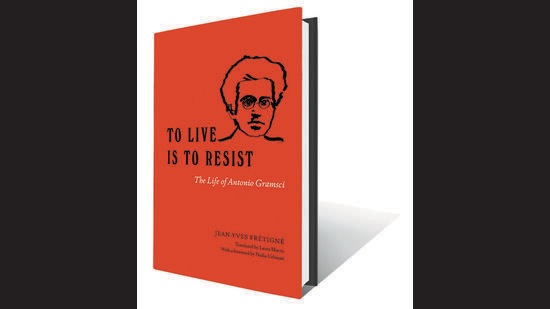

Review: To Live Is to Resist; The Life of Antonio Gramsci by Jean-Yves Frétigné

French historian Jean-Yves Frétigné’s biography of Antonio Gramsci, Vivre, c’est resister was published in 2017 in the 50th anniversary year of John M Cammett’s seminal work, Antonio Gramsci and the Origins of Italian Communism. Cammett was the father of Gramsci studies outside Italy. To Live Is to Resist: The Life of Antonio Gramsci is the book’s English version translated by Laura Marris. This latest biography opens a new window on Gramsci studies, which had already become a PhD industry by the mid-1970s. With an incisive 24-page foreword by Nadia Urbinati and a 20-page epilogue, this 328-page book unbundles a hitherto-undiscussed Gramsci to serious readers.

Urbinati writes that Gramsci was the “heir of Italian humanism, whose main reference points resided in the early Renaissance”; he was one who envisaged a path to social transformation in politics that would rely neither on a subjective will nor on an objective social science. “…no word can better express the nexus of Gramsci’s personal and political life than ‘prison.’ His ‘second prison was his body’ Prisons were the sources of his most seminal political categories — subalternity and hegemony,” she says adding that he “never fatalistically accepted his condition, and the spirit of rebellion was the blessing that saved him”.

On 8 November, 1926 when Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini got him arrested him from his home at 25 Via Morgagni in Rome at 10.30pm, Gramsci realised instantly that despite being an MP, the rest of his life would be spent in prison. He was sentenced to 20 years in jail. Every day for 122 months, he “forced himself to do the same things. Every morning, he woke up at the same time, exercised at the same time, fed a bird that visited him every day at the same time. He tried to eat at the same time, read at the same time, a self-imposed routine” in an attempt to resist prison. It was a lesson of rebellion in “an extreme condition of captivity”. It provided the setting for writing his Prison Notebooks that run into 3000-plus pages.

The prisons of fascist Europe became the greatest university system on the planet and Gramsci metamorphosed from operative to theorist even as he set about teaching courses on history and literature to inmates. “The fascists reserved special treatment for me and, from the revolutionary viewpoint, I therefore got off to an unsuccessful start. Because my voice does not carry, they gathered around me in order to hear me, and they let me say what I wanted, interrupting me only in order to drive me off the point, but with no attempt at sabotage,” he wrote to Julia Schucht, mother of his sons Delio and Giuliano.

Mussolini, whom Gramsci knew when both were with the Partito Socialista Italiano, referred to him in 1921 as “this Sardinian hunchback and professor of economics and philosophy” who had “an unquestionably powerful brain.” Five years later, the public prosecutor told the court – “We must stop this brain from functioning”. Protracted incarceration might have ended Gramsci’s life on 27 April 1937 but his cerebral potential for emancipation remains vibrant.

Though it was Romain Rolland who created the maxim “Pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will”, it was Gramsci who expanded on it even as he theorised concepts like “hegemony”, “passive revolution”, “historical bloc”, “subaltern”, “national-popular,” and “organic intellectuals” – all terms that have been debated extensively and will continue to be discussed. He used the word “hegemony” as part of the project to liberate the minds of subalterns. Lenin, in whom Gramsci found a mentor, was confused about hegemony.

Born in Ales on January 22, 1891 into a family of small-time “elites, at the mercy of fate” Gramsci’s grand father Gennaro Gramsci was a police colonel in the Neapolitan Army, who retained his rank after Italian unification. Frétigné demolishes “a pious legend that his parents were poor peasants” which was mistakenly articulated even by Gramsci’s closest comrade-in-arms in the Partito Comunista Italiano, PalmiroTogliatti in the first commemorative article on him in 1937. Nonetheless, the Gramscis did not have a comfortable existence. The family was driven to penury after his father was “imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy”. As a result, his mother had to make a living mending clothes. The young Antonio therefore confronted a tough life right from his childhood. This was in addition to his physical deformity, a hunched back caused by “a bad fall he’d taken after being dropped by a young woman from the village who sometimes came to help with the household tasks”. In 1933, following a collapse in his cell, attending physician Professor Umberto Arcangeli diagnosed that he suffered from a rare form of spinal tuberculosis.

Frétigné’s work covers the entire trajectory of Gramsci’s life from his childhood, his journalism, involvement in the workers’ movement, transition from social democrat to Marxist (from PSI to PCd’I), and his struggle in the PCd’I and the Communist International. Gramsci and Amadeo Bordiga, co-founder of PCd’I (along with Togliatti), had arrived in Moscow on 26 May 1922, the day Lenin suffered his first brain haemorrhage after a bullet lodged deep in his shoulder was removed. Gramsci and Bordiga fell apart in May 1924 when the latter sided with Leon Trotsky while Gramsci fully aligned himself with the Comintern (read Stalin), which expelled Trotsky. The Gramsci-Bordiga divide remained unresolved, Frétigné’s inclination towards Gramsci notwithstanding.

Gramsci fell in love with Julia, a violinist and member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour (Bolshevik) at a sanatorium in Moscow. His first son Delio was just two years old when he was imprisoned. His second son Giulani was born when he was in jail. Gramsci’s last letters were mainly addressed to his two sons and to his wife Julia, whom he never really understood.

Frétigné writes that the camaraderie between Gramsci and Pierre Straffa, a ‘Ricardian specialist’ and one of the best economists of his time, played a decisive role in inspiring him to write the Prison Notebooks. A professor in economics at the University of Cagliari by the age of 28, Straffa soon moved to England as he was “under surveillance from the regime” for his anti-Fascist stance and his critique of the Italian banking system. Gramsci believed Sraffa was “one of the intellectuals who could reinforce” the PCd’I’s foundations in its fight against Fascism. “There would be no anti-Fascist revolution so long as the workers were thinking of saving their jobs and their salaries to feed their families,” said Straffa. Incidentally, Gramsci’s youngest sister-in-law Tatiana and Straffa grew close while Gramsci was in prison. Frétigné dubs them “Comrade Straffa and Antigone”. All this was happening at a time when the Comintern was not keen on the release of Gramsci through an exchange of prisoners with Italy during the days when Stalin and Hitler were on good terms. So Romain Rolland’s article Pour ceux qui meurent dans les prisons de Mussolini: Antonio Gramsci (For Those Who Perish in Mussolini’s Prisons: Antonio Gramsci), published in Paris in September 1934, turned counterproductive.

Filled with fresh insights and information, Jean-Yves Frétigné’s work shows the contemporary reader why Antonio Gramsci’s ideas continue to be relevant.

Sankar Ray is a writer and commentator on Left politics and history, and environmental issues. He lives in Kolkata.

French historian Jean-Yves Frétigné’s biography of Antonio Gramsci, Vivre, c’est resister was published in 2017 in the 50th anniversary year of John M Cammett’s seminal work, Antonio Gramsci and the Origins of Italian Communism. Cammett was the father of Gramsci studies outside Italy. To Live Is to Resist: The Life of Antonio Gramsci is the book’s English version translated by Laura Marris. This latest biography opens a new window on Gramsci studies, which had already become a PhD industry by the mid-1970s. With an incisive 24-page foreword by Nadia Urbinati and a 20-page epilogue, this 328-page book unbundles a hitherto-undiscussed Gramsci to serious readers.

Urbinati writes that Gramsci was the “heir of Italian humanism, whose main reference points resided in the early Renaissance”; he was one who envisaged a path to social transformation in politics that would rely neither on a subjective will nor on an objective social science. “…no word can better express the nexus of Gramsci’s personal and political life than ‘prison.’ His ‘second prison was his body’ Prisons were the sources of his most seminal political categories — subalternity and hegemony,” she says adding that he “never fatalistically accepted his condition, and the spirit of rebellion was the blessing that saved him”.

On 8 November, 1926 when Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini got him arrested him from his home at 25 Via Morgagni in Rome at 10.30pm, Gramsci realised instantly that despite being an MP, the rest of his life would be spent in prison. He was sentenced to 20 years in jail. Every day for 122 months, he “forced himself to do the same things. Every morning, he woke up at the same time, exercised at the same time, fed a bird that visited him every day at the same time. He tried to eat at the same time, read at the same time, a self-imposed routine” in an attempt to resist prison. It was a lesson of rebellion in “an extreme condition of captivity”. It provided the setting for writing his Prison Notebooks that run into 3000-plus pages.

The prisons of fascist Europe became the greatest university system on the planet and Gramsci metamorphosed from operative to theorist even as he set about teaching courses on history and literature to inmates. “The fascists reserved special treatment for me and, from the revolutionary viewpoint, I therefore got off to an unsuccessful start. Because my voice does not carry, they gathered around me in order to hear me, and they let me say what I wanted, interrupting me only in order to drive me off the point, but with no attempt at sabotage,” he wrote to Julia Schucht, mother of his sons Delio and Giuliano.

Mussolini, whom Gramsci knew when both were with the Partito Socialista Italiano, referred to him in 1921 as “this Sardinian hunchback and professor of economics and philosophy” who had “an unquestionably powerful brain.” Five years later, the public prosecutor told the court – “We must stop this brain from functioning”. Protracted incarceration might have ended Gramsci’s life on 27 April 1937 but his cerebral potential for emancipation remains vibrant.

Though it was Romain Rolland who created the maxim “Pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will”, it was Gramsci who expanded on it even as he theorised concepts like “hegemony”, “passive revolution”, “historical bloc”, “subaltern”, “national-popular,” and “organic intellectuals” – all terms that have been debated extensively and will continue to be discussed. He used the word “hegemony” as part of the project to liberate the minds of subalterns. Lenin, in whom Gramsci found a mentor, was confused about hegemony.

Born in Ales on January 22, 1891 into a family of small-time “elites, at the mercy of fate” Gramsci’s grand father Gennaro Gramsci was a police colonel in the Neapolitan Army, who retained his rank after Italian unification. Frétigné demolishes “a pious legend that his parents were poor peasants” which was mistakenly articulated even by Gramsci’s closest comrade-in-arms in the Partito Comunista Italiano, PalmiroTogliatti in the first commemorative article on him in 1937. Nonetheless, the Gramscis did not have a comfortable existence. The family was driven to penury after his father was “imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy”. As a result, his mother had to make a living mending clothes. The young Antonio therefore confronted a tough life right from his childhood. This was in addition to his physical deformity, a hunched back caused by “a bad fall he’d taken after being dropped by a young woman from the village who sometimes came to help with the household tasks”. In 1933, following a collapse in his cell, attending physician Professor Umberto Arcangeli diagnosed that he suffered from a rare form of spinal tuberculosis.

Frétigné’s work covers the entire trajectory of Gramsci’s life from his childhood, his journalism, involvement in the workers’ movement, transition from social democrat to Marxist (from PSI to PCd’I), and his struggle in the PCd’I and the Communist International. Gramsci and Amadeo Bordiga, co-founder of PCd’I (along with Togliatti), had arrived in Moscow on 26 May 1922, the day Lenin suffered his first brain haemorrhage after a bullet lodged deep in his shoulder was removed. Gramsci and Bordiga fell apart in May 1924 when the latter sided with Leon Trotsky while Gramsci fully aligned himself with the Comintern (read Stalin), which expelled Trotsky. The Gramsci-Bordiga divide remained unresolved, Frétigné’s inclination towards Gramsci notwithstanding.

Gramsci fell in love with Julia, a violinist and member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour (Bolshevik) at a sanatorium in Moscow. His first son Delio was just two years old when he was imprisoned. His second son Giulani was born when he was in jail. Gramsci’s last letters were mainly addressed to his two sons and to his wife Julia, whom he never really understood.

Frétigné writes that the camaraderie between Gramsci and Pierre Straffa, a ‘Ricardian specialist’ and one of the best economists of his time, played a decisive role in inspiring him to write the Prison Notebooks. A professor in economics at the University of Cagliari by the age of 28, Straffa soon moved to England as he was “under surveillance from the regime” for his anti-Fascist stance and his critique of the Italian banking system. Gramsci believed Sraffa was “one of the intellectuals who could reinforce” the PCd’I’s foundations in its fight against Fascism. “There would be no anti-Fascist revolution so long as the workers were thinking of saving their jobs and their salaries to feed their families,” said Straffa. Incidentally, Gramsci’s youngest sister-in-law Tatiana and Straffa grew close while Gramsci was in prison. Frétigné dubs them “Comrade Straffa and Antigone”. All this was happening at a time when the Comintern was not keen on the release of Gramsci through an exchange of prisoners with Italy during the days when Stalin and Hitler were on good terms. So Romain Rolland’s article Pour ceux qui meurent dans les prisons de Mussolini: Antonio Gramsci (For Those Who Perish in Mussolini’s Prisons: Antonio Gramsci), published in Paris in September 1934, turned counterproductive.

Filled with fresh insights and information, Jean-Yves Frétigné’s work shows the contemporary reader why Antonio Gramsci’s ideas continue to be relevant.

Sankar Ray is a writer and commentator on Left politics and history, and environmental issues. He lives in Kolkata.