Tom Girardi gave millions to Democrats. Was the money stolen?

Gavin. Eric. Barack. Jerry. Dianne. Hillary. Joe.

When it came to Democratic politicians, Tom Girardi called them by their first names and their campaigns called him for money.

The Los Angeles legal legend was a major party donor for decades, a self-described “limousine liberal” who bragged about the influence his money bought him in the selection of judges. He poured millions into local, state and national races personally and lined up additional donations from his wife, “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika; the employees of his law firm; and the multitude of California trial lawyers who did business with him — or hoped to.

Girardi kept throwing splashy fundraisers and writing big checks even as his financial situation grew dire. In the last decade, he defaulted on a series of high-interest loans and was forced to liquidate his stock portfolio yet he and his wife still doled out more than $2 million to the national Democratic Party and individual candidates, election filings show.

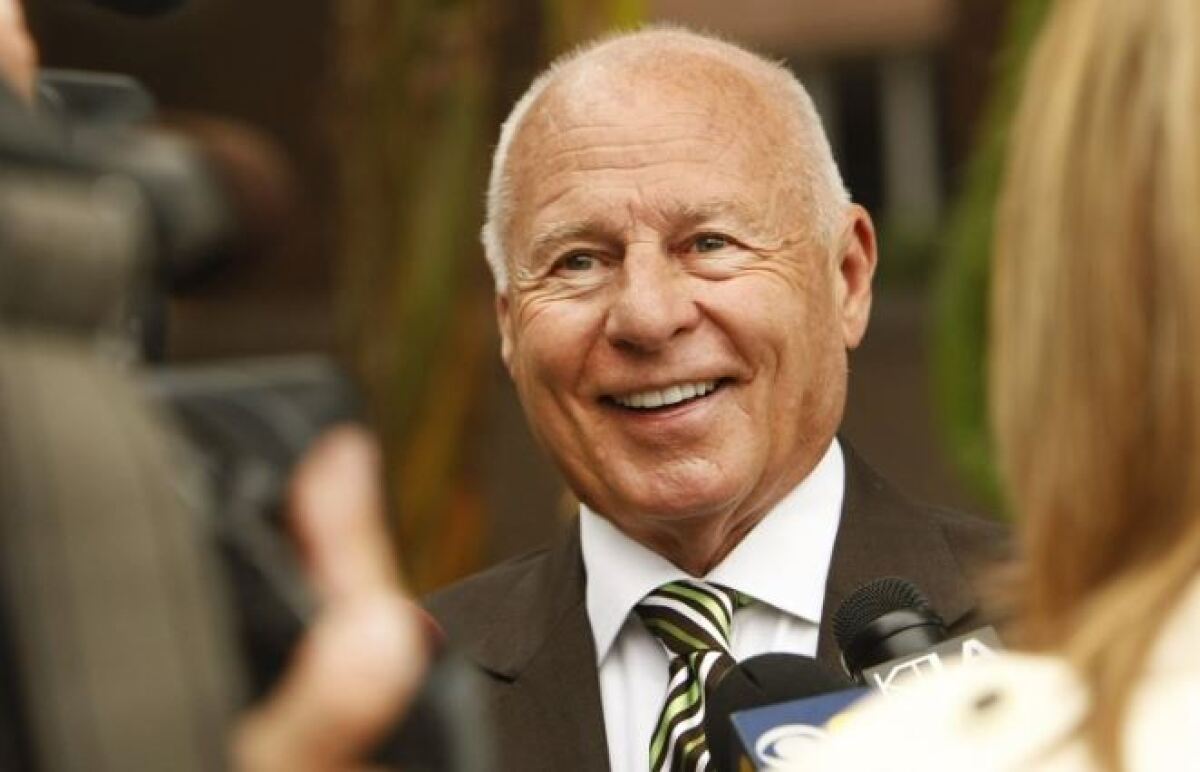

Tom Girardi.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Those receiving funds included presidential contenders Joe Biden ($11,200), Barack Obama ($62,500) and Hillary Clinton ($60,400), Gov. Gavin Newsom ($66,900), U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein ($18,700), former state Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones ($37,244), L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti ($9,500) and City Atty. Mike Feuer ($11,000).

How did a deeply indebted lawyer obtain money to shower on candidates and campaigns? No ready explanation has surfaced. But a Times review of contributions and law firm financial records raises questions about whether Girardi used clients’ funds to make the donations.

In the years that he and his wife gave $2 million to candidates, Girardi treated a bank account meant to safeguard settlement money for clients as “his personal piggy bank… to support his lavish lifestyle,” according to a recent filing by the trustee overseeing the bankruptcy of his law firm, Girardi Keese. In that same time frame, the trustee wrote, Girardi “stole at least $14,000,000 in settlement funds that should have gone to the Firm’s clients.”

Those clients were mainly of modest means and already suffering from health problems because of toxic contamination, recalled pharmaceuticals, motor vehicle crashes or other misfortunes. Many are still trying to collect their full settlements, according to bankruptcy claims they have filed seeking compensation.

Former client Christina Fulton, who was seriously injured in a car accident and contends Girardi embezzled about $745,000 from her settlement, called on politicians to reevaluate accepting the donations.

“I think it’s their responsibility to turn around and look at this and say, ‘Whose money is this? Whose money really is this?’” Fulton said.

The Times could find no evidence any of the campaigns had returned the donations since Girardi became a pariah after the collapse of his storied firm nearly two years ago. Most candidates contacted by The Times did not respond to questions.

A spokesperson for Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) said last year her campaign flagged a $5,400 donation she had received from Girardi in 2017 and placed the money in a “segregated fund” that would eventually go to benefit victims.

After being contacted by The Times, U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) said he would donate $2,000 Girardi gave him in 2014 to legal services for the poor.

Feuer, the city attorney, said through a spokesman that the accounts that received Girardi donations no longer existed.

“It is not possible to return or re-direct donations from a closed account,” said spokesman Rob Wilcox. He added that “during the period in which these contributions were made, the revelations regarding Mr. Girardi, who had supported a wide range of accomplished public officials, had not come to light.”

Girardi’s decision to continue funding candidates in the face of crushing financial problems offers additional evidence that he regarded political connections as central to maintaining his facade.

As he brushed aside pleas for money from clients including a burn victim, residents of polluted communities and young men injured by a pharmaceutical, he kept holding court with state and local candidates at the Jonathan Club and Morton’s steakhouse and sending checks to a roster of national Democrats that would have been right at home in an MSNBC greenroom.

Among them were U.S. Sens. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.), Tim Kaine (D-Va.), Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.); and California U.S. Reps. Eric Swalwell, Katie Hill and Katie Porter.

The subject of Girardi’s political giving has not come up in ongoing bankruptcy proceedings for Girardi Keese. But Elissa Miller, the court-appointed bankruptcy trustee, has said in court filings by her attorneys that she is looking into “numerous transfers” of firm assets to “third parties” as she attempts to track down money to compensate cheated clients and other creditors.

Diamond earrings Girardi apparently purchased for his wife with client money were ordered seized and auctioned off this year. Last month, his onetime mistress, retired appellate Justice Tricia Bigelow, returned jewelry and other gifts to the trustee. Among the presents Girardi gave her was $300,000 from a client bank account.

Experts in campaign finance law said politicians were not legally required to return the money unless they knew or should have known at the time of the donation that Girardi was using stolen funds. That appears an unlikely scenario given the sterling reputation Girardi enjoyed until his downfall.

Robert Stern, co-author of the state Political Reform Act of 1974, said that even if the checks were marked as coming from the client bank account, known as a trust account, “I’m not even sure that would have raised red flags for the clerks who were processing it because I’m not sure they would have known what a client trust account was.”

Ann Ravel, former chair of the state Fair Political Practices Commission, agreed that there was no legal requirement to return the funds, but said that regardless of the law, candidates who still had money in their campaign accounts should send it back.

“It should be a moral obligation honestly,” said Ravel, who was an Obama appointee to the Federal Election Commission. She said the point of election law is “to have ethical campaigns. That is what it is all about and you are not supposed to be getting stolen money.”

In other cases in which a high-profile donor fell into scandal, politicians have opted not to keep contributions. After Democratic donor Ed Buck was implicated in the fatal drug overdoses of two men at his West Hollywood condo, U.S. Reps. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) and Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles) donated money they got from Buck to charity, though others who had received more did not. Similarly, politicians including Sens. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) gave donations they had received from disgraced film mogul Harvey Weinstein to nonprofits benefiting domestic violence and rape victims.

“The money starts going back when it is too politically expensive to keep it,” said Jessica Levinson, former chair of the L.A. Ethics Commission.

Girardi was a donor of a different magnitude than Buck, whose contributions totaled about $500,000, or Weinstein, who along with his family contributed about $1.4 million. Available campaign records, which cover only a portion of lifetime political giving, show donations of more than $4 million from Girardi and his three wives.

People who raised money from Girardi or observed others who did said the lawyer’s generosity didn’t seem based in an interest in policy, but in a desire to cement his image as a power broker.

“It’s about the mystique of Girardi,” said Mike Madrid, a Republican strategist in Sacramento. “There’s not a return on investment in terms of cash on cash. … The return on investment is that Girardi becomes a bigger player in L.A. You have to go through [him].”

Girardi acknowledged his aim was self-interest in an unpublished memoir titled “May It Please the Court” in which he described himself as “a one-trick pony” in politics: “I don’t care what they do in Syria. I don’t care what the tax deal is. I don’t get worked up over gay marriage or immigration or global warming or any of that other stuff. I want my law firm to thrive.”

In his view, the health of his firm depended on strong relationships with the men and women who ruled on his cases and he started working on those relationships before the judges even put on their robes.

Beginning in the 1970s, when he developed a friendship with Gov. Jerry Brown, he positioned himself as a gatekeeper between aspiring judges in Southern California and governors who make appointments to the Superior, Appellate and Supreme court benches. He often recounted backroom meetings where he and other powerful lawyers met to decide which of their colleagues should be elevated to the bench.

“I make no bones about influencing judicial appointments. Awful, you say? Unethical? Well, who better to recommend a man to the bench than someone who works with him every day,” Girardi wrote in his memoir.

He described numerous dinner parties at his Pasadena home that ended with Brown surprising one of Girardi’s associates by swearing him in as a judge on the spot. A spokesman for Brown, Evan Westrup, said in an email that Girardi was “just one of hundreds who offered an opinion” on judicial candidates and the account of the Pasadena dinner parties was “replete with inaccuracies and falsehoods.”

His sway in the process continued through the governorship of Newsom, who named him in 2019 to a committee vetting judicial candidates in L.A.

“Ideally, politics should stay outside the courtroom, but in the real world politics are a fact of life,” Girardi wrote in his memoir.

Brown’s advisor on judicial appointments, Joshua Groban, and the man who held the same role in Newsom’s administration, Martin Jenkins, are both now justices on the state Supreme Court and did not respond to interview requests made through a court spokesman.

Girardi presented his interest in judicial candidates as part of an overall concern for the administration of the courts where he practiced, but since his downfall, it’s become clear that he had other motives for cultivating their goodwill.

He and his firm were sued more than a hundred times by disgruntled clients and colleagues for legal malpractice, breach of contract and other similar claims that most often played out in L.A. courthouses.

Nicholas Rowley, a plaintiff’s attorney with a national reputation, said that when he threatened to sue Girardi in 2004 for failing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees from joint cases, the older lawyer replied, “Go ahead and try.”

“I know every judge in L.A…. I got most of them appointed,” Rowley recalled Girardi saying.

After consulting with other lawyers, Rowley decided it was not in his interest to sue, he said. He and Girardi never again worked on cases together, but they occasionally co-hosted political fundraisers.

“If Tom called on you to be part of something or to give money, you didn’t say no because he had the ability and the power to make or break people,” he recalled.

When Rowley in 2019 spearheaded an ultimately successful effort to raise California’s $250,000 cap on medical malpractice awards — a thorn in the side of trial lawyers for five decades — he called Girardi for a donation. The lawyer refused.

“That wasn’t Tom’s gig,” Rowley said.

Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School, where Girardi was an alumnus and donor, said she doubted he saw a straight line between his political contributions and the appointment of judges who might look the other way on misuse of client funds.

“It’s not as narrow as, ‘I hope a judge I might be in front of will realize they shouldn’t screw with me,’” Levinson said. “It’s, ‘I hope everyone sees how powerful I am. Look who we have access to, look who comes to speak to us for lunch on a Thursday.’”

On visits to Girardi at his Wilshire Boulevard office, candidates seeking money took in walls of photos of him with powerful national politicians. He called the late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) a close friend and bragged about taking trips to spend time with the Clintons. Then-Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy spoke at the 2002 dedication of a Loyola Law School building named for Girardi’s father. When Biden was running for president in 2019, Girardi filled a dining room at the Jonathan Club with donors for a breakfast fundraiser.

The Girardis hosted fundraisers in L.A. in 2008 when North Carolina trial lawyer John Edwards announced his run for the presidency. In his memoir, Girardi recalled sharing “pipe dreams” with his wife, Erika, about a post in his administration.

“Maybe I’d do Counselor to the President or something like that,” he recalled musing to his wife. “But you’re not going to catch me doing anything that requires Senate confirmation. I’ve seen Senate confirmations. I don’t need some big Administration job that bad.”

After Edwards’ political career cratered, Girardi turned to another telegenic rising star in the Democratic Party, Newsom.

The son of a state appellate judge, Newsom was one of many politicians who appeared on Girardi’s weekly syndicated radio show “Champions of Justice.” In a broadcast, Newsom appeared to enjoy the praise Girardi heaped on his 2013 political manifesto “Citizenville,” which had recently been published.

“A lot of our mutual friends from President Clinton on down are big supporters of that book,” Newsom, then lieutenant governor, said at the time.

Newsom had the backing of the Getty family and other prominent Bay Area donors, but when invited on Bravo — home of “The Real Housewives” franchise — in 2016 he singled out Girardi’s largesse, calling him “one of the major donors in California politics.”

“Wow. And does he give to you?” asked Andy Cohen, host of the talk show “Watch What Happens Live.”

“He has been extraordinarily generous — so she is my favorite Real Housewife,” a grinning Newsom said of Erika Girardi.

Nathan Ballard, a former Newsom advisor and Democratic strategist, denied that the lawyer had any real clout with the governor: “Girardi was not in Gavin Newsom’s inner circle by any stretch.”

Ballard, who worked with Newsom for years, said he saw donors in the party who gave less than Girardi command more respect and attention because of their sustained and deep interest in its causes.

“He wasn’t really in that category,” Ballard said, “though you can’t deny he was a significant contributor.”

Bankruptcy records show the money Girardi misappropriated included a settlement due to Cody Thompson, a 31-year-old Indiana man with autism and the genetic disorder Fragile X syndrome. Girardi negotiated a $50,000 settlement for Thompson in 2019 with the manufacturer of a drug that caused side effects in many young autistic men, according to a bankruptcy claim.

Gisele Thompson-Fry, a single mother who provides round-the-clock care to her son, said the family hoped to use the settlement funds for a down payment on a home, but the check never came.

“We got zero,” she said.

Once a Republican, Thompson-Fry said she became “a big liberal” after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which allowed her to get cancer treatment: “I always tell people [Obama] saved my life.”

She said candidates who received donations from Girardi and his wife should use the money to help compensate cheated clients like her son.

“Because they are Democrats, they should,” she said. “We are the people that care about the underdog.”

Gavin. Eric. Barack. Jerry. Dianne. Hillary. Joe.

When it came to Democratic politicians, Tom Girardi called them by their first names and their campaigns called him for money.

The Los Angeles legal legend was a major party donor for decades, a self-described “limousine liberal” who bragged about the influence his money bought him in the selection of judges. He poured millions into local, state and national races personally and lined up additional donations from his wife, “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika; the employees of his law firm; and the multitude of California trial lawyers who did business with him — or hoped to.

Girardi kept throwing splashy fundraisers and writing big checks even as his financial situation grew dire. In the last decade, he defaulted on a series of high-interest loans and was forced to liquidate his stock portfolio yet he and his wife still doled out more than $2 million to the national Democratic Party and individual candidates, election filings show.

Tom Girardi.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Those receiving funds included presidential contenders Joe Biden ($11,200), Barack Obama ($62,500) and Hillary Clinton ($60,400), Gov. Gavin Newsom ($66,900), U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein ($18,700), former state Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones ($37,244), L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti ($9,500) and City Atty. Mike Feuer ($11,000).

How did a deeply indebted lawyer obtain money to shower on candidates and campaigns? No ready explanation has surfaced. But a Times review of contributions and law firm financial records raises questions about whether Girardi used clients’ funds to make the donations.

In the years that he and his wife gave $2 million to candidates, Girardi treated a bank account meant to safeguard settlement money for clients as “his personal piggy bank… to support his lavish lifestyle,” according to a recent filing by the trustee overseeing the bankruptcy of his law firm, Girardi Keese. In that same time frame, the trustee wrote, Girardi “stole at least $14,000,000 in settlement funds that should have gone to the Firm’s clients.”

Those clients were mainly of modest means and already suffering from health problems because of toxic contamination, recalled pharmaceuticals, motor vehicle crashes or other misfortunes. Many are still trying to collect their full settlements, according to bankruptcy claims they have filed seeking compensation.

Former client Christina Fulton, who was seriously injured in a car accident and contends Girardi embezzled about $745,000 from her settlement, called on politicians to reevaluate accepting the donations.

“I think it’s their responsibility to turn around and look at this and say, ‘Whose money is this? Whose money really is this?’” Fulton said.

The Times could find no evidence any of the campaigns had returned the donations since Girardi became a pariah after the collapse of his storied firm nearly two years ago. Most candidates contacted by The Times did not respond to questions.

A spokesperson for Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) said last year her campaign flagged a $5,400 donation she had received from Girardi in 2017 and placed the money in a “segregated fund” that would eventually go to benefit victims.

After being contacted by The Times, U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) said he would donate $2,000 Girardi gave him in 2014 to legal services for the poor.

Feuer, the city attorney, said through a spokesman that the accounts that received Girardi donations no longer existed.

“It is not possible to return or re-direct donations from a closed account,” said spokesman Rob Wilcox. He added that “during the period in which these contributions were made, the revelations regarding Mr. Girardi, who had supported a wide range of accomplished public officials, had not come to light.”

Girardi’s decision to continue funding candidates in the face of crushing financial problems offers additional evidence that he regarded political connections as central to maintaining his facade.

As he brushed aside pleas for money from clients including a burn victim, residents of polluted communities and young men injured by a pharmaceutical, he kept holding court with state and local candidates at the Jonathan Club and Morton’s steakhouse and sending checks to a roster of national Democrats that would have been right at home in an MSNBC greenroom.

Among them were U.S. Sens. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.), Tim Kaine (D-Va.), Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.); and California U.S. Reps. Eric Swalwell, Katie Hill and Katie Porter.

The subject of Girardi’s political giving has not come up in ongoing bankruptcy proceedings for Girardi Keese. But Elissa Miller, the court-appointed bankruptcy trustee, has said in court filings by her attorneys that she is looking into “numerous transfers” of firm assets to “third parties” as she attempts to track down money to compensate cheated clients and other creditors.

Diamond earrings Girardi apparently purchased for his wife with client money were ordered seized and auctioned off this year. Last month, his onetime mistress, retired appellate Justice Tricia Bigelow, returned jewelry and other gifts to the trustee. Among the presents Girardi gave her was $300,000 from a client bank account.

Experts in campaign finance law said politicians were not legally required to return the money unless they knew or should have known at the time of the donation that Girardi was using stolen funds. That appears an unlikely scenario given the sterling reputation Girardi enjoyed until his downfall.

Robert Stern, co-author of the state Political Reform Act of 1974, said that even if the checks were marked as coming from the client bank account, known as a trust account, “I’m not even sure that would have raised red flags for the clerks who were processing it because I’m not sure they would have known what a client trust account was.”

Ann Ravel, former chair of the state Fair Political Practices Commission, agreed that there was no legal requirement to return the funds, but said that regardless of the law, candidates who still had money in their campaign accounts should send it back.

“It should be a moral obligation honestly,” said Ravel, who was an Obama appointee to the Federal Election Commission. She said the point of election law is “to have ethical campaigns. That is what it is all about and you are not supposed to be getting stolen money.”

In other cases in which a high-profile donor fell into scandal, politicians have opted not to keep contributions. After Democratic donor Ed Buck was implicated in the fatal drug overdoses of two men at his West Hollywood condo, U.S. Reps. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) and Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles) donated money they got from Buck to charity, though others who had received more did not. Similarly, politicians including Sens. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) gave donations they had received from disgraced film mogul Harvey Weinstein to nonprofits benefiting domestic violence and rape victims.

“The money starts going back when it is too politically expensive to keep it,” said Jessica Levinson, former chair of the L.A. Ethics Commission.

Girardi was a donor of a different magnitude than Buck, whose contributions totaled about $500,000, or Weinstein, who along with his family contributed about $1.4 million. Available campaign records, which cover only a portion of lifetime political giving, show donations of more than $4 million from Girardi and his three wives.

People who raised money from Girardi or observed others who did said the lawyer’s generosity didn’t seem based in an interest in policy, but in a desire to cement his image as a power broker.

“It’s about the mystique of Girardi,” said Mike Madrid, a Republican strategist in Sacramento. “There’s not a return on investment in terms of cash on cash. … The return on investment is that Girardi becomes a bigger player in L.A. You have to go through [him].”

Girardi acknowledged his aim was self-interest in an unpublished memoir titled “May It Please the Court” in which he described himself as “a one-trick pony” in politics: “I don’t care what they do in Syria. I don’t care what the tax deal is. I don’t get worked up over gay marriage or immigration or global warming or any of that other stuff. I want my law firm to thrive.”

In his view, the health of his firm depended on strong relationships with the men and women who ruled on his cases and he started working on those relationships before the judges even put on their robes.

Beginning in the 1970s, when he developed a friendship with Gov. Jerry Brown, he positioned himself as a gatekeeper between aspiring judges in Southern California and governors who make appointments to the Superior, Appellate and Supreme court benches. He often recounted backroom meetings where he and other powerful lawyers met to decide which of their colleagues should be elevated to the bench.

“I make no bones about influencing judicial appointments. Awful, you say? Unethical? Well, who better to recommend a man to the bench than someone who works with him every day,” Girardi wrote in his memoir.

He described numerous dinner parties at his Pasadena home that ended with Brown surprising one of Girardi’s associates by swearing him in as a judge on the spot. A spokesman for Brown, Evan Westrup, said in an email that Girardi was “just one of hundreds who offered an opinion” on judicial candidates and the account of the Pasadena dinner parties was “replete with inaccuracies and falsehoods.”

His sway in the process continued through the governorship of Newsom, who named him in 2019 to a committee vetting judicial candidates in L.A.

“Ideally, politics should stay outside the courtroom, but in the real world politics are a fact of life,” Girardi wrote in his memoir.

Brown’s advisor on judicial appointments, Joshua Groban, and the man who held the same role in Newsom’s administration, Martin Jenkins, are both now justices on the state Supreme Court and did not respond to interview requests made through a court spokesman.

Girardi presented his interest in judicial candidates as part of an overall concern for the administration of the courts where he practiced, but since his downfall, it’s become clear that he had other motives for cultivating their goodwill.

He and his firm were sued more than a hundred times by disgruntled clients and colleagues for legal malpractice, breach of contract and other similar claims that most often played out in L.A. courthouses.

Nicholas Rowley, a plaintiff’s attorney with a national reputation, said that when he threatened to sue Girardi in 2004 for failing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees from joint cases, the older lawyer replied, “Go ahead and try.”

“I know every judge in L.A…. I got most of them appointed,” Rowley recalled Girardi saying.

After consulting with other lawyers, Rowley decided it was not in his interest to sue, he said. He and Girardi never again worked on cases together, but they occasionally co-hosted political fundraisers.

“If Tom called on you to be part of something or to give money, you didn’t say no because he had the ability and the power to make or break people,” he recalled.

When Rowley in 2019 spearheaded an ultimately successful effort to raise California’s $250,000 cap on medical malpractice awards — a thorn in the side of trial lawyers for five decades — he called Girardi for a donation. The lawyer refused.

“That wasn’t Tom’s gig,” Rowley said.

Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School, where Girardi was an alumnus and donor, said she doubted he saw a straight line between his political contributions and the appointment of judges who might look the other way on misuse of client funds.

“It’s not as narrow as, ‘I hope a judge I might be in front of will realize they shouldn’t screw with me,’” Levinson said. “It’s, ‘I hope everyone sees how powerful I am. Look who we have access to, look who comes to speak to us for lunch on a Thursday.’”

On visits to Girardi at his Wilshire Boulevard office, candidates seeking money took in walls of photos of him with powerful national politicians. He called the late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) a close friend and bragged about taking trips to spend time with the Clintons. Then-Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy spoke at the 2002 dedication of a Loyola Law School building named for Girardi’s father. When Biden was running for president in 2019, Girardi filled a dining room at the Jonathan Club with donors for a breakfast fundraiser.

The Girardis hosted fundraisers in L.A. in 2008 when North Carolina trial lawyer John Edwards announced his run for the presidency. In his memoir, Girardi recalled sharing “pipe dreams” with his wife, Erika, about a post in his administration.

“Maybe I’d do Counselor to the President or something like that,” he recalled musing to his wife. “But you’re not going to catch me doing anything that requires Senate confirmation. I’ve seen Senate confirmations. I don’t need some big Administration job that bad.”

After Edwards’ political career cratered, Girardi turned to another telegenic rising star in the Democratic Party, Newsom.

The son of a state appellate judge, Newsom was one of many politicians who appeared on Girardi’s weekly syndicated radio show “Champions of Justice.” In a broadcast, Newsom appeared to enjoy the praise Girardi heaped on his 2013 political manifesto “Citizenville,” which had recently been published.

“A lot of our mutual friends from President Clinton on down are big supporters of that book,” Newsom, then lieutenant governor, said at the time.

Newsom had the backing of the Getty family and other prominent Bay Area donors, but when invited on Bravo — home of “The Real Housewives” franchise — in 2016 he singled out Girardi’s largesse, calling him “one of the major donors in California politics.”

“Wow. And does he give to you?” asked Andy Cohen, host of the talk show “Watch What Happens Live.”

“He has been extraordinarily generous — so she is my favorite Real Housewife,” a grinning Newsom said of Erika Girardi.

Nathan Ballard, a former Newsom advisor and Democratic strategist, denied that the lawyer had any real clout with the governor: “Girardi was not in Gavin Newsom’s inner circle by any stretch.”

Ballard, who worked with Newsom for years, said he saw donors in the party who gave less than Girardi command more respect and attention because of their sustained and deep interest in its causes.

“He wasn’t really in that category,” Ballard said, “though you can’t deny he was a significant contributor.”

Bankruptcy records show the money Girardi misappropriated included a settlement due to Cody Thompson, a 31-year-old Indiana man with autism and the genetic disorder Fragile X syndrome. Girardi negotiated a $50,000 settlement for Thompson in 2019 with the manufacturer of a drug that caused side effects in many young autistic men, according to a bankruptcy claim.

Gisele Thompson-Fry, a single mother who provides round-the-clock care to her son, said the family hoped to use the settlement funds for a down payment on a home, but the check never came.

“We got zero,” she said.

Once a Republican, Thompson-Fry said she became “a big liberal” after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which allowed her to get cancer treatment: “I always tell people [Obama] saved my life.”

She said candidates who received donations from Girardi and his wife should use the money to help compensate cheated clients like her son.

“Because they are Democrats, they should,” she said. “We are the people that care about the underdog.”