A robot named Yomi put a new tooth in my head. It was great

The novocaine made the lower part of my face feel like a sack of wet cement. A faint tinny sound of muzak leaked into the room from somewhere above. A blue surgical drape rested over my face; the small white spot from the dentist’s headlamp danced over it then finally zeroed in on my mouth. I heard Dr. Mohamed Ali exchange some numbers—they sounded like fine coordinates—with an assistant bent over a laptop nearby. Then I heard the robot draw near and knew it was almost ready to begin its careful journey through my gum and down into my jawbone. Dr. Ali uttered a single word—“Guided”—and the drilling began.

Dr. Mohamed Ali was the first dentist in San Francisco to begin replacing missing teeth with the help of a robot called Yomi. The titanium implant he and Yomi installed in my jaw would eventually anchor a new (man-made) tooth to replace the one I’d lost after a failed root canal two years ago. Yomi’s purpose is to make implantation surgery a more exacting, and predictable, process for dentists. The system’s software develops a detailed spatial understanding of the patient’s mouth, then the robotic arm “guides” the dentist to the exact place, and angle, to drill. The 15-year-old healthtech company Neocis spent years building and refining Yomi, and then years more putting it through clinical trials to prove its safety and effectiveness.

Dr. Mohamed Ali, the first dentist in San Francisco to get a Yomi, and Neocis Northern California robot integration specialist Alyssa Viscio. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

According to Dr. Ali, the robot makes the procedure easier on patients, many of whom have never heard of Yomi or robot-assisted surgery in general. “They come because they have broken teeth and they want a solution,” he says. “But then when they know that the surgery is going to be very minimally invasive and the recovery is going to be fast . . . they feel much more comfortable and confident.”

How it works

Dr. Ali’s practice occupies the 19th floor of an old and ornate high-rise near Union Square in San Francisco. At first glance it looks like a normal dentist’s office. But soon you notice that there are a lot of computer screens around (mainly for showing dental imagery), and you get the sense that the practice is tech-forward. That impression is confirmed when you walk into the treatment rooms and see the robot. Yomi is basically a white medical cart with a large monitor extending from its top. Its only humanoid feature is its arm, which extends from a silver ball (the shoulder), bends at another silver ball (the elbow), and bends freely at another joint (the wrist) at the drill mechanism.

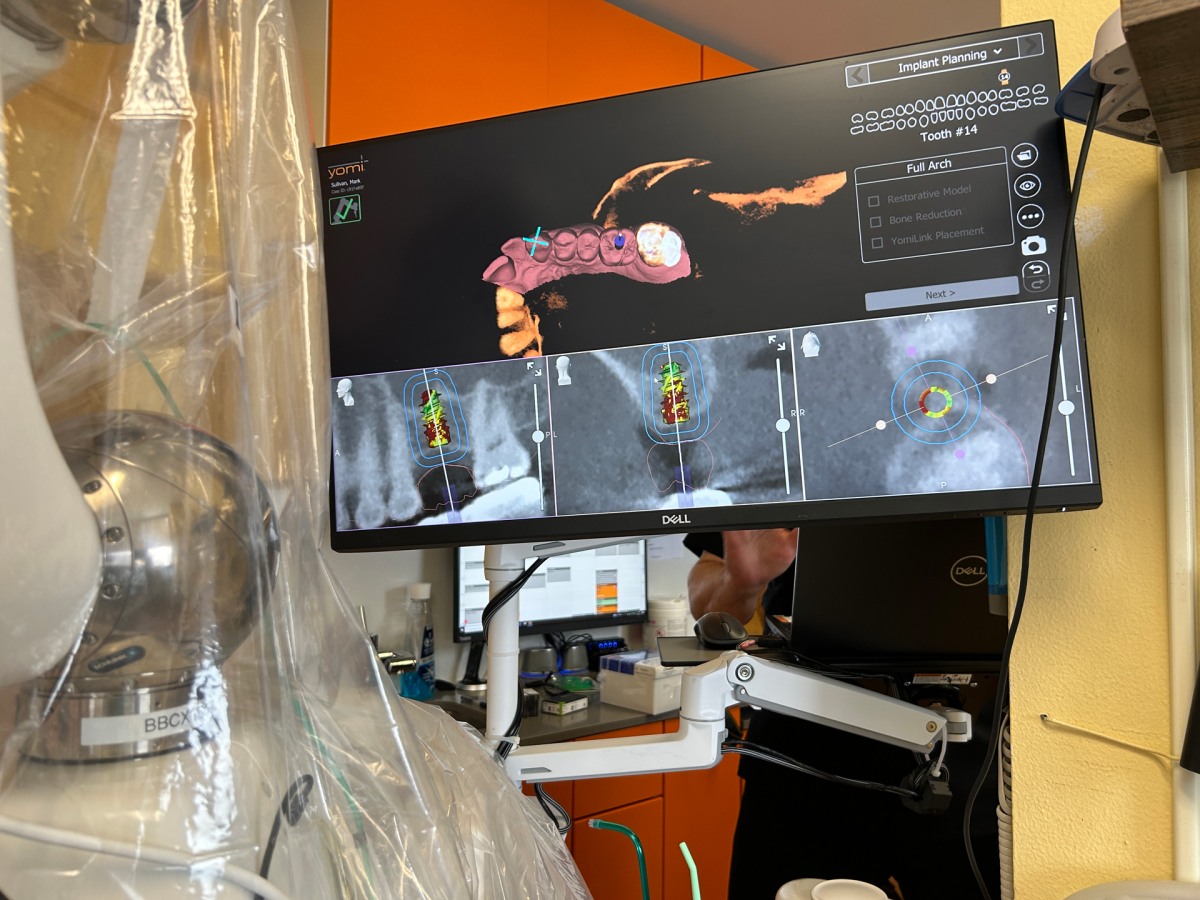

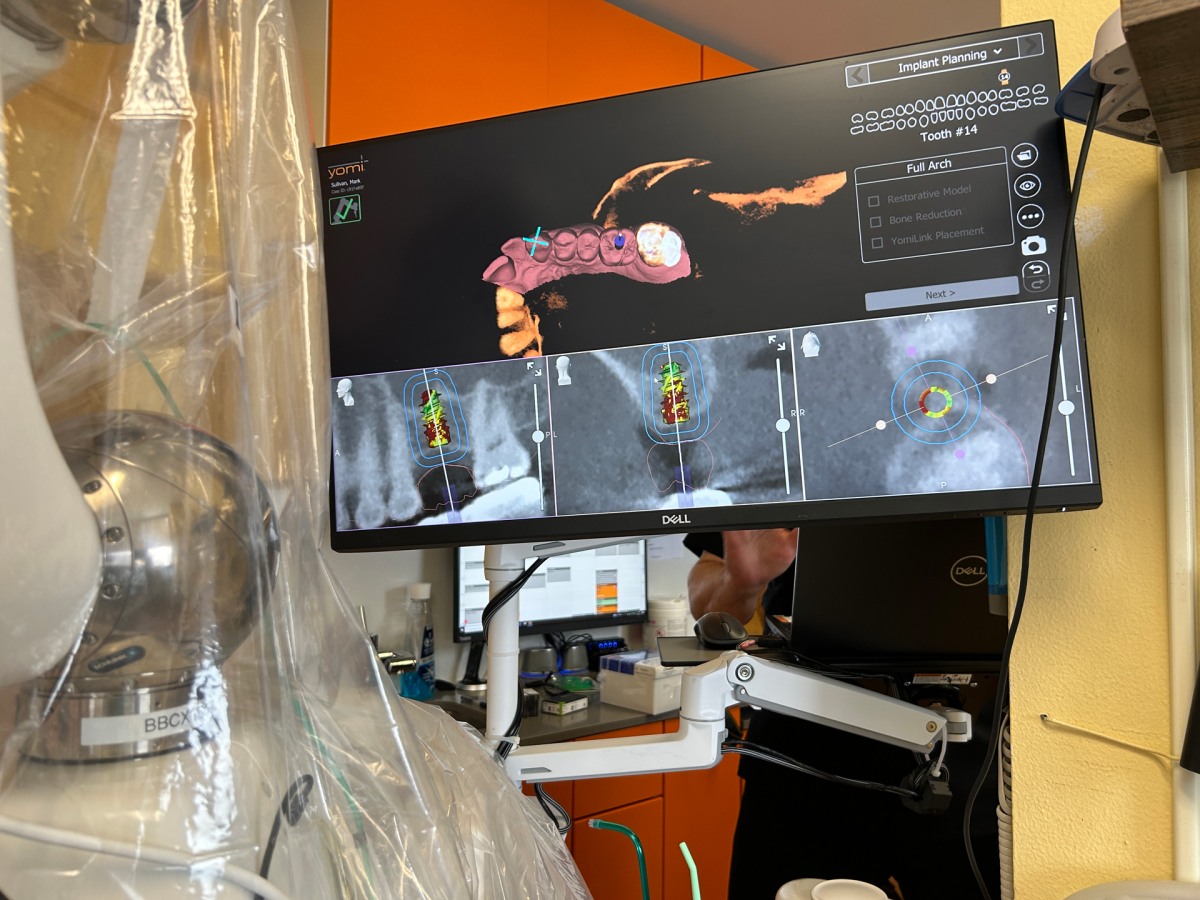

The Yomi system is a tight integration of 3D imaging software and the robotic arm. The implant procedure begins with a CT scan of the patient’s skull, including the mouth and jawbone. The CT scan is sent to Yomi, which then displays a very detailed 3D image. Using that image, the dentist and Yomi make a visual plan for the exact location, depth, and angle of the implant.

Yomi’s monitor displays the axis of the drilling angle for the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

Now Yomi had a spatial map of my mouth, but its software needed to sync up that image with the structure of my real-world mouth in order to navigate during the procedure. That is, it needed to understand exactly where the end of the arm was in relation to my jaw, even if my head moved slightly. To orient itself to that space, the robot’s software relies on another small piece of hardware called the “link,” which attaches to the lower teeth on the side opposite the implant site. Based on the position of the “link,” the Yomi software can sync up the 3D image to both the patient’s real-world mouth and to the location of the drill piece. With all parts of the system seeing the same thing, they can work together toward completing the plan—even if the patient’s head moves slightly.

The exactitude of this plan was particularly important for me, because the jaw bone that once held my missing tooth (No. 14) had atrophied somewhat. It was barely thick enough to accommodate the implant, and because No. 14 was located near my back molars, Dr. Ali would be drilling into the jawbone just below the floor of my sinus cavity. The implant needed to go up into my jawbone far enough to anchor, but not so far that it disturbed the sinus cavity.

Fortunately, Yomi excels at that kind of precision.

Dr. Ali uses the robot’s imaging software to form a plan to install the titanium implant at just the right angle and depth in the jaw bone. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

The Yomi arm moves freely around until it gets near the patient’s mouth. Then it goes into “guided” mode, giving the dentist feedback on movement of the drill in relation to the patient’s mouth. The drill moves easily when it’s advancing toward a correct drilling position specified by the plan, and offers resistance when moving away from the correct position. It moves the dentist toward the correct drilling angle. Sometimes the robot offers more than resistance. Had Dr. Ali moved the drill too close to my sinus cavity it would have refused to continue in that direction.

As the implant was going in I could feel the upward pressure on my jaw at tooth 14. It took some torque to get the implant in. I won’t call it a walk in the park, but it wasn’t painful. Many of Dr. Ali’s patients choose to be anesthetized during the procedure, but for the purposes of reporting I chose to stay awake. In about 30 minutes it was all over. A little woozy from the novacaine, I heard Dr. Ali say the implant had been placed perfectly and never touched my sinus wall. That night I had some ache in my jaw when the novocaine wore off, but nothing a couple of Tylenols couldn’t handle.

Neocis

The Miami-based company called Neocis, which has been busy over the past few years working with surgeons like Dr. Ali around the country to introduce the dental industry to Yomi. Neocis was founded in 2008 by Alon Mozes and Juan Salcedo when they worked as engineers at MAKO Surgical, which produced a groundbreaking robotic system for orthopedic surgery. The two men realized that robotics could be a boon for dentistry, specifically invasive, high-touch procedures like implants. They founded Neocis the following year and started building what would become the Yomi system.

In 2012 the company raised $1.07 million in a Series A round led by medical robotics entrepreneur Fred Moll. By 2016 the robot had been through clinical trials and became the first robotic system to be cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for dental surgery. Neocis sold its first Yomi robot in 2017 (today the robots cost roughly $200,000 with additional monthly fees for upkeep and maintenance), and has now installed nearly 200 of them in the U.S. Yomis have placed 40,000 implants to date, Mozes says. To date Neocis has raised a total of $179 million over 14 years from investors including Peter Thiel’s Mithril fund, Norwest Venture Partners, and NVIDIA’s NVentures.

Technicians use a specialized CAD system to design the crown that screws into the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

“When dentists start buying these systems, they really start using it on a routine basis and that’s critical,” he says, “because we’ve seen other robotic surgery companies where they sell robots and they don’t necessarily get the utilization, which is really ultimately what defines adoption.”

Mozes claims Yomi can provide a platform into which dental practices can plug in all the systems and workflows needed to do an implant from the 3D imagery to the final placement of the crown. “[Yomi] is the only robotic system available in the industry where we can address the surgical phase,” he says. “It really gives us an opportunity to expand that into an entire platform across the entire implant workflow.”

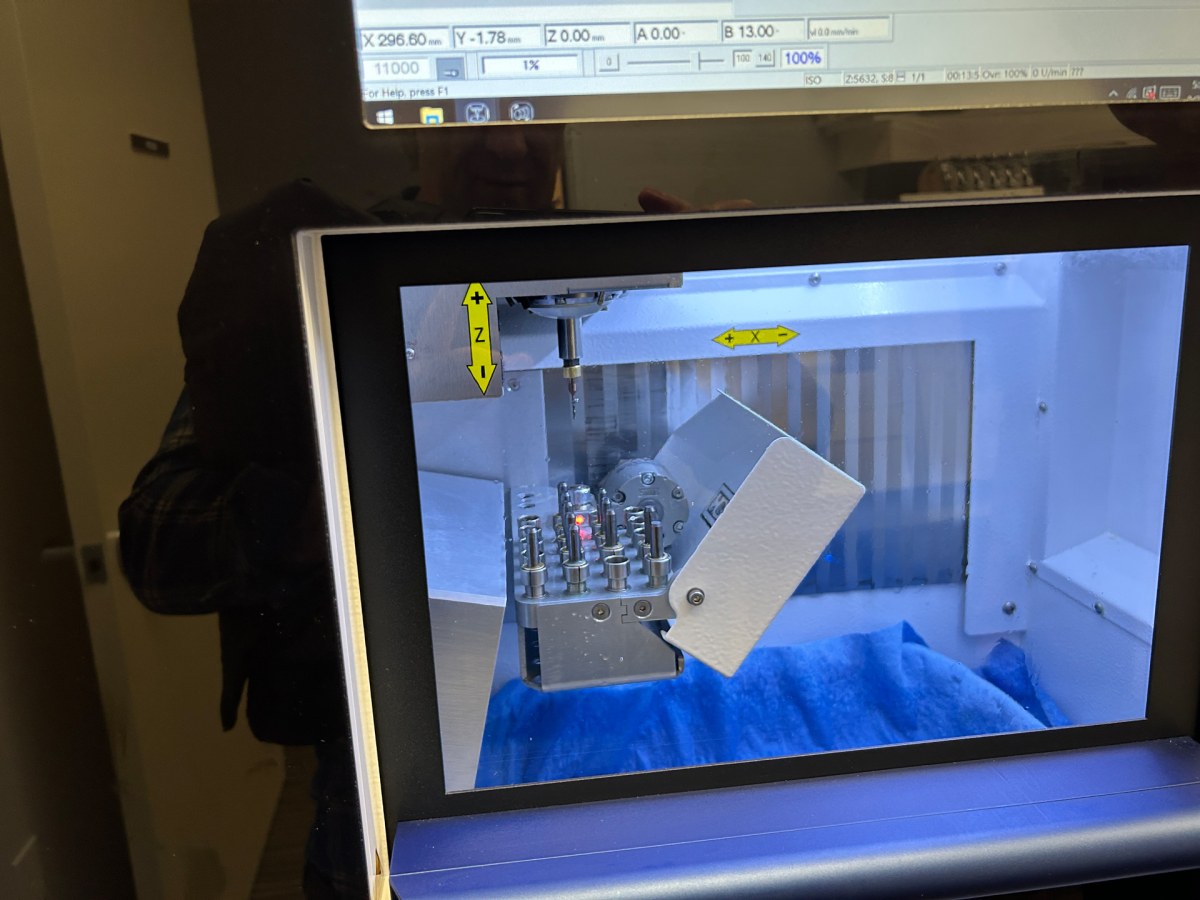

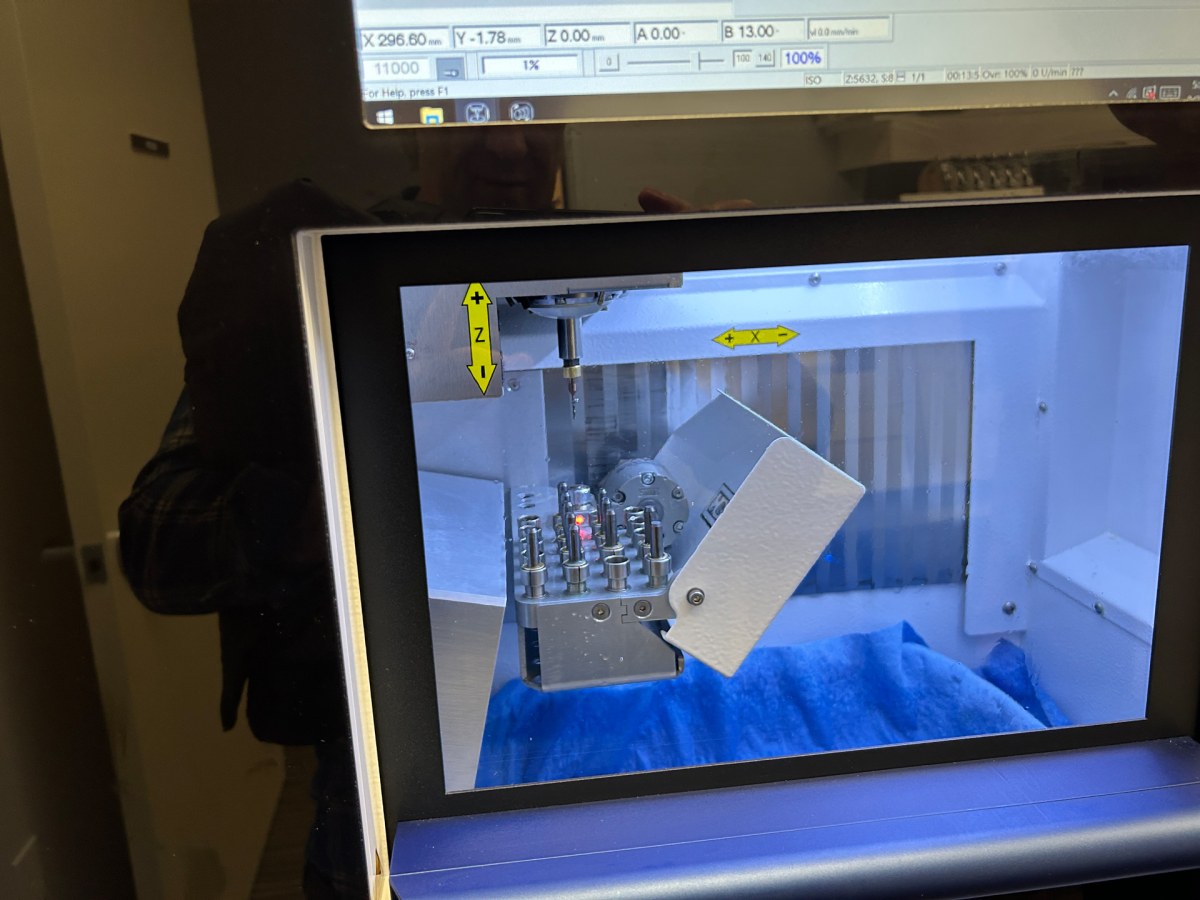

The Implants Pro Center uses a special milling machine to shape the crown to match the patient’s adjacent teeth. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

Case in point is Dr. Ali’s practice, which already offers the CT scans, the diagnostics and planning, and the robot to assist in the surgery. One floor down from the offices is another office space where technicians use a specialized CAD system that designs custom crowns for every implant patient. The CAD system plugs into a heavy-duty 3D printer that mills the new crowns. The only piece that Dr. Ali doesn’t currently produce in-house is the titanium implant itself, which is manufactured by a Swiss company called Straumann. “I’m planning to buy a 3D printer to print my own implants in the future, but that’s a very big project and requires FDA clearance,” Ali says.

Mozes says that as all those systems are united on one platform, AI might be used to automate more aspects of the process, with the goal of shortening the time interval between first meeting and placement of the crown.

A new trend in dentistry

Mozes and Salcedo are riding a wave that continues to grow. A wide array of medical procedures are now performed with the help of AI and robotics. Robots don’t practice medicine but they can make a big difference working alongside physicians. A robot can perform a procedure the exact same way every time, regardless of the experience or talent level of the surgeon. Studies have shown that treatment outcomes depend to a surprising degree on the training and experience of the human caregiver. Robots may help narrow that variance and make outcomes more predictable.

“A dentist who is not very well experienced in implant dentistry could still do 75% to 80% of the dental implant cases and do them very nicely and successfully,” Ali says. “There are cases where it will require additional skills or surgical skills when you need to do bone grafting and gum grafting.”

AI and robotics can be applied to procedures from high-stakes and high risk (repairing veins around the heart, for example), to relatively low stakes and low-risk procedures like dental implants. Now, dental schools in the U.S. are beginning to integrate robot-assisted dentistry into their curriculums. Several high-profile dental schools have already purchased Yomi systems for teaching, including Boston University, NYU, and the universities of Tennessee and West Virginia.

My new No. 14

I didn’t see Dr. Ali again for 12 weeks. My jawbone needed some time to heal and grow around the implant. During my next visit he moved away the small flaps of my gum and examined the implant. He screwed a metal piece called an abutment into the top of the implant. The abutment is like a metal post sticking up from the gumline; its job is to hold the crown, my new tooth. A technician came in and took pictures of my teeth so that the new crown would match.

Dr. Mohamed Ali, CEO of Implants Pro Center in San Francisco, and his assistant discuss the plan for installing the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

A few weeks later, Dr. Ali installed the new crown and fussed over its position in relation to the other teeth, and its effect on my bite. Long story short, it looked perfect and felt perfect. I realized that I’d become so engrossed in the robot and the procedure that I’d forgotten that I was getting back something important to me that I’d lost. My own parents, who are older, came of age during an era of dentistry where it was common to just extract all the teeth and put in dentures. That seems primitive and ghastly to me now. “I’m here for you,” Dr. Ali said as I was leaving the office. “Enjoy your tooth.”

On the train ride home I ran my tongue over my new No. 14 and smiled.

The novocaine made the lower part of my face feel like a sack of wet cement. A faint tinny sound of muzak leaked into the room from somewhere above. A blue surgical drape rested over my face; the small white spot from the dentist’s headlamp danced over it then finally zeroed in on my mouth. I heard Dr. Mohamed Ali exchange some numbers—they sounded like fine coordinates—with an assistant bent over a laptop nearby. Then I heard the robot draw near and knew it was almost ready to begin its careful journey through my gum and down into my jawbone. Dr. Ali uttered a single word—“Guided”—and the drilling began.

Dr. Mohamed Ali was the first dentist in San Francisco to begin replacing missing teeth with the help of a robot called Yomi. The titanium implant he and Yomi installed in my jaw would eventually anchor a new (man-made) tooth to replace the one I’d lost after a failed root canal two years ago. Yomi’s purpose is to make implantation surgery a more exacting, and predictable, process for dentists. The system’s software develops a detailed spatial understanding of the patient’s mouth, then the robotic arm “guides” the dentist to the exact place, and angle, to drill. The 15-year-old healthtech company Neocis spent years building and refining Yomi, and then years more putting it through clinical trials to prove its safety and effectiveness.

Dr. Mohamed Ali, the first dentist in San Francisco to get a Yomi, and Neocis Northern California robot integration specialist Alyssa Viscio. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

According to Dr. Ali, the robot makes the procedure easier on patients, many of whom have never heard of Yomi or robot-assisted surgery in general. “They come because they have broken teeth and they want a solution,” he says. “But then when they know that the surgery is going to be very minimally invasive and the recovery is going to be fast . . . they feel much more comfortable and confident.”

How it works

Dr. Ali’s practice occupies the 19th floor of an old and ornate high-rise near Union Square in San Francisco. At first glance it looks like a normal dentist’s office. But soon you notice that there are a lot of computer screens around (mainly for showing dental imagery), and you get the sense that the practice is tech-forward. That impression is confirmed when you walk into the treatment rooms and see the robot. Yomi is basically a white medical cart with a large monitor extending from its top. Its only humanoid feature is its arm, which extends from a silver ball (the shoulder), bends at another silver ball (the elbow), and bends freely at another joint (the wrist) at the drill mechanism.

The Yomi system is a tight integration of 3D imaging software and the robotic arm. The implant procedure begins with a CT scan of the patient’s skull, including the mouth and jawbone. The CT scan is sent to Yomi, which then displays a very detailed 3D image. Using that image, the dentist and Yomi make a visual plan for the exact location, depth, and angle of the implant.

Yomi’s monitor displays the axis of the drilling angle for the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

Now Yomi had a spatial map of my mouth, but its software needed to sync up that image with the structure of my real-world mouth in order to navigate during the procedure. That is, it needed to understand exactly where the end of the arm was in relation to my jaw, even if my head moved slightly. To orient itself to that space, the robot’s software relies on another small piece of hardware called the “link,” which attaches to the lower teeth on the side opposite the implant site. Based on the position of the “link,” the Yomi software can sync up the 3D image to both the patient’s real-world mouth and to the location of the drill piece. With all parts of the system seeing the same thing, they can work together toward completing the plan—even if the patient’s head moves slightly.

The exactitude of this plan was particularly important for me, because the jaw bone that once held my missing tooth (No. 14) had atrophied somewhat. It was barely thick enough to accommodate the implant, and because No. 14 was located near my back molars, Dr. Ali would be drilling into the jawbone just below the floor of my sinus cavity. The implant needed to go up into my jawbone far enough to anchor, but not so far that it disturbed the sinus cavity.

Fortunately, Yomi excels at that kind of precision.

Dr. Ali uses the robot’s imaging software to form a plan to install the titanium implant at just the right angle and depth in the jaw bone. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

The Yomi arm moves freely around until it gets near the patient’s mouth. Then it goes into “guided” mode, giving the dentist feedback on movement of the drill in relation to the patient’s mouth. The drill moves easily when it’s advancing toward a correct drilling position specified by the plan, and offers resistance when moving away from the correct position. It moves the dentist toward the correct drilling angle. Sometimes the robot offers more than resistance. Had Dr. Ali moved the drill too close to my sinus cavity it would have refused to continue in that direction.

As the implant was going in I could feel the upward pressure on my jaw at tooth 14. It took some torque to get the implant in. I won’t call it a walk in the park, but it wasn’t painful. Many of Dr. Ali’s patients choose to be anesthetized during the procedure, but for the purposes of reporting I chose to stay awake. In about 30 minutes it was all over. A little woozy from the novacaine, I heard Dr. Ali say the implant had been placed perfectly and never touched my sinus wall. That night I had some ache in my jaw when the novocaine wore off, but nothing a couple of Tylenols couldn’t handle.

Neocis

The Miami-based company called Neocis, which has been busy over the past few years working with surgeons like Dr. Ali around the country to introduce the dental industry to Yomi. Neocis was founded in 2008 by Alon Mozes and Juan Salcedo when they worked as engineers at MAKO Surgical, which produced a groundbreaking robotic system for orthopedic surgery. The two men realized that robotics could be a boon for dentistry, specifically invasive, high-touch procedures like implants. They founded Neocis the following year and started building what would become the Yomi system.

In 2012 the company raised $1.07 million in a Series A round led by medical robotics entrepreneur Fred Moll. By 2016 the robot had been through clinical trials and became the first robotic system to be cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for dental surgery. Neocis sold its first Yomi robot in 2017 (today the robots cost roughly $200,000 with additional monthly fees for upkeep and maintenance), and has now installed nearly 200 of them in the U.S. Yomis have placed 40,000 implants to date, Mozes says. To date Neocis has raised a total of $179 million over 14 years from investors including Peter Thiel’s Mithril fund, Norwest Venture Partners, and NVIDIA’s NVentures.

Technicians use a specialized CAD system to design the crown that screws into the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

“When dentists start buying these systems, they really start using it on a routine basis and that’s critical,” he says, “because we’ve seen other robotic surgery companies where they sell robots and they don’t necessarily get the utilization, which is really ultimately what defines adoption.”

Mozes claims Yomi can provide a platform into which dental practices can plug in all the systems and workflows needed to do an implant from the 3D imagery to the final placement of the crown. “[Yomi] is the only robotic system available in the industry where we can address the surgical phase,” he says. “It really gives us an opportunity to expand that into an entire platform across the entire implant workflow.”

The Implants Pro Center uses a special milling machine to shape the crown to match the patient’s adjacent teeth. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

Case in point is Dr. Ali’s practice, which already offers the CT scans, the diagnostics and planning, and the robot to assist in the surgery. One floor down from the offices is another office space where technicians use a specialized CAD system that designs custom crowns for every implant patient. The CAD system plugs into a heavy-duty 3D printer that mills the new crowns. The only piece that Dr. Ali doesn’t currently produce in-house is the titanium implant itself, which is manufactured by a Swiss company called Straumann. “I’m planning to buy a 3D printer to print my own implants in the future, but that’s a very big project and requires FDA clearance,” Ali says.

Mozes says that as all those systems are united on one platform, AI might be used to automate more aspects of the process, with the goal of shortening the time interval between first meeting and placement of the crown.

A new trend in dentistry

Mozes and Salcedo are riding a wave that continues to grow. A wide array of medical procedures are now performed with the help of AI and robotics. Robots don’t practice medicine but they can make a big difference working alongside physicians. A robot can perform a procedure the exact same way every time, regardless of the experience or talent level of the surgeon. Studies have shown that treatment outcomes depend to a surprising degree on the training and experience of the human caregiver. Robots may help narrow that variance and make outcomes more predictable.

“A dentist who is not very well experienced in implant dentistry could still do 75% to 80% of the dental implant cases and do them very nicely and successfully,” Ali says. “There are cases where it will require additional skills or surgical skills when you need to do bone grafting and gum grafting.”

AI and robotics can be applied to procedures from high-stakes and high risk (repairing veins around the heart, for example), to relatively low stakes and low-risk procedures like dental implants. Now, dental schools in the U.S. are beginning to integrate robot-assisted dentistry into their curriculums. Several high-profile dental schools have already purchased Yomi systems for teaching, including Boston University, NYU, and the universities of Tennessee and West Virginia.

My new No. 14

I didn’t see Dr. Ali again for 12 weeks. My jawbone needed some time to heal and grow around the implant. During my next visit he moved away the small flaps of my gum and examined the implant. He screwed a metal piece called an abutment into the top of the implant. The abutment is like a metal post sticking up from the gumline; its job is to hold the crown, my new tooth. A technician came in and took pictures of my teeth so that the new crown would match.

Dr. Mohamed Ali, CEO of Implants Pro Center in San Francisco, and his assistant discuss the plan for installing the implant. [Photo: Mark Sullivan]

A few weeks later, Dr. Ali installed the new crown and fussed over its position in relation to the other teeth, and its effect on my bite. Long story short, it looked perfect and felt perfect. I realized that I’d become so engrossed in the robot and the procedure that I’d forgotten that I was getting back something important to me that I’d lost. My own parents, who are older, came of age during an era of dentistry where it was common to just extract all the teeth and put in dentures. That seems primitive and ghastly to me now. “I’m here for you,” Dr. Ali said as I was leaving the office. “Enjoy your tooth.”

On the train ride home I ran my tongue over my new No. 14 and smiled.