Essay: Growing up Jewish in India

My favourite story is about a young TV anchor who could not pronounce my name nor believe that I was a Jew. She was surprised that I looked like an Indian and spoke fluent Gujarati. I suppose it’s because I do not stand out in an Indian crowd and it is difficult to immediately gauge that I am a Bene Israel Jew. The anchor had also collected some misleading information that I had been living in Israel and had only recently arrived in India. She expressed surprise that I had become Indian in such a short time! All this after I gave her an hour-long lecture about the history of Jews in India. She was not convinced. Sometimes this can be annoying and also amusing.

Ever since my childhood and during my teens and subsequently too, with a name like mine, I was often asked about my religion, community, city, village, region and country of origin. When I said, “I am a Bene Israel Jew”, most people behaved like they understood and began talking in superlatives about the agricultural expertise of Israel. From their expressions, I knew, of course, that they were confused. The next question invariably was whether I was from Israel.

Wearily, I’d respond with “I am an Indian”.

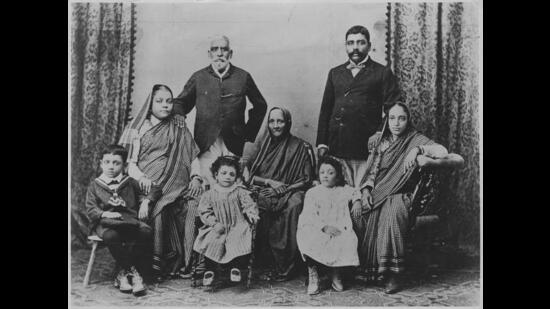

Today, there are about 4000 Jews in India, with about 140 in Gujarat, which makes us a mini-microscopic-minority community. About 2000 years ago, while fleeing the persecution of Greek warlords, a community of Jews arrived in India from Israel after their ship was wrecked off the coast of Alibaug in Maharashtra.

Jews have never faced persecution in India and live in peace with other communities. What I like best about being a minority in India is that it allows me to be who I am. We have been a part of India and will continue to be so.

Jews have been living in India for so long that to preserve their Jewish identity, the elders had created a list of rules. Through the years, I have learnt to deal with these restrictions and feel comfortable at the synagogue in Ahmedabad, for New Year celebrations, Yom Kippur prayers, Friday Shabbat prayers or when the Shofar is blown for certain festivals. On these occasions, prayers are chanted in Hebrew, but we speak in Marathi, Gujarati and English.

I feel attracted to Indian festivals, but I often feel like an outsider too.

My outsider syndrome continues to bother me even at the synagogue. As I am not fully conversant with Jewish rituals, there are moments when I feel like a minority within a minority community. Indeed, I am the classic example of the insider who suffers from the outsider syndrome.

When we lived with my grandmother, we kept the Shabbat, celebrated festivals and helped her to prepare the ‘malida’ platter or traditional food, as she made sure that the whole family went to the synagogue for community gatherings.

I was very close to her.

Later, my parents moved out of the old family home and into a small rented house. Suddenly, the warmth and religious traditions that my grandmother had embodied disappeared. These reappeared much later in my life, when I started writing about the Jewish ethos in India. It was during this period that I began researching being Indian and Jewish, which brought me closer to my community.

It was almost like living a secret inner Jewish life.

When I work on a novel, I feel a sense of excitement. I am fascinated by this transformation, which actually started when I wanted to understand the Jewish community, which connects me to the Jewish Diaspora. My interest in Jewish artifacts, rites, rituals, and beliefs intermingled with Indian traditions and entered my novels.

Earlier, during Navratri, Jews could not participate in the raas-garba nor could we wear shimmering chaniya-choli suits, so we would sit on the sidelines aching to be part of the festivities. But in the 1960s, while I was a student at Vadodara’s fine arts college, I cheated and danced in borrowed dresses and even won prizes… So then why not play Holi! Surprisingly, I did not feel guilty about these closely guarded secrets.

Much later in 2012, I felt a sense of victory, when a young Jewish woman convinced her parents to organise a sangeet as part of her wedding celebrations a day before her traditional Jewish mehendi ceremony. Happily, I dressed in a sari to participate in this historical moment when almost everybody came dressed in chaniya-choli suits and the men wore fancy kurtas and churidars.

Since then, the raas-garba, organized in the pavilion next to the synagogue, has become a regular feature.

Through the years, I have also learnt to create confusion about my name. On the telephone, very few people catch the pronunciation and I quickly change Esther to Asha or Astha and peace prevails at the other end of the line. Even the surname helps as I change David to Devi, suddenly becoming Asha Devi! Sometimes, I wish my name was a simple Mina Patel or Lata Shah. Well, whatever my name, as I often say, I am definitely a Good-Jew – Gujju!

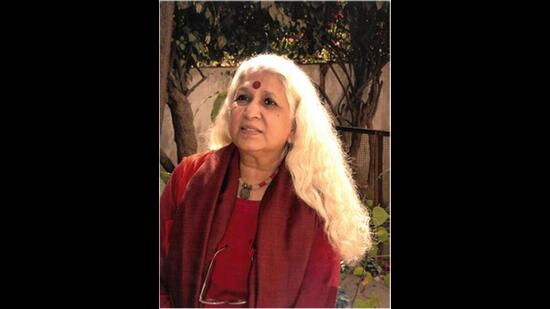

Esther David is an author. Her latest book is Bene Apetit; The Cuisine of Indian Jews.

My favourite story is about a young TV anchor who could not pronounce my name nor believe that I was a Jew. She was surprised that I looked like an Indian and spoke fluent Gujarati. I suppose it’s because I do not stand out in an Indian crowd and it is difficult to immediately gauge that I am a Bene Israel Jew. The anchor had also collected some misleading information that I had been living in Israel and had only recently arrived in India. She expressed surprise that I had become Indian in such a short time! All this after I gave her an hour-long lecture about the history of Jews in India. She was not convinced. Sometimes this can be annoying and also amusing.

Ever since my childhood and during my teens and subsequently too, with a name like mine, I was often asked about my religion, community, city, village, region and country of origin. When I said, “I am a Bene Israel Jew”, most people behaved like they understood and began talking in superlatives about the agricultural expertise of Israel. From their expressions, I knew, of course, that they were confused. The next question invariably was whether I was from Israel.

Wearily, I’d respond with “I am an Indian”.

Today, there are about 4000 Jews in India, with about 140 in Gujarat, which makes us a mini-microscopic-minority community. About 2000 years ago, while fleeing the persecution of Greek warlords, a community of Jews arrived in India from Israel after their ship was wrecked off the coast of Alibaug in Maharashtra.

Jews have never faced persecution in India and live in peace with other communities. What I like best about being a minority in India is that it allows me to be who I am. We have been a part of India and will continue to be so.

Jews have been living in India for so long that to preserve their Jewish identity, the elders had created a list of rules. Through the years, I have learnt to deal with these restrictions and feel comfortable at the synagogue in Ahmedabad, for New Year celebrations, Yom Kippur prayers, Friday Shabbat prayers or when the Shofar is blown for certain festivals. On these occasions, prayers are chanted in Hebrew, but we speak in Marathi, Gujarati and English.

I feel attracted to Indian festivals, but I often feel like an outsider too.

My outsider syndrome continues to bother me even at the synagogue. As I am not fully conversant with Jewish rituals, there are moments when I feel like a minority within a minority community. Indeed, I am the classic example of the insider who suffers from the outsider syndrome.

When we lived with my grandmother, we kept the Shabbat, celebrated festivals and helped her to prepare the ‘malida’ platter or traditional food, as she made sure that the whole family went to the synagogue for community gatherings.

I was very close to her.

Later, my parents moved out of the old family home and into a small rented house. Suddenly, the warmth and religious traditions that my grandmother had embodied disappeared. These reappeared much later in my life, when I started writing about the Jewish ethos in India. It was during this period that I began researching being Indian and Jewish, which brought me closer to my community.

It was almost like living a secret inner Jewish life.

When I work on a novel, I feel a sense of excitement. I am fascinated by this transformation, which actually started when I wanted to understand the Jewish community, which connects me to the Jewish Diaspora. My interest in Jewish artifacts, rites, rituals, and beliefs intermingled with Indian traditions and entered my novels.

Earlier, during Navratri, Jews could not participate in the raas-garba nor could we wear shimmering chaniya-choli suits, so we would sit on the sidelines aching to be part of the festivities. But in the 1960s, while I was a student at Vadodara’s fine arts college, I cheated and danced in borrowed dresses and even won prizes… So then why not play Holi! Surprisingly, I did not feel guilty about these closely guarded secrets.

Much later in 2012, I felt a sense of victory, when a young Jewish woman convinced her parents to organise a sangeet as part of her wedding celebrations a day before her traditional Jewish mehendi ceremony. Happily, I dressed in a sari to participate in this historical moment when almost everybody came dressed in chaniya-choli suits and the men wore fancy kurtas and churidars.

Since then, the raas-garba, organized in the pavilion next to the synagogue, has become a regular feature.

Through the years, I have also learnt to create confusion about my name. On the telephone, very few people catch the pronunciation and I quickly change Esther to Asha or Astha and peace prevails at the other end of the line. Even the surname helps as I change David to Devi, suddenly becoming Asha Devi! Sometimes, I wish my name was a simple Mina Patel or Lata Shah. Well, whatever my name, as I often say, I am definitely a Good-Jew – Gujju!

Esther David is an author. Her latest book is Bene Apetit; The Cuisine of Indian Jews.