Essay: On Andrea Camilleri’s Inspector Montalbano series

When Andrea Camilleri died in 2018, at the ripe age of 93, he left not a void but a full and rich granary, something that still feeds the millions of readers who mourned his passing. His Inspector Montalbano series, brought to us through Stephen Sartarelli’s brilliant translations, are among those books that can be read multiple times and still afford the same amount of pleasure. The bonus is watching the TV series.

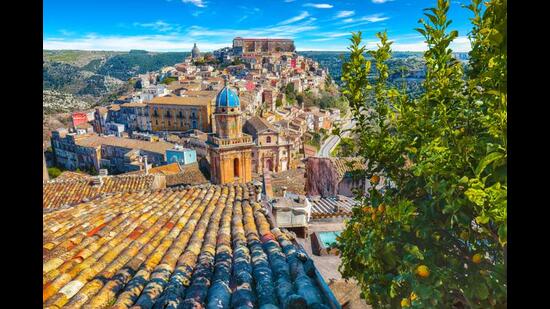

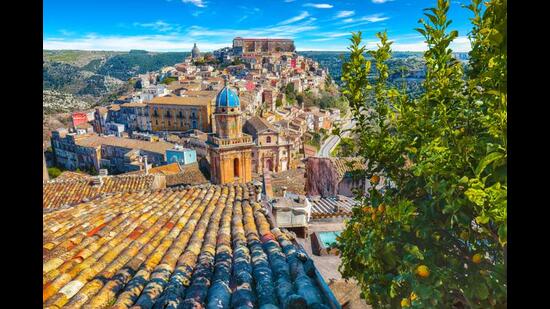

Camilleri started on the first Inspector Montalbano novel when he was 70, as an experiment that would presumably end with the first book. His inspiration came from an essay on the rules of writing a detective novel by Leonardo Sciascia and also from working alongside Diego Fabbri, who adapted Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels for television. At the same time, he took up the challenge of writing a detective story based in Sicily, which Italo Calvino had stated to be impossible. He also wanted a break from writing his ‘historical novel’, The Brewer of Preston. But his is a classic example of the author’s creation taking over his life, something he had so far disbelieved. Montalbano soon became his alter ego and spokesman in the two dozen or more books that he wound up writing. Want of space prevents me from writing all I want. Besides, where would I begin and where end?

There is, for instance, his intertextual and allusive narrative in which we might find Pirandello, Faulkner, James Joyce, Leonardo Sciascia and Manuel Vasquez-Montalban — in fact, the name of Camilleri’s detective, Salvo Montalbano, is a homage paid to Montalban.

Camilleri is said to have invented his own language: what he used was Italian for formal conversation and dialect for conversations among peers. Sartarelli’s use of cockney and mispronunciations where necessary is a stroke of genius. Ribald humour and wit season much of the narrative. Most of the comic relief, however, comes in the person of Catarella, “poisonally in poisson”, and his linguistic and cognitive disabilities. One of many instances is when Catarella, in The Terracotta Dog, asks his Chief for the name of a medical specialist.

“Specialist in what, Cat?”

“Gonorrhoea.”

Montalbano had looked at him open-mouthed.

“Gonorrhoea? You? When did you get that?”

“I got it first when I was still a li’l thing not yet six or seven years old.”

“What the hell are you saying, Cat? Are you sure you mean gonorrhoea?”

“Absolutely. Had it all my life, on and off. It’s here and gone, here and gone. Gonorrhoea.”

On the serious side, Camilleri’s radical political views and open criticism of the Berlusconi government, which he saw as the rightful spawn of the fascist regime of the past, provoked the ire of the Right wing but he responded to it with airy disclaimers, such the note which appears at the end of The Shape of Water:

“I believe it essential to state that this story was not taken from crime news and does not involve any real events. It is, in short, to be ascribed entirely to my imagination. But since in recent years reality has seemed bent on surpassing the imagination, if not entirely abolishing it, there may be a few unpleasant coincidences of name and situation. As we know, however, one cannot be held responsible for the whims of chance.

A repressive regime breeds moral and emotional corruption, which affects every sphere of personal and social life. And it follows that the investigation of any one crime exposes others that point to the greed and cruelty that only humans are capable of; and consequently, to the divorce of sex from love. As Camilleri himself put it, ‘I deliberately decided to smuggle into a detective novel a critical commentary of my times.”

To write about the mafiosi is almost unavoidable for a crime writer in Sicily. However, in Camilleri’s novels the mafiosi play a secondary role, “…not because I fear them but I believe writing about the mafiosi often makes heroes out of them…This is a gift I have no intention of offering to the mafia.”

Above all, there is the protagonist himself. Characters and situations unveil themselves through his experience and perceptions. Thus, we enter his world and share his affinities and aversions, his sensitivity, his lack of career ambitions and strong sense of justice; his unease with the process of ageing but with vitality for life – and so much more. I have decided to confine myself, therefore, to what appears to me as the important thing in Montalbano’s life – food and his enjoyment of it. This is apparent in all the novels so I will select a few samples from the first three novels, The Shape of Water, The Terracotta Dog and The Snack Thief.

Food is the counterpoint to the grimness of violent death, for there is constant celebration of life in food. An over-cooked pasta can create a black mood in Montalbano, but reminiscing about the flavours of a tabisca can immediately lift his spirits. One wonders if he loves good food even more than Livia when he tries to dissuade her from coming to Vigata on a day that he has been invited to dine with the Commissioner. Unable to dissuade her, he resigns himself dispiritedly to missing Signora Elisa’s cooking. His relief when both he and Livia receive the invitation is palpable.

Montalbano’s heroes in these novels are Calogero and Tanini, and with them is his housekeeper, Adelina, and Signora Elisa, who leaves Montalbano speechless, looking like “a stray dog awarded a caress”. In describing food Camilleri reaches heights of poetic fancy:

…eight pieces of hake arrived…crying out their joy – at having been cooked the way God had meant them to be’. Good food demands respect and reverence, and silence during a meal is how it is paid. Conversely, indifferent cooking awakens scorn in the same way that another’s unrefined taste also does:

Mimi proceeded to sprinkle a generous helping of Parmesan cheese over his plate. Christ! Even a hyena, which being a hyena, feeds on carrion, would have been sickened to see a dish of pasta with clam sauce covered with Parmesan!’

The detective who relishes food is an archetype: Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe, Georges Simenon’s Maigret, Montalban’s Carvalho being among the notable. But what sets Camilleri’s Montalbano apart is his appreciation of the essential flavours of native Sicilian cooking, delicate and seductive. Signora Elisa’s cooking is described thus: Supper was light, yet cooked, in every regard, with a touch the Lord grants very rarely to the Chosen.

In matters of taste, Montalbano is closer to Maigret than Carvalho, “who stuffed himself with dishes that would have set a shark’s belly on fire.” This is true. Carvalho’s dish of fried aubergines baked layered with ham, shrimps and cheese would probably have done just that to Montalbano himself. This is not to say that he has no taste for the exotic. Adelina receives a hug for her pasta con le sarde, which is spaghetti cooked with sardines, pine nuts and raisins, a native Sicilian dish with North African influences, and purpi alla carrettera, a Sicilian antipasto – “exquisite but deadly”.

Even on ordinary days when Adelina has left food in the fridge for Montalbano’s dinner the reader feels the same thrill of anticipation as he does: there might be cold pasta with olive oil, lemon and black olives, and a second dish of boiled shrimp dressed in olive oil and lemon. As he breathes in their flavours there is vicarious pleasure on the part of the reader. When his friend, Zito, suggests a garnish of parsley the reader nods assent. Then there is Montalbano’s comfort food: potatoes and onions in the same proportion “boiled for a long time” and seasoned with salt, pepper and olive oil. Maybe a garnish of parsley here, too?

Most of what he enjoys consists of fresh fish and seafood, simply boiled and dressed to retain their flavours. Tanini, a former crook who reinvents himself as a chef in Mazara, is talented enough to make Montalbano make a risky U-turn and drive back from half way to Vigata simply to ask him how he had cooked the striped mullet served for lunch. The pasta with crab he served for another lunch “was as graceful as a first-rate ballerina, but the stuffed bass in saffron sauce left him breathless, almost frightened”. However, Tanini’s masterpiece is something that finds an echo in our hearts:

Indignant at first when the second course arrives, which seemed to be meatballs (“Meatballs are for dogs!”) Montalbano follows his companion, who has by then uttered a soft moan of ecstasy, and sceptically ventures a first bite “…and with his tongue and palate began the scientific analysis…. So: fish and, no question, onion, hot pepper, whisked eggs, salt, pepper, breadcrumbs. But two other flavours, hiding under the taste of butter used in the frying, hadn’t yet answered the call. At the second mouthful he recognised what had escaped him in the first: cumin and coriander.

‘Koftas!’ he shouted in amazement.”

In the long months of lockdown during the pandemic it was Inspector Montalbano who kept me sane and relatively unscathed. He still does.

Indranee Ghosh is the author of Spiced, Smoked, Pickled, Preserved; Recipes and Reminiscences from India’s Eastern Hills.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

When Andrea Camilleri died in 2018, at the ripe age of 93, he left not a void but a full and rich granary, something that still feeds the millions of readers who mourned his passing. His Inspector Montalbano series, brought to us through Stephen Sartarelli’s brilliant translations, are among those books that can be read multiple times and still afford the same amount of pleasure. The bonus is watching the TV series.

Camilleri started on the first Inspector Montalbano novel when he was 70, as an experiment that would presumably end with the first book. His inspiration came from an essay on the rules of writing a detective novel by Leonardo Sciascia and also from working alongside Diego Fabbri, who adapted Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels for television. At the same time, he took up the challenge of writing a detective story based in Sicily, which Italo Calvino had stated to be impossible. He also wanted a break from writing his ‘historical novel’, The Brewer of Preston. But his is a classic example of the author’s creation taking over his life, something he had so far disbelieved. Montalbano soon became his alter ego and spokesman in the two dozen or more books that he wound up writing. Want of space prevents me from writing all I want. Besides, where would I begin and where end?

There is, for instance, his intertextual and allusive narrative in which we might find Pirandello, Faulkner, James Joyce, Leonardo Sciascia and Manuel Vasquez-Montalban — in fact, the name of Camilleri’s detective, Salvo Montalbano, is a homage paid to Montalban.

Camilleri is said to have invented his own language: what he used was Italian for formal conversation and dialect for conversations among peers. Sartarelli’s use of cockney and mispronunciations where necessary is a stroke of genius. Ribald humour and wit season much of the narrative. Most of the comic relief, however, comes in the person of Catarella, “poisonally in poisson”, and his linguistic and cognitive disabilities. One of many instances is when Catarella, in The Terracotta Dog, asks his Chief for the name of a medical specialist.

“Specialist in what, Cat?”

“Gonorrhoea.”

Montalbano had looked at him open-mouthed.

“Gonorrhoea? You? When did you get that?”

“I got it first when I was still a li’l thing not yet six or seven years old.”

“What the hell are you saying, Cat? Are you sure you mean gonorrhoea?”

“Absolutely. Had it all my life, on and off. It’s here and gone, here and gone. Gonorrhoea.”

On the serious side, Camilleri’s radical political views and open criticism of the Berlusconi government, which he saw as the rightful spawn of the fascist regime of the past, provoked the ire of the Right wing but he responded to it with airy disclaimers, such the note which appears at the end of The Shape of Water:

“I believe it essential to state that this story was not taken from crime news and does not involve any real events. It is, in short, to be ascribed entirely to my imagination. But since in recent years reality has seemed bent on surpassing the imagination, if not entirely abolishing it, there may be a few unpleasant coincidences of name and situation. As we know, however, one cannot be held responsible for the whims of chance.

A repressive regime breeds moral and emotional corruption, which affects every sphere of personal and social life. And it follows that the investigation of any one crime exposes others that point to the greed and cruelty that only humans are capable of; and consequently, to the divorce of sex from love. As Camilleri himself put it, ‘I deliberately decided to smuggle into a detective novel a critical commentary of my times.”

To write about the mafiosi is almost unavoidable for a crime writer in Sicily. However, in Camilleri’s novels the mafiosi play a secondary role, “…not because I fear them but I believe writing about the mafiosi often makes heroes out of them…This is a gift I have no intention of offering to the mafia.”

Above all, there is the protagonist himself. Characters and situations unveil themselves through his experience and perceptions. Thus, we enter his world and share his affinities and aversions, his sensitivity, his lack of career ambitions and strong sense of justice; his unease with the process of ageing but with vitality for life – and so much more. I have decided to confine myself, therefore, to what appears to me as the important thing in Montalbano’s life – food and his enjoyment of it. This is apparent in all the novels so I will select a few samples from the first three novels, The Shape of Water, The Terracotta Dog and The Snack Thief.

Food is the counterpoint to the grimness of violent death, for there is constant celebration of life in food. An over-cooked pasta can create a black mood in Montalbano, but reminiscing about the flavours of a tabisca can immediately lift his spirits. One wonders if he loves good food even more than Livia when he tries to dissuade her from coming to Vigata on a day that he has been invited to dine with the Commissioner. Unable to dissuade her, he resigns himself dispiritedly to missing Signora Elisa’s cooking. His relief when both he and Livia receive the invitation is palpable.

Montalbano’s heroes in these novels are Calogero and Tanini, and with them is his housekeeper, Adelina, and Signora Elisa, who leaves Montalbano speechless, looking like “a stray dog awarded a caress”. In describing food Camilleri reaches heights of poetic fancy:

…eight pieces of hake arrived…crying out their joy – at having been cooked the way God had meant them to be’. Good food demands respect and reverence, and silence during a meal is how it is paid. Conversely, indifferent cooking awakens scorn in the same way that another’s unrefined taste also does:

Mimi proceeded to sprinkle a generous helping of Parmesan cheese over his plate. Christ! Even a hyena, which being a hyena, feeds on carrion, would have been sickened to see a dish of pasta with clam sauce covered with Parmesan!’

The detective who relishes food is an archetype: Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe, Georges Simenon’s Maigret, Montalban’s Carvalho being among the notable. But what sets Camilleri’s Montalbano apart is his appreciation of the essential flavours of native Sicilian cooking, delicate and seductive. Signora Elisa’s cooking is described thus: Supper was light, yet cooked, in every regard, with a touch the Lord grants very rarely to the Chosen.

In matters of taste, Montalbano is closer to Maigret than Carvalho, “who stuffed himself with dishes that would have set a shark’s belly on fire.” This is true. Carvalho’s dish of fried aubergines baked layered with ham, shrimps and cheese would probably have done just that to Montalbano himself. This is not to say that he has no taste for the exotic. Adelina receives a hug for her pasta con le sarde, which is spaghetti cooked with sardines, pine nuts and raisins, a native Sicilian dish with North African influences, and purpi alla carrettera, a Sicilian antipasto – “exquisite but deadly”.

Even on ordinary days when Adelina has left food in the fridge for Montalbano’s dinner the reader feels the same thrill of anticipation as he does: there might be cold pasta with olive oil, lemon and black olives, and a second dish of boiled shrimp dressed in olive oil and lemon. As he breathes in their flavours there is vicarious pleasure on the part of the reader. When his friend, Zito, suggests a garnish of parsley the reader nods assent. Then there is Montalbano’s comfort food: potatoes and onions in the same proportion “boiled for a long time” and seasoned with salt, pepper and olive oil. Maybe a garnish of parsley here, too?

Most of what he enjoys consists of fresh fish and seafood, simply boiled and dressed to retain their flavours. Tanini, a former crook who reinvents himself as a chef in Mazara, is talented enough to make Montalbano make a risky U-turn and drive back from half way to Vigata simply to ask him how he had cooked the striped mullet served for lunch. The pasta with crab he served for another lunch “was as graceful as a first-rate ballerina, but the stuffed bass in saffron sauce left him breathless, almost frightened”. However, Tanini’s masterpiece is something that finds an echo in our hearts:

Indignant at first when the second course arrives, which seemed to be meatballs (“Meatballs are for dogs!”) Montalbano follows his companion, who has by then uttered a soft moan of ecstasy, and sceptically ventures a first bite “…and with his tongue and palate began the scientific analysis…. So: fish and, no question, onion, hot pepper, whisked eggs, salt, pepper, breadcrumbs. But two other flavours, hiding under the taste of butter used in the frying, hadn’t yet answered the call. At the second mouthful he recognised what had escaped him in the first: cumin and coriander.

‘Koftas!’ he shouted in amazement.”

In the long months of lockdown during the pandemic it was Inspector Montalbano who kept me sane and relatively unscathed. He still does.

Indranee Ghosh is the author of Spiced, Smoked, Pickled, Preserved; Recipes and Reminiscences from India’s Eastern Hills.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading