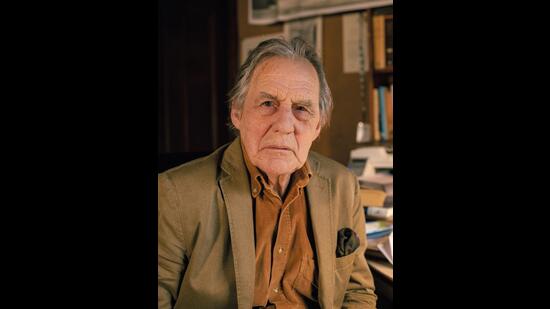

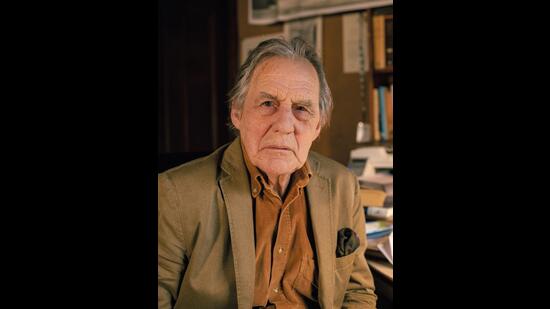

Excerpt: Himalaya by John Keay

…Visitors to Darjeeling are urged to rise early. From this ramshackle city slung across once lush hillsides at the northern apex of the Indian state of West Bengal the best chance of a close encounter with the world’s most spectacular urban backdrop comes at first light. Even then you may be disappointed. Kangchenjunga (Kangchendzonga), our planet’s third highest mountain, is like the tiger in the forest – ever out there but not readily spotted. Or more accurately, it’s ever up there. Instead of straining towards some pearly peak on a distant horizon, you need to crane backwards. The mountain is overhead; and though the snows of its summit are billowed in cloud, should it deign to disrobe, be prepared for a vision. You’re standing beneath an apotheosis, a shy, radiant deity. Even empire-builders never forgot their first sighting of Kangchenjunga.

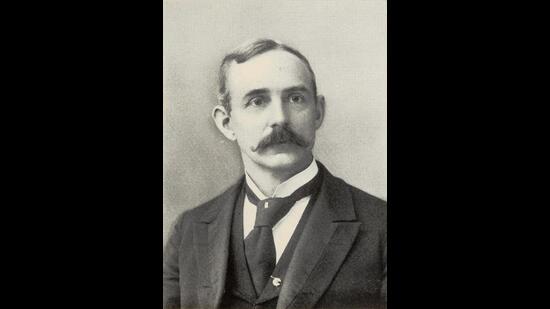

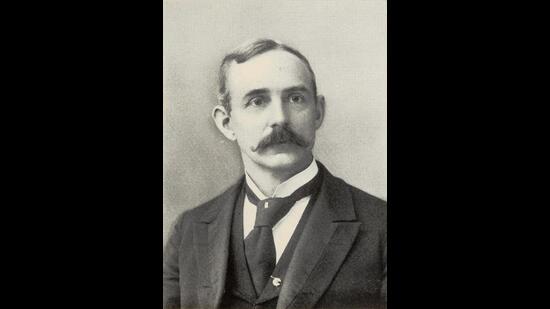

It is Friday 19 June 1903. Dawn comes up grey and unpromising. The monsoon has just broken and the rain is said to have been ‘coming down in cataracts’. This inconvenience fails to deter a small group of sightseers gathered outside the town’s Rockville Hotel. The mountain is anyway invisible from the narrow lanes round the Rockville, and here at this unearthly hour there is another attraction. Horses are being saddled, servants berated, last-minute orders issued. By the time the newly appointed commissioner for Tibetan frontier affairs emerges from the hotel, all is ready. A short figure with a droopy moustache, receding hairline and not much in the way of small talk, the fortyyear-old Captain Francis Edward Younghusband is dressed, beneath his dripping oilskins, in ‘Marching order’ – ‘breeches, gaiters, brown boots, flannel shirt, khaki coat and forage cap’. The captain mounts, his escort forms up and the cavalcade clatters off. They head north for Sikkim and Tibet. As the rain hammers down, someone is heard to call out ‘Good luck.’ With half a dozen Himalayan passes to cross, a near-polar winter in prospect and 650 kilometres of the world’s most hostile terrain, they need more than luck.

Four months later the captain, now promoted to colonel, is back in Darjeeling. Luck has failed him; Tibet is no-go. Not for the first time – but the last if Younghusband has anything to do with it – an expedition angling for permission to visit the Tibetan capital of Lhasa has been rebuffed. The mission was supposed to have put relations between British-ruled India and Chinese-claimed Tibet on an amicable basis. A previous convention had promised reciprocal trade, border demarcation and respect for one another’s sovereign territory. But though the Chinese had signed this document, the Tibetans had not (and, according to the British, had the Tibetans signed it, the Chinese would not; collusion supposedly underlay the rejection). Lhasa had therefore felt entitled to remove the new boundary markers, claim grazing rights in their vicinity, nullify cross-border trade and return unopened any letters thought to be protesting against these actions.

Younghusband had counted on gaining Tibetan compliance by himself infringing the convention. With an escort of 500 mainly Indian troops plus countless servants, porters and pony-men, his mission had crossed the British-protected state of Sikkim and clambered up a pass 5,200 metres above sea level (asl) to set up camp at Khampa Dzong on Tibetan soil. There they had indeed been met by a Tibetan delegation. But the delegates were thought to be of inferior rank and neither empowered nor disposed to negotiate. Younghusband insisted that in the face of such intransigence his orders were to advance. The Tibetans insisted he must withdraw; only when his mission had vacated Tibetan territory might even talks about talks be sanctioned.

The stand-off had lasted from June till October. Younghusband hadn’t budged. The rains eased off and the thermometer began to plummet. Tibetan troops were reportedly mobilising to contest any further advance. A couple of Sikkimese subjects, who were entitled to British protection and were in fact British spies, were arrested and maltreated by the Tibetans. But that was only half the story.

These insults would never have given rise to the despatch of an expedition if the Tibetans had not added injury to them by their dalliance with Russia [wrote a well-informed correspondent of the London Times]. As it was, there was nothing else to do but intervene, and that speedily.

Speedily enough, orders had been drafted for a more forceful‘intervention’ well before Younghusband, leaving his escort at Khampa Dzong, rode back into Darjeeling. He was immediately summoned to Simla, the summer capital of the raj, to consult with Lord Curzon, the British viceroy. With more troops and greater firepower, the Younghusband ‘diplomatic mission’ of 1903 was about to be reconfigured as the Younghusband ‘military expedition’ of 1904. At the time the Tibetans and the Chinese rightly called it an ‘invasion’; subsequently even supporters would concede it was an ‘armed incursion’. The weaponry being readied included mountain artillery and the latest in death-dealing machine guns. ‘Whatever happens, we have got / The Maxim gun and they have not,’ quipped a Hilaire Belloc character in the only known maxim about the Maxim.

********

For an elevated wilderness as apparently impregnable, unproductive and physically demanding as Himālaya’s heartland, Tibet has attracted a surprising number of invaders. Many came from the north and east – Mongols, Jurchen, Manchus, Maoists and currently Han immigrants. Equally enticing were Himālaya’s outlying regions. Both Kashmir and Nepal had been repeatedly overrun from the south – by Rajputs, Afghans, Mughals, Dogras – while, from the same satellite kingdoms, invasions of Ladakh and Tibet itself had been mounted.

As early as 326 bce, Alexander the Great, when marching a detachment of his Macedonian veterans from northern Afghanistan to India, seems to have notched up conquests in Kafiristan (Nuristan), Chitral and Swat, valleys where Himālaya’s western fringes serve as India’s north-west frontier. Along the same frontier but more recently, British expeditions in the 1890s had fought their way into the mountain kingdoms of Hunza and Chitral (both now in Pakistan). Younghusband himself had been involved in these latter-day ventures, refuting Chinese claims to Hunza in the Karakorams as a political agent and reporting on the British occupation of Chitral in the Hindu Kush on a journalistic assignment. As an explorer and collector of military intelligence, he was already famous for exploits beyond India’s frontiers in the Pamirs and Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang). But perhaps Younghusband’s most useful discovery had been made in Chitral where, in 1894, while travelling the length of that valley in the company of a globe-trotting MP, he had found his future patron.

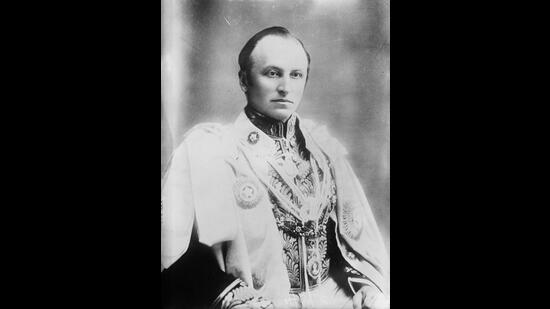

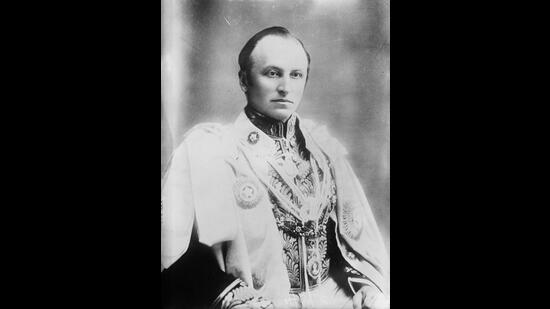

Francis Edward Younghusband, the soldier-explorer responsible for the 1904 invasion of Tibet Captain Francis Younghusband and the Hon. George Nathaniel Curzon MP appeared to have little in common. Younghusband, born into a military family in India, had belied his slight stature by winning cross-country races at school and going straight into the army. … Curzon, on the other hand, the heir to a barony, had garnered prizes at Eton and Balliol and been elected president of the Oxford Union… Few would doubt, least of all Curzon himself, that as a scholar and highly articulate parliamentarian he was destined for the highest office. His appointment in 1899 as the youngest ever viceroy seemed preordained and his six years of forceful rule would generally be reckoned to mark the apogee of the British raj.

But while Curzon winced at Younghusband’s naivety and Younghusband crumpled under Curzon’s interrogation, neither ever doubted their mutual commitment. In the face of criticism over an assignment like Tibet, Curzon could count on Younghusband’s expansionist instincts while Younghusband could bank on Curzon’s unwavering support. Fired by a sense of imperial mission, both believed that ‘Providence or the laws of destiny had called Britain to India for [in Curzon’s words] “the lasting benefit of the human race”.’

The benefit was thought self-evident and amply justified a degree of compulsion.

But British rule in India was constantly under threat, both from within and from without, and nowhere more so than on its long continental frontier in Himālaya. Here, beyond the mountains, another empire, that of tsarist Russia, was invoking Providence and the laws of destiny to justify extending its own lasting benefits to the human race.

It was an old story. Anglo-Russian rivalry in Inner Asia had been smouldering since Napoleonic times… Earlier an Irish cavalryman had called it ‘a great game’ – until, that is, his luck ran out when he was confined in a pit of snakes in Bukhara prior to being executed…

“the Great Game”… entered popular usage… when Kipling adopted the term in his much loved Kim, published in 1901. In that same year it was reported in St Petersburg that envoys from Tibet were being entertained in the Russian capital. They bore gifts and overtures from the young Dalai Lama and were accompanied by a man long resident in Lhasa whom the British identified as Aghvan Dorzhiev.

To those, like Curzon and Younghusband, of a decidedly bullish disposition, this news was as the reddest of red rags. Dorzhiev was portrayed as an unscrupulous adventurer and master of intrigue. It was not his first Russian visit and he was actually a Russian subject. But as a Buriat (Siberian) Mongol, he was a Buddhist by birth and had a genuine interest in Tibetan scholarship. He may have encouraged the Dalai Lama to challenge those of his ministers who favoured good relations with the British, and he may genuinely have believed that Tibetan Buddhism would be safer under the protection of Tsar Nicholas II, among whose subjects were several other Buddhist peoples, than under the newly crowned King Edward VII.

Curzon chose to believe that Dorzhiev had actually drawn up a Russo-Tibetan treaty; Younghusband was convinced that St Petersburg was supplying Lhasa with modern arms; and both men credited reports of a cossack detachment standing by to rush to Tibet’s aid whenever required…

…By November 1903 Younghusband was in Simla being briefed by Curzon. The new expedition was to have British troops as well as more Indian regiments, more and bigger guns, and a supply chain capable of supporting around 2,000 combat troops over vast distances and for several months. But according to a supposedly definitive statement issued by the Cabinet in London, the objectives had changed. The “sole purpose” of the expedition was now that of “obtaining satisfaction” for the recent border transgressions. To this end Younghusband might proceed as far as Gyantse, about halfway to Lhasa. He would withdraw as soon as “reparation is obtained”; no permanent mission was to be left in Tibet and no part of the country occupied… It was simply a punitive action…

The 1903 mission to Khampa Dzong had been shrouded in secrecy, but the 1904 expedition was to be a more public affair. Behind the advancing troops a telegraph line was being hastily erected, postal runners plied daily back to Darjeeling, and officers were allowed to bring along their cameras and sketching materials. Captain Walton was in charge of the natural history collection, a young geologist, Henry Hayden, was on loan from the Geological Survey, and Lieutenant Ryder from the map-making Survey of India. Austine Waddell, an elderly doctor, headed the medical team and, on the strength of previous acquaintance with the Buddhist traditions of Sikkim and Darjeeling, doubled as the expedition’s cultural attaché. Waddell helpfully lists at least five officers who were filing reports or writing articles for the press. In addition, accredited correspondents from The Times, Daily Mail and Reuter’s vied for front-line stories and marvelled at the strange land in which they found themselves. All, like Younghusband, wrote letters home and many, including Dr Waddell, subsequently produced detailed and handsomely illustrated accounts of the whole expedition.

From this mass of reportage, there emerges yet another incentive for the whole undertaking. Besides regulating frontier relations with the Tibetans, exacting satisfaction for their “insults” and countering Lhasa’s supposed overtures to tsarist Russia, the expedition would generate its own dynamic. What Waddell calls the “Land of Mystery”, “the mystic land of the lamas”, was exercising its allure, drawing the intruders onwards. In the thin air it seemed possible to do anything, go anywhere. Dispelling Tibet’s “forbidden” reputation and exploring its romance became ends in themselves.

…Visitors to Darjeeling are urged to rise early. From this ramshackle city slung across once lush hillsides at the northern apex of the Indian state of West Bengal the best chance of a close encounter with the world’s most spectacular urban backdrop comes at first light. Even then you may be disappointed. Kangchenjunga (Kangchendzonga), our planet’s third highest mountain, is like the tiger in the forest – ever out there but not readily spotted. Or more accurately, it’s ever up there. Instead of straining towards some pearly peak on a distant horizon, you need to crane backwards. The mountain is overhead; and though the snows of its summit are billowed in cloud, should it deign to disrobe, be prepared for a vision. You’re standing beneath an apotheosis, a shy, radiant deity. Even empire-builders never forgot their first sighting of Kangchenjunga.

It is Friday 19 June 1903. Dawn comes up grey and unpromising. The monsoon has just broken and the rain is said to have been ‘coming down in cataracts’. This inconvenience fails to deter a small group of sightseers gathered outside the town’s Rockville Hotel. The mountain is anyway invisible from the narrow lanes round the Rockville, and here at this unearthly hour there is another attraction. Horses are being saddled, servants berated, last-minute orders issued. By the time the newly appointed commissioner for Tibetan frontier affairs emerges from the hotel, all is ready. A short figure with a droopy moustache, receding hairline and not much in the way of small talk, the fortyyear-old Captain Francis Edward Younghusband is dressed, beneath his dripping oilskins, in ‘Marching order’ – ‘breeches, gaiters, brown boots, flannel shirt, khaki coat and forage cap’. The captain mounts, his escort forms up and the cavalcade clatters off. They head north for Sikkim and Tibet. As the rain hammers down, someone is heard to call out ‘Good luck.’ With half a dozen Himalayan passes to cross, a near-polar winter in prospect and 650 kilometres of the world’s most hostile terrain, they need more than luck.

Four months later the captain, now promoted to colonel, is back in Darjeeling. Luck has failed him; Tibet is no-go. Not for the first time – but the last if Younghusband has anything to do with it – an expedition angling for permission to visit the Tibetan capital of Lhasa has been rebuffed. The mission was supposed to have put relations between British-ruled India and Chinese-claimed Tibet on an amicable basis. A previous convention had promised reciprocal trade, border demarcation and respect for one another’s sovereign territory. But though the Chinese had signed this document, the Tibetans had not (and, according to the British, had the Tibetans signed it, the Chinese would not; collusion supposedly underlay the rejection). Lhasa had therefore felt entitled to remove the new boundary markers, claim grazing rights in their vicinity, nullify cross-border trade and return unopened any letters thought to be protesting against these actions.

Younghusband had counted on gaining Tibetan compliance by himself infringing the convention. With an escort of 500 mainly Indian troops plus countless servants, porters and pony-men, his mission had crossed the British-protected state of Sikkim and clambered up a pass 5,200 metres above sea level (asl) to set up camp at Khampa Dzong on Tibetan soil. There they had indeed been met by a Tibetan delegation. But the delegates were thought to be of inferior rank and neither empowered nor disposed to negotiate. Younghusband insisted that in the face of such intransigence his orders were to advance. The Tibetans insisted he must withdraw; only when his mission had vacated Tibetan territory might even talks about talks be sanctioned.

The stand-off had lasted from June till October. Younghusband hadn’t budged. The rains eased off and the thermometer began to plummet. Tibetan troops were reportedly mobilising to contest any further advance. A couple of Sikkimese subjects, who were entitled to British protection and were in fact British spies, were arrested and maltreated by the Tibetans. But that was only half the story.

These insults would never have given rise to the despatch of an expedition if the Tibetans had not added injury to them by their dalliance with Russia [wrote a well-informed correspondent of the London Times]. As it was, there was nothing else to do but intervene, and that speedily.

Speedily enough, orders had been drafted for a more forceful‘intervention’ well before Younghusband, leaving his escort at Khampa Dzong, rode back into Darjeeling. He was immediately summoned to Simla, the summer capital of the raj, to consult with Lord Curzon, the British viceroy. With more troops and greater firepower, the Younghusband ‘diplomatic mission’ of 1903 was about to be reconfigured as the Younghusband ‘military expedition’ of 1904. At the time the Tibetans and the Chinese rightly called it an ‘invasion’; subsequently even supporters would concede it was an ‘armed incursion’. The weaponry being readied included mountain artillery and the latest in death-dealing machine guns. ‘Whatever happens, we have got / The Maxim gun and they have not,’ quipped a Hilaire Belloc character in the only known maxim about the Maxim.

********

For an elevated wilderness as apparently impregnable, unproductive and physically demanding as Himālaya’s heartland, Tibet has attracted a surprising number of invaders. Many came from the north and east – Mongols, Jurchen, Manchus, Maoists and currently Han immigrants. Equally enticing were Himālaya’s outlying regions. Both Kashmir and Nepal had been repeatedly overrun from the south – by Rajputs, Afghans, Mughals, Dogras – while, from the same satellite kingdoms, invasions of Ladakh and Tibet itself had been mounted.

As early as 326 bce, Alexander the Great, when marching a detachment of his Macedonian veterans from northern Afghanistan to India, seems to have notched up conquests in Kafiristan (Nuristan), Chitral and Swat, valleys where Himālaya’s western fringes serve as India’s north-west frontier. Along the same frontier but more recently, British expeditions in the 1890s had fought their way into the mountain kingdoms of Hunza and Chitral (both now in Pakistan). Younghusband himself had been involved in these latter-day ventures, refuting Chinese claims to Hunza in the Karakorams as a political agent and reporting on the British occupation of Chitral in the Hindu Kush on a journalistic assignment. As an explorer and collector of military intelligence, he was already famous for exploits beyond India’s frontiers in the Pamirs and Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang). But perhaps Younghusband’s most useful discovery had been made in Chitral where, in 1894, while travelling the length of that valley in the company of a globe-trotting MP, he had found his future patron.

Francis Edward Younghusband, the soldier-explorer responsible for the 1904 invasion of Tibet Captain Francis Younghusband and the Hon. George Nathaniel Curzon MP appeared to have little in common. Younghusband, born into a military family in India, had belied his slight stature by winning cross-country races at school and going straight into the army. … Curzon, on the other hand, the heir to a barony, had garnered prizes at Eton and Balliol and been elected president of the Oxford Union… Few would doubt, least of all Curzon himself, that as a scholar and highly articulate parliamentarian he was destined for the highest office. His appointment in 1899 as the youngest ever viceroy seemed preordained and his six years of forceful rule would generally be reckoned to mark the apogee of the British raj.

But while Curzon winced at Younghusband’s naivety and Younghusband crumpled under Curzon’s interrogation, neither ever doubted their mutual commitment. In the face of criticism over an assignment like Tibet, Curzon could count on Younghusband’s expansionist instincts while Younghusband could bank on Curzon’s unwavering support. Fired by a sense of imperial mission, both believed that ‘Providence or the laws of destiny had called Britain to India for [in Curzon’s words] “the lasting benefit of the human race”.’

The benefit was thought self-evident and amply justified a degree of compulsion.

But British rule in India was constantly under threat, both from within and from without, and nowhere more so than on its long continental frontier in Himālaya. Here, beyond the mountains, another empire, that of tsarist Russia, was invoking Providence and the laws of destiny to justify extending its own lasting benefits to the human race.

It was an old story. Anglo-Russian rivalry in Inner Asia had been smouldering since Napoleonic times… Earlier an Irish cavalryman had called it ‘a great game’ – until, that is, his luck ran out when he was confined in a pit of snakes in Bukhara prior to being executed…

“the Great Game”… entered popular usage… when Kipling adopted the term in his much loved Kim, published in 1901. In that same year it was reported in St Petersburg that envoys from Tibet were being entertained in the Russian capital. They bore gifts and overtures from the young Dalai Lama and were accompanied by a man long resident in Lhasa whom the British identified as Aghvan Dorzhiev.

To those, like Curzon and Younghusband, of a decidedly bullish disposition, this news was as the reddest of red rags. Dorzhiev was portrayed as an unscrupulous adventurer and master of intrigue. It was not his first Russian visit and he was actually a Russian subject. But as a Buriat (Siberian) Mongol, he was a Buddhist by birth and had a genuine interest in Tibetan scholarship. He may have encouraged the Dalai Lama to challenge those of his ministers who favoured good relations with the British, and he may genuinely have believed that Tibetan Buddhism would be safer under the protection of Tsar Nicholas II, among whose subjects were several other Buddhist peoples, than under the newly crowned King Edward VII.

Curzon chose to believe that Dorzhiev had actually drawn up a Russo-Tibetan treaty; Younghusband was convinced that St Petersburg was supplying Lhasa with modern arms; and both men credited reports of a cossack detachment standing by to rush to Tibet’s aid whenever required…

…By November 1903 Younghusband was in Simla being briefed by Curzon. The new expedition was to have British troops as well as more Indian regiments, more and bigger guns, and a supply chain capable of supporting around 2,000 combat troops over vast distances and for several months. But according to a supposedly definitive statement issued by the Cabinet in London, the objectives had changed. The “sole purpose” of the expedition was now that of “obtaining satisfaction” for the recent border transgressions. To this end Younghusband might proceed as far as Gyantse, about halfway to Lhasa. He would withdraw as soon as “reparation is obtained”; no permanent mission was to be left in Tibet and no part of the country occupied… It was simply a punitive action…

The 1903 mission to Khampa Dzong had been shrouded in secrecy, but the 1904 expedition was to be a more public affair. Behind the advancing troops a telegraph line was being hastily erected, postal runners plied daily back to Darjeeling, and officers were allowed to bring along their cameras and sketching materials. Captain Walton was in charge of the natural history collection, a young geologist, Henry Hayden, was on loan from the Geological Survey, and Lieutenant Ryder from the map-making Survey of India. Austine Waddell, an elderly doctor, headed the medical team and, on the strength of previous acquaintance with the Buddhist traditions of Sikkim and Darjeeling, doubled as the expedition’s cultural attaché. Waddell helpfully lists at least five officers who were filing reports or writing articles for the press. In addition, accredited correspondents from The Times, Daily Mail and Reuter’s vied for front-line stories and marvelled at the strange land in which they found themselves. All, like Younghusband, wrote letters home and many, including Dr Waddell, subsequently produced detailed and handsomely illustrated accounts of the whole expedition.

From this mass of reportage, there emerges yet another incentive for the whole undertaking. Besides regulating frontier relations with the Tibetans, exacting satisfaction for their “insults” and countering Lhasa’s supposed overtures to tsarist Russia, the expedition would generate its own dynamic. What Waddell calls the “Land of Mystery”, “the mystic land of the lamas”, was exercising its allure, drawing the intruders onwards. In the thin air it seemed possible to do anything, go anywhere. Dispelling Tibet’s “forbidden” reputation and exploring its romance became ends in themselves.