‘I had a reckless feeling of destiny’: photographer Jill Furmanovsky on Blondie, Bob Marley and rock’s boys’ club | Music

The first rock photograph Jill Furmanovsky ever took was of Paul McCartney, two friends and an elbow. It was 1967 – if her memory serves – and she was 13 years old, whiling away her days outside Abbey Road Studios in the hope of befriending a Beatle. Keeping track of the band’s whereabouts in a fanclub magazine she and tens of thousands others received in the post each month, Furmanovsky read that McCartney had recently moved to St John’s Wood and decided to pay him a visit. “I took the picture outside his house,” she says. “The Beatles were very generous about that sort of thing. It would say: ‘Paul’s moved house’ – they’d virtually give you the address.”

In the half century since that spontaneous snapshot, the photographer has spent her career married to the moshpit. From the smouldering sex appeal of a young Billy Idol (with a kitten), to the Slits, the Clash and Siouxsie Sioux on stage, Furmanovsky’s lens has captured musicians with unfiltered intensity. Seemingly impervious characters elevated to godlike status become humbled in her lens, caught in moments of quotidian intimacy: Roger Waters jokes around with a cupcake during a studio session; Bob Marley, “entirely lovely” as Furmanovsky recalls, reclines in a haze of post-performance weed smoke. “He has a very happy expression on his face, but he was having a lot of problems with the police, so I thought it best to avoid actually showing him smoking – I’ve cut off where the spliff would have been.” A retrospective of her work at Manchester’s central library, guest curated by Noel Gallagher – a frequent Furmanovsky subject – and photo historian Gail Buckland, pays homage to her this month.

Born in Zimbabwe (at that time Rhodesia), Furmanovsky relocated to London with her family when she was 11. “I always felt like a bit of a foreigner,” she says, “but music in the 60s was a cultural movement.” Her introduction came via the TV shows Ready Steady Go! and Top of the Pops: “You would be embarrassed, almost, if your parents were in the room, because Mick Jagger was so sexual.”

When Roger Waters was hired as a junior draughtsman at the architecture firm her father worked at, a 15-year-old Furmanovsky was captivated by stories of a “rather gloomy man” who donned psychedelic shirts and played in a “pop group” called Pink Floyd: “I thought they sounded fabulous!” Her first encounter with the prog pioneers came not long after, sitting on the beer-soaked floor of the Railway pub in West Hampstead – and, in four years’ time Furmanovsky would be on tour with them.

Studying at Central Saint Martins, Furmanovsky threw herself into London’s gig circuit, and soaked up every sound reverberating through the Ralph West student residence in Battersea: “Santana, the Walker Brothers, everything on the Blue Note label; the Rolling Stones, if you were a bad girl.” She discovered an overlap of art and music via Brian Eno, Roxy Music, John Lennon. “Joe Strummer from the Clash was at my college,” she remembers. “Lene Lovich was doing sculpture.” Flitting from gig to gig, she desperately wanted a way in, and in 1971 she attended a Led Zeppelin concert with a pen and paper. “I thought maybe if I did shorthand in a notebook people would think I was a journalist,” she laughs. “I just wanted to get let in.”

When the opportunity presented itself, she seized it. As part of a two-week photography course, Furmanovsky was shooting at the legendary Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park – the backdrop of Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody video, and the Who’s Won’t Get Fooled Again – when someone posed the life-altering question: are you a professional? “I was waiting for it,” she says. When she said yes, she landed a job as the venue’s in-house photographer.

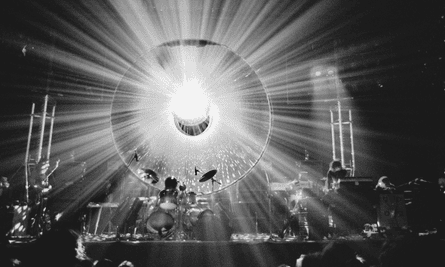

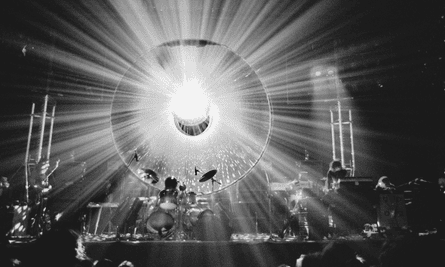

At the same time, she was hired to shoot Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon tour. And so, at 19, Furmanovsky was bundling on to a tour bus with male rock legends 10 years her senior. “I worshipped them through a lens, but it was genuinely very difficult to have a normal conversation,” she admits. She remembers Nick Mason as the easiest to get along with (“drummers are often the most laid back”) and Roger Waters as “a little bit scary. It was very difficult to have a conversation with somebody as gorgeous as David Gilmour, but he was always very smiley. I liked him because he didn’t dress up; he didn’t seem to have much of an ego. They were all rather dishevelled, and just came on stage as they were. Rick Wright was the shyest person I think I’ve met just about anywhere.”

Furmanovsky also describes herself as shy, but says her timidness was always coupled with “a reckless feeling of destiny”. It’s a description that could easily be ascribed to a stereotypical rockstar: the enigmatic introvert who transforms into a force of unstoppable self-assurance on stage. One such reckless move came at a Led Zeppelin concert at Knebworth in 1979, when security were relocating photographers to a far-off vantage point to capture the show. “I didn’t have distance equipment,” she says. “So I hid myself amongst the wives and girlfriends who were being ushered on to the stage and put a camera in my handbag.” Once on stage, she climbed up a gantry for a bird’s eye view and captured her greatest pictures yet. “The camera helped my shyness,” Furmanovsky says. “You magnetise towards things that make you feel like that, and so I was magnetised towards art and music.”

With a few spectacular exceptions, such as Elkie Brooks and Curved Air’s Sonja Kristina (“an icon for the boys”), Furmanovsky’s early career memories are heavy with testosterone: “It was a boys’ club.” Furmanovsky’s first magazine cover was an image of the Who’s Roger Daltrey, which wound up on the front page of British weekly Melody Maker without a credit. After plucking up the courage to confront editor-in-chief Ray Coleman, she received a remorseless response: “You’ll get a credit when you deserve one.”

She attributes the experience to her youthful naivety as well as her gender. Looking back on that male-dominated era, Furmanovsky admires the confidence of artists such as Debbie Harry. “She got it right. Blond and beautiful, but she always had a slightly scary vibe as well – she did a bit of snarling.” Furmanovsky says she still gravitates towards women such as Billie Eilish, who “work against their beauty”, recalling the defiant philosophy of her close friend Chrissie Hynde. “She always said your attitude has to be not ‘fuck me’, but ‘fuck you’.”

Furmanovsky is probably most renowned today for her iconic images of Oasis – from Noel Gallagher commanding a sold-out Maine Road stadium crowd to the band laughing over beers at King’s Cross Snooker Club (now the Hurricane Room) on the day Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997. Liam, she says, is the most typically rock’n’roll person she has ever met: “It’s to do with swagger, and a punk philosophy of ‘I don’t care’. And I think Liam Gallagher does care a lot about the music, but he doesn’t care about his effect on other people, including the band, actually.”

Some of her most pertinent photographs, though, are the ones she has taken of women. She captures Björk’s charismatic curiosity with beautiful softness (“the clearest skin I’ve ever seen on anybody – requires zero retouching of any kind!”), and the endearing eccentricity of a teenage Kate Bush clearly at ease in the photographer’s presence. It’s a rarity even to see male rock legends captured through the female gaze, but when it comes to music’s frontwomen, Furmanovsky’s perspective is even more meaningful. Her portrait of Grace Jones for a 1980 edition of the Face exudes fierce strength and magnetic allure, testament to the photographer’s ability to unveil the complex layers of her subjects. “She reveals you to yourself,” Chic’s Nile Rodgers says in a documentary about Furmanovsky set for release later this year.

“All the great portraits, they’re shot with love and respect for the artists,” adds Noel Gallagher in the film. And Furmanovsky’s own words confirm his sentiment: “I’ve always felt less nervous with musicians than one would think, because they’re just themselves, really. Even the ones that dress up and have this flamboyance are still, in the end, having to plug into their amps and go into rehearsals. There’s some sort of grounding quality to music, I think.”

These everyday rigours share similarities with photography – loading a film is a little like tuning a guitar string – and Furmanovsky ultimately shows us a series of people, not rock stars. As the Face’s former art director Neville Brody says: “Through the honesty of Jill’s work, we are brought closer to the frailty and humanity of celebrity.”

It is these qualities that permeate Furmanovsky’s work even 50 years later, especially in her documentation of artists who died too soon. The exhibition poster is an image of Amy Winehouse reclining against a wall, her smile radiant. It’s a beautiful picture, and a refreshing contrast to the sombre and distressing images of her later life.

“When a great artist passes away, they leave a kind of a trail of light – the vibrations of what they did,” says Furmanovsky. “I always feel pleased if I’ve managed to hand back something of themselves that maybe they didn’t realise they had. And, certainly, for Amy Winehouse, that was the case. I only photographed her that once, and I think I just caught her at a particular moment in time, not realising it, when there was absolute joy in her.”

The first rock photograph Jill Furmanovsky ever took was of Paul McCartney, two friends and an elbow. It was 1967 – if her memory serves – and she was 13 years old, whiling away her days outside Abbey Road Studios in the hope of befriending a Beatle. Keeping track of the band’s whereabouts in a fanclub magazine she and tens of thousands others received in the post each month, Furmanovsky read that McCartney had recently moved to St John’s Wood and decided to pay him a visit. “I took the picture outside his house,” she says. “The Beatles were very generous about that sort of thing. It would say: ‘Paul’s moved house’ – they’d virtually give you the address.”

In the half century since that spontaneous snapshot, the photographer has spent her career married to the moshpit. From the smouldering sex appeal of a young Billy Idol (with a kitten), to the Slits, the Clash and Siouxsie Sioux on stage, Furmanovsky’s lens has captured musicians with unfiltered intensity. Seemingly impervious characters elevated to godlike status become humbled in her lens, caught in moments of quotidian intimacy: Roger Waters jokes around with a cupcake during a studio session; Bob Marley, “entirely lovely” as Furmanovsky recalls, reclines in a haze of post-performance weed smoke. “He has a very happy expression on his face, but he was having a lot of problems with the police, so I thought it best to avoid actually showing him smoking – I’ve cut off where the spliff would have been.” A retrospective of her work at Manchester’s central library, guest curated by Noel Gallagher – a frequent Furmanovsky subject – and photo historian Gail Buckland, pays homage to her this month.

Born in Zimbabwe (at that time Rhodesia), Furmanovsky relocated to London with her family when she was 11. “I always felt like a bit of a foreigner,” she says, “but music in the 60s was a cultural movement.” Her introduction came via the TV shows Ready Steady Go! and Top of the Pops: “You would be embarrassed, almost, if your parents were in the room, because Mick Jagger was so sexual.”

When Roger Waters was hired as a junior draughtsman at the architecture firm her father worked at, a 15-year-old Furmanovsky was captivated by stories of a “rather gloomy man” who donned psychedelic shirts and played in a “pop group” called Pink Floyd: “I thought they sounded fabulous!” Her first encounter with the prog pioneers came not long after, sitting on the beer-soaked floor of the Railway pub in West Hampstead – and, in four years’ time Furmanovsky would be on tour with them.

Studying at Central Saint Martins, Furmanovsky threw herself into London’s gig circuit, and soaked up every sound reverberating through the Ralph West student residence in Battersea: “Santana, the Walker Brothers, everything on the Blue Note label; the Rolling Stones, if you were a bad girl.” She discovered an overlap of art and music via Brian Eno, Roxy Music, John Lennon. “Joe Strummer from the Clash was at my college,” she remembers. “Lene Lovich was doing sculpture.” Flitting from gig to gig, she desperately wanted a way in, and in 1971 she attended a Led Zeppelin concert with a pen and paper. “I thought maybe if I did shorthand in a notebook people would think I was a journalist,” she laughs. “I just wanted to get let in.”

When the opportunity presented itself, she seized it. As part of a two-week photography course, Furmanovsky was shooting at the legendary Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park – the backdrop of Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody video, and the Who’s Won’t Get Fooled Again – when someone posed the life-altering question: are you a professional? “I was waiting for it,” she says. When she said yes, she landed a job as the venue’s in-house photographer.

At the same time, she was hired to shoot Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon tour. And so, at 19, Furmanovsky was bundling on to a tour bus with male rock legends 10 years her senior. “I worshipped them through a lens, but it was genuinely very difficult to have a normal conversation,” she admits. She remembers Nick Mason as the easiest to get along with (“drummers are often the most laid back”) and Roger Waters as “a little bit scary. It was very difficult to have a conversation with somebody as gorgeous as David Gilmour, but he was always very smiley. I liked him because he didn’t dress up; he didn’t seem to have much of an ego. They were all rather dishevelled, and just came on stage as they were. Rick Wright was the shyest person I think I’ve met just about anywhere.”

Furmanovsky also describes herself as shy, but says her timidness was always coupled with “a reckless feeling of destiny”. It’s a description that could easily be ascribed to a stereotypical rockstar: the enigmatic introvert who transforms into a force of unstoppable self-assurance on stage. One such reckless move came at a Led Zeppelin concert at Knebworth in 1979, when security were relocating photographers to a far-off vantage point to capture the show. “I didn’t have distance equipment,” she says. “So I hid myself amongst the wives and girlfriends who were being ushered on to the stage and put a camera in my handbag.” Once on stage, she climbed up a gantry for a bird’s eye view and captured her greatest pictures yet. “The camera helped my shyness,” Furmanovsky says. “You magnetise towards things that make you feel like that, and so I was magnetised towards art and music.”

With a few spectacular exceptions, such as Elkie Brooks and Curved Air’s Sonja Kristina (“an icon for the boys”), Furmanovsky’s early career memories are heavy with testosterone: “It was a boys’ club.” Furmanovsky’s first magazine cover was an image of the Who’s Roger Daltrey, which wound up on the front page of British weekly Melody Maker without a credit. After plucking up the courage to confront editor-in-chief Ray Coleman, she received a remorseless response: “You’ll get a credit when you deserve one.”

She attributes the experience to her youthful naivety as well as her gender. Looking back on that male-dominated era, Furmanovsky admires the confidence of artists such as Debbie Harry. “She got it right. Blond and beautiful, but she always had a slightly scary vibe as well – she did a bit of snarling.” Furmanovsky says she still gravitates towards women such as Billie Eilish, who “work against their beauty”, recalling the defiant philosophy of her close friend Chrissie Hynde. “She always said your attitude has to be not ‘fuck me’, but ‘fuck you’.”

Furmanovsky is probably most renowned today for her iconic images of Oasis – from Noel Gallagher commanding a sold-out Maine Road stadium crowd to the band laughing over beers at King’s Cross Snooker Club (now the Hurricane Room) on the day Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997. Liam, she says, is the most typically rock’n’roll person she has ever met: “It’s to do with swagger, and a punk philosophy of ‘I don’t care’. And I think Liam Gallagher does care a lot about the music, but he doesn’t care about his effect on other people, including the band, actually.”

Some of her most pertinent photographs, though, are the ones she has taken of women. She captures Björk’s charismatic curiosity with beautiful softness (“the clearest skin I’ve ever seen on anybody – requires zero retouching of any kind!”), and the endearing eccentricity of a teenage Kate Bush clearly at ease in the photographer’s presence. It’s a rarity even to see male rock legends captured through the female gaze, but when it comes to music’s frontwomen, Furmanovsky’s perspective is even more meaningful. Her portrait of Grace Jones for a 1980 edition of the Face exudes fierce strength and magnetic allure, testament to the photographer’s ability to unveil the complex layers of her subjects. “She reveals you to yourself,” Chic’s Nile Rodgers says in a documentary about Furmanovsky set for release later this year.

“All the great portraits, they’re shot with love and respect for the artists,” adds Noel Gallagher in the film. And Furmanovsky’s own words confirm his sentiment: “I’ve always felt less nervous with musicians than one would think, because they’re just themselves, really. Even the ones that dress up and have this flamboyance are still, in the end, having to plug into their amps and go into rehearsals. There’s some sort of grounding quality to music, I think.”

These everyday rigours share similarities with photography – loading a film is a little like tuning a guitar string – and Furmanovsky ultimately shows us a series of people, not rock stars. As the Face’s former art director Neville Brody says: “Through the honesty of Jill’s work, we are brought closer to the frailty and humanity of celebrity.”

It is these qualities that permeate Furmanovsky’s work even 50 years later, especially in her documentation of artists who died too soon. The exhibition poster is an image of Amy Winehouse reclining against a wall, her smile radiant. It’s a beautiful picture, and a refreshing contrast to the sombre and distressing images of her later life.

“When a great artist passes away, they leave a kind of a trail of light – the vibrations of what they did,” says Furmanovsky. “I always feel pleased if I’ve managed to hand back something of themselves that maybe they didn’t realise they had. And, certainly, for Amy Winehouse, that was the case. I only photographed her that once, and I think I just caught her at a particular moment in time, not realising it, when there was absolute joy in her.”