‘I’m on the telly sometimes’: actor Mark Bonnar on his quiet anonymity – and his new spy drama | Television & radio

Mark Bonnar is everywhere, but when the actor gets stopped by fans in the street, they struggle to recall where they know him from. “‘I’m sure we’ve met, is your boy Jimmy?’” they ask, assuming he’s a parent they’ve spotted on the school run. In these circumstances, Bonnar – who’s been nominated for five Scottish Baftas and has won one – doesn’t call himself an actor. “What I usually say is, ‘I’m on the telly sometimes,’” he says. Then comes the “Aha!’ moment, and he watches the pieces fall into place, with one (or many) of his characters coming to mind.

Bonnar has built a career out of this quiet ubiquity. He played the corrupt cop Mike Dryden in season two of Line of Duty; the sweary, straight-talking friend to Rob Delaney in Catastrophe; and a detective’s mate with a murky history in BBC’s Shetland. That’s three of the more than 65 performances he’s delivered on screen, and his stage work, which stretches back further and to esteemed places like London’s National Theatre, is similarly prolific.

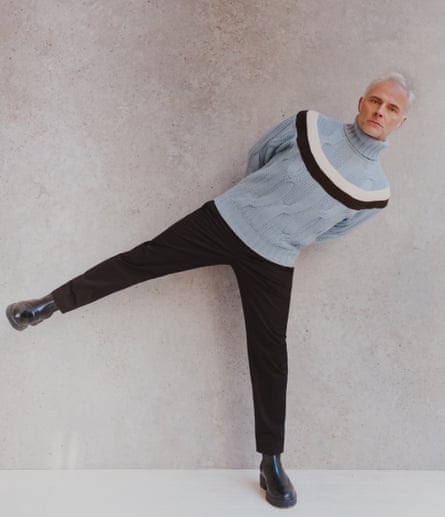

He is seldom front and centre, but has a habit of acting as a vital vertebra in the backbone of his shows. That explains why, when he walks into a mostly empty café in east London on a sharply cold Monday afternoon, barely anybody lifts their head apart from me. He holds out his hand in greeting, grey peacoat over a dark V-neck sweatshirt, hair chrome-silver, and sits down to look over the menu. They’re out of the salads, I say. “That doesn’t matter,” he quips. “We’re Scottish!”

We’re here to discuss Bonnar’s new project: ITV’s Litvinenko, a four-part series that unpacks the investigation into the 2006 poisoning of the Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, an event that dominated British headlines at the time due to its bizarre, spy-thriller nature. The series is not an account of Litvinenko’s life – he only appears in episode one, played by a frosty and compelling David Tennant – but rather a dramatic retelling of the initial investigation that uncovered the culprits behind his death. “It makes you realise what utter clowns [the agents] were,” Bonnar says. “It was just a massive botched job.”

Bonnar plays Detective Superintendent Clive Timmons, the man who oversaw the investigation, and was part of the team responsible for tracing the poison that killed Litvinenko back to its source. Even for an old hat at detective dramas like Bonnar, it stood out: it offered him the rare experience of playing a real person who’d be alive to judge how he did. “It’s quite a nerve-racking thing,” he says now, “because you want them to like it.” The pair first met on Zoom, while Bonnar prepared for the part, and then later on set. (He remembers gawking at how tall Timmons was.) On Zoom, Bonnar peppered Timmons with questions. “I wanted to know all the boring stuff,” he says, squeezing his teabag to the side of his mug. “Where he grew up, what his standout childhood memories were.” He ended up creating a character that dialled in on Timmons’s turns of phrase, and the inflection of his voice.

Bonnar has credited his role in Line of Duty as the part that put him on the map. After the series aired, he was sent several scripts asking him to read for similar characters. But he wasn’t interested in treading similar water. He was drawn to Litvinenko because it offered an alternative. “Dramas these days [are usually about] the broken copper, the alcoholic copper breaking up with his wife. But this was a story about good cops doing good, you know? I thought that was worth telling.”

The scarcity of good cops on screen, I suggest, might be a reflection of the real world – the slew of scandals stemming from the Met, ones that forced Cressida Dick to resign, for example. Timmons told Bonnar: “You have to go into [policing] because you want to do good and help people.” But Bonnar accepts that the public perception of policing is at a low. “It’s difficult, these days especially, to keep things in perspective,” he says. “If you choose to be bombarded by a certain type of bad news, you can easily overwhelm yourself. Social media doesn’t fucking help. It’s important this story is told because you forget that, every single day, there are people who are helping us. That’s the thing about the police. There’s a very select few people that have tarnished it. It used to be an honourable job to do.”

Bonnar has long had what he calls a “low-level fascination” with Russia. It started with their great theatremakers. He played Trofimov in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and appeared opposite Ruth Wilson in Gorky’s Philistines at the National Theatre. It was Howard Davies, the late, longtime director, who cast Bonnar in both productions. “He was the one that had the most first-hand knowledge of the place,” Bonnar reminisces. “He had Russian friends, went over several times, spoke so eloquently about the Russian character. And that bled into a lot of what he did on stage.”

Then, around the time of the Litvinenko poisoning, the dial started to turn for Bonnar. It was a domino effect: the Salisbury poisonings; political interference with the Tory party. “You can’t help but take more of an interest. You’re thinking, ‘What the fuck are they doing?’” he says. “However many millions have been donated to the party by Russians, you just think, ‘What’s going on there? Why are they compromising themselves?’” He calls it “a two-sided coin, because on one hand there’s an incredible, wonderous diversity of culture that emanates from that country. And on the other side it has this tumultuous history. It’s just a huge pity that it’s run by this gangster who seems to have the world under his thumb.”

Bonnar’s paternal grandfather fled Poland at the start of the Second World War. “The story goes that his brother was put in a concentration camp and my grandad and his mate decided to up sticks and walk to Yugoslavia,” he says. His knowledge of the events is scanty – his father rarely discussed it – but to the best of his knowledge his grandfather landed in Edinburgh, joined the RAF and fought in the war. A few years after it ended, Bonnar’s father, Stanley – now an artist and philanthropist – was born. It was when his dad was a teenager, studying sculpture at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee, that he met Rosi, Bonnar’s mother. Bonnar was born when Stanley was 19 and Rosi was 20, an art school baby “doomed from the beginning”.

The family moved to Glenrothes after Stanley graduated, and Stanley started a long-running career as a new town artist, creating council-funded stone sculptures. His most famous, of a family of hippos in Glenrothes, still stands today, and inspired a documentary Bonnar made with him for the BBC called Meet You at the Hippos. “I don’t really remember Glenrothes,” Bonnar says. The family left just after he started school, moving to East Kilbride, just outside Glasgow, and staying there for two years. “I just remember it being hard, you’d have to make friends every time.” Most of his adolescence was spent in a rural village called Stonehouse, where his father created concrete elephants.

There are bourgeois connotations of being the child of an artist, but after Stanley had made many of his most famous works, the Bonnar family moved to Edinburgh and started from scratch again. “I remember it being quite difficult moving to secondary school,” Bonnar says. “I was in a new city where I knew absolutely nobody. You just have to survive on your wits, really.” Meanwhile, during a bout of creative unemployment, Stanley was a milkman and Rosi drove a play bus. (She later moved into social work.)

Bonnar once said that class position is “in your head”, and that although he has become a well-known actor, he still considers himself working class. “I always kind of felt that’s what I was because that’s where I was brought up, you know? But several people throughout my life have gone: ‘What did your ma and dad do?’ I’d say my dad was an artist and my mum was a social worker.” They’d tell him: “‘You’re not fucking working class.’”

“It depends on your definition,” he clarifies now. “To me I was brought up on a council estate most of my life. You used to be able to separate working class from being socialist when I was young. I’m still a socialist even though it’s a word they’ve tried to drown. I think in its essence and its soul, it’s a good thing. There’s no bad thing in wanting the best for everyone. There’s a lot of people to blame for the lack of whatever it is that the poor folk don’t have now, and we know where they’re fucking sitting.”

Bonnar feels the same about his Scottish heritage. “I’ve almost been down here longer than I lived up there. That’s a really weird thought,” he says. “I never say I’m proud to be Scottish, because that phrase doesn’t make any fucking sense. As Bill Hicks used to say, ‘My mum and dad fucked there.’ But I think there’s something that’s inside you, part of your physicality, that is specific to the place you’re born. Scotland is an amazing place, and it’s my home.” Will he move back? He shakes his head. “I don’t think it will ever happen, but I’m determined to take the kids and go and show them where I’m from.”

He’s since moved to Hertfordshire, setting up a quiet life with his wife, the actor Lucy Gaskell, and their two children. “There’s a shorthand [we share],” he says of his marriage. He’s got someone who knows the semantics of the self-taped audition. “I mean, I’ve been away working for almost the whole year. The logistical support and emotional support she provides, it’s monumental. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for her.” There are few gripes at home, he says, apart from his sleeping pattern. “I’ve always been a deep sleeper, much to my wife’s chagrin,” he says, bashfully. “I snore like a buffalo, so I’ll often wake up with a punch in the ribs!”

Bonnar returned to Edinburgh earlier this year to shoot The Rig, a new, supernatural series set on an oil rig debuting in early 2023. It’s the first Amazon Prime original series to be shot entirely in Scotland.

After The Rig, 2023 looks even busier: a part in the second season of the television series World on Fire, starring Lesley Manville, and a collaboration with Ridley Scott in his big-budget retelling of the story of Napoleon. Working with Scott was “magical”, he says. “I was tongue-tied every time he came up to me.” He breaks into a perfect replica of the director’s gruff English accent to recreate a moment on set: “‘Other people wouldn’t do it like this, you know? Two cameras, it will take a week to shoot this scene. If you have five cameras, you can get it done in half a day. We’ll be done by halfpast 12!’” Bonnar’s in fits of laughter, half at the absurd genius of Scott as a director, and half at the pinch-me idea of working with him at all.

“I want to work with good people,” he says. “I’m especially proud to have been part of Litvinenko for that reason, because it tells a good story about good people who have stood up against tyranny. And as a human, there’s no greater thing you can do.”

Litvinenko is available to watch now on ITVX

Fashion editor Helen Seamons, fashion assistant Roz Donoghue, grooming Juliana Sergot

Mark Bonnar is everywhere, but when the actor gets stopped by fans in the street, they struggle to recall where they know him from. “‘I’m sure we’ve met, is your boy Jimmy?’” they ask, assuming he’s a parent they’ve spotted on the school run. In these circumstances, Bonnar – who’s been nominated for five Scottish Baftas and has won one – doesn’t call himself an actor. “What I usually say is, ‘I’m on the telly sometimes,’” he says. Then comes the “Aha!’ moment, and he watches the pieces fall into place, with one (or many) of his characters coming to mind.

Bonnar has built a career out of this quiet ubiquity. He played the corrupt cop Mike Dryden in season two of Line of Duty; the sweary, straight-talking friend to Rob Delaney in Catastrophe; and a detective’s mate with a murky history in BBC’s Shetland. That’s three of the more than 65 performances he’s delivered on screen, and his stage work, which stretches back further and to esteemed places like London’s National Theatre, is similarly prolific.

He is seldom front and centre, but has a habit of acting as a vital vertebra in the backbone of his shows. That explains why, when he walks into a mostly empty café in east London on a sharply cold Monday afternoon, barely anybody lifts their head apart from me. He holds out his hand in greeting, grey peacoat over a dark V-neck sweatshirt, hair chrome-silver, and sits down to look over the menu. They’re out of the salads, I say. “That doesn’t matter,” he quips. “We’re Scottish!”

We’re here to discuss Bonnar’s new project: ITV’s Litvinenko, a four-part series that unpacks the investigation into the 2006 poisoning of the Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, an event that dominated British headlines at the time due to its bizarre, spy-thriller nature. The series is not an account of Litvinenko’s life – he only appears in episode one, played by a frosty and compelling David Tennant – but rather a dramatic retelling of the initial investigation that uncovered the culprits behind his death. “It makes you realise what utter clowns [the agents] were,” Bonnar says. “It was just a massive botched job.”

Bonnar plays Detective Superintendent Clive Timmons, the man who oversaw the investigation, and was part of the team responsible for tracing the poison that killed Litvinenko back to its source. Even for an old hat at detective dramas like Bonnar, it stood out: it offered him the rare experience of playing a real person who’d be alive to judge how he did. “It’s quite a nerve-racking thing,” he says now, “because you want them to like it.” The pair first met on Zoom, while Bonnar prepared for the part, and then later on set. (He remembers gawking at how tall Timmons was.) On Zoom, Bonnar peppered Timmons with questions. “I wanted to know all the boring stuff,” he says, squeezing his teabag to the side of his mug. “Where he grew up, what his standout childhood memories were.” He ended up creating a character that dialled in on Timmons’s turns of phrase, and the inflection of his voice.

Bonnar has credited his role in Line of Duty as the part that put him on the map. After the series aired, he was sent several scripts asking him to read for similar characters. But he wasn’t interested in treading similar water. He was drawn to Litvinenko because it offered an alternative. “Dramas these days [are usually about] the broken copper, the alcoholic copper breaking up with his wife. But this was a story about good cops doing good, you know? I thought that was worth telling.”

The scarcity of good cops on screen, I suggest, might be a reflection of the real world – the slew of scandals stemming from the Met, ones that forced Cressida Dick to resign, for example. Timmons told Bonnar: “You have to go into [policing] because you want to do good and help people.” But Bonnar accepts that the public perception of policing is at a low. “It’s difficult, these days especially, to keep things in perspective,” he says. “If you choose to be bombarded by a certain type of bad news, you can easily overwhelm yourself. Social media doesn’t fucking help. It’s important this story is told because you forget that, every single day, there are people who are helping us. That’s the thing about the police. There’s a very select few people that have tarnished it. It used to be an honourable job to do.”

Bonnar has long had what he calls a “low-level fascination” with Russia. It started with their great theatremakers. He played Trofimov in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and appeared opposite Ruth Wilson in Gorky’s Philistines at the National Theatre. It was Howard Davies, the late, longtime director, who cast Bonnar in both productions. “He was the one that had the most first-hand knowledge of the place,” Bonnar reminisces. “He had Russian friends, went over several times, spoke so eloquently about the Russian character. And that bled into a lot of what he did on stage.”

Then, around the time of the Litvinenko poisoning, the dial started to turn for Bonnar. It was a domino effect: the Salisbury poisonings; political interference with the Tory party. “You can’t help but take more of an interest. You’re thinking, ‘What the fuck are they doing?’” he says. “However many millions have been donated to the party by Russians, you just think, ‘What’s going on there? Why are they compromising themselves?’” He calls it “a two-sided coin, because on one hand there’s an incredible, wonderous diversity of culture that emanates from that country. And on the other side it has this tumultuous history. It’s just a huge pity that it’s run by this gangster who seems to have the world under his thumb.”

Bonnar’s paternal grandfather fled Poland at the start of the Second World War. “The story goes that his brother was put in a concentration camp and my grandad and his mate decided to up sticks and walk to Yugoslavia,” he says. His knowledge of the events is scanty – his father rarely discussed it – but to the best of his knowledge his grandfather landed in Edinburgh, joined the RAF and fought in the war. A few years after it ended, Bonnar’s father, Stanley – now an artist and philanthropist – was born. It was when his dad was a teenager, studying sculpture at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee, that he met Rosi, Bonnar’s mother. Bonnar was born when Stanley was 19 and Rosi was 20, an art school baby “doomed from the beginning”.

The family moved to Glenrothes after Stanley graduated, and Stanley started a long-running career as a new town artist, creating council-funded stone sculptures. His most famous, of a family of hippos in Glenrothes, still stands today, and inspired a documentary Bonnar made with him for the BBC called Meet You at the Hippos. “I don’t really remember Glenrothes,” Bonnar says. The family left just after he started school, moving to East Kilbride, just outside Glasgow, and staying there for two years. “I just remember it being hard, you’d have to make friends every time.” Most of his adolescence was spent in a rural village called Stonehouse, where his father created concrete elephants.

There are bourgeois connotations of being the child of an artist, but after Stanley had made many of his most famous works, the Bonnar family moved to Edinburgh and started from scratch again. “I remember it being quite difficult moving to secondary school,” Bonnar says. “I was in a new city where I knew absolutely nobody. You just have to survive on your wits, really.” Meanwhile, during a bout of creative unemployment, Stanley was a milkman and Rosi drove a play bus. (She later moved into social work.)

Bonnar once said that class position is “in your head”, and that although he has become a well-known actor, he still considers himself working class. “I always kind of felt that’s what I was because that’s where I was brought up, you know? But several people throughout my life have gone: ‘What did your ma and dad do?’ I’d say my dad was an artist and my mum was a social worker.” They’d tell him: “‘You’re not fucking working class.’”

“It depends on your definition,” he clarifies now. “To me I was brought up on a council estate most of my life. You used to be able to separate working class from being socialist when I was young. I’m still a socialist even though it’s a word they’ve tried to drown. I think in its essence and its soul, it’s a good thing. There’s no bad thing in wanting the best for everyone. There’s a lot of people to blame for the lack of whatever it is that the poor folk don’t have now, and we know where they’re fucking sitting.”

Bonnar feels the same about his Scottish heritage. “I’ve almost been down here longer than I lived up there. That’s a really weird thought,” he says. “I never say I’m proud to be Scottish, because that phrase doesn’t make any fucking sense. As Bill Hicks used to say, ‘My mum and dad fucked there.’ But I think there’s something that’s inside you, part of your physicality, that is specific to the place you’re born. Scotland is an amazing place, and it’s my home.” Will he move back? He shakes his head. “I don’t think it will ever happen, but I’m determined to take the kids and go and show them where I’m from.”

He’s since moved to Hertfordshire, setting up a quiet life with his wife, the actor Lucy Gaskell, and their two children. “There’s a shorthand [we share],” he says of his marriage. He’s got someone who knows the semantics of the self-taped audition. “I mean, I’ve been away working for almost the whole year. The logistical support and emotional support she provides, it’s monumental. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for her.” There are few gripes at home, he says, apart from his sleeping pattern. “I’ve always been a deep sleeper, much to my wife’s chagrin,” he says, bashfully. “I snore like a buffalo, so I’ll often wake up with a punch in the ribs!”

Bonnar returned to Edinburgh earlier this year to shoot The Rig, a new, supernatural series set on an oil rig debuting in early 2023. It’s the first Amazon Prime original series to be shot entirely in Scotland.

After The Rig, 2023 looks even busier: a part in the second season of the television series World on Fire, starring Lesley Manville, and a collaboration with Ridley Scott in his big-budget retelling of the story of Napoleon. Working with Scott was “magical”, he says. “I was tongue-tied every time he came up to me.” He breaks into a perfect replica of the director’s gruff English accent to recreate a moment on set: “‘Other people wouldn’t do it like this, you know? Two cameras, it will take a week to shoot this scene. If you have five cameras, you can get it done in half a day. We’ll be done by halfpast 12!’” Bonnar’s in fits of laughter, half at the absurd genius of Scott as a director, and half at the pinch-me idea of working with him at all.

“I want to work with good people,” he says. “I’m especially proud to have been part of Litvinenko for that reason, because it tells a good story about good people who have stood up against tyranny. And as a human, there’s no greater thing you can do.”

Litvinenko is available to watch now on ITVX

Fashion editor Helen Seamons, fashion assistant Roz Donoghue, grooming Juliana Sergot