Inside Fanatics’ wild bet to become the Amazon of sports

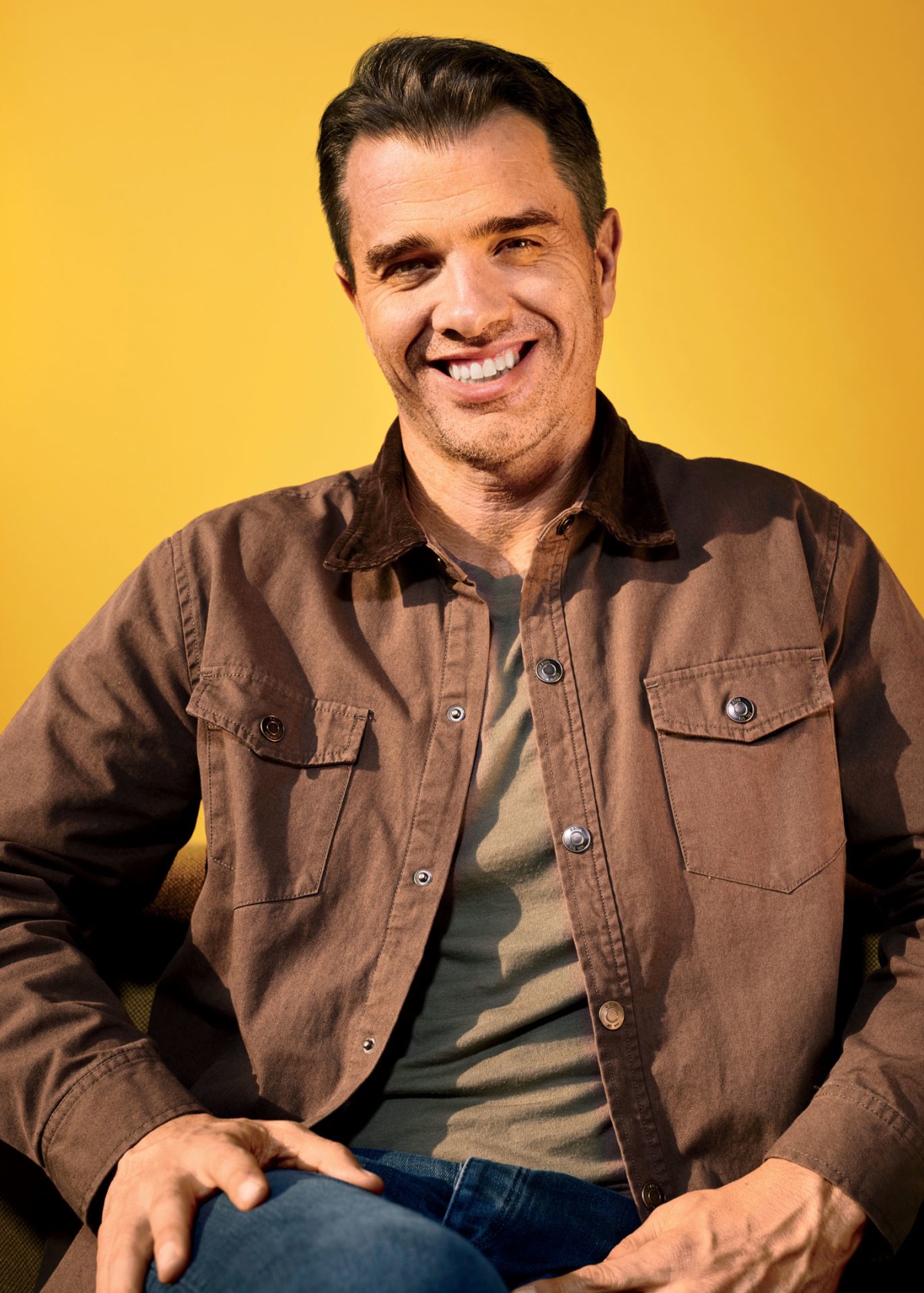

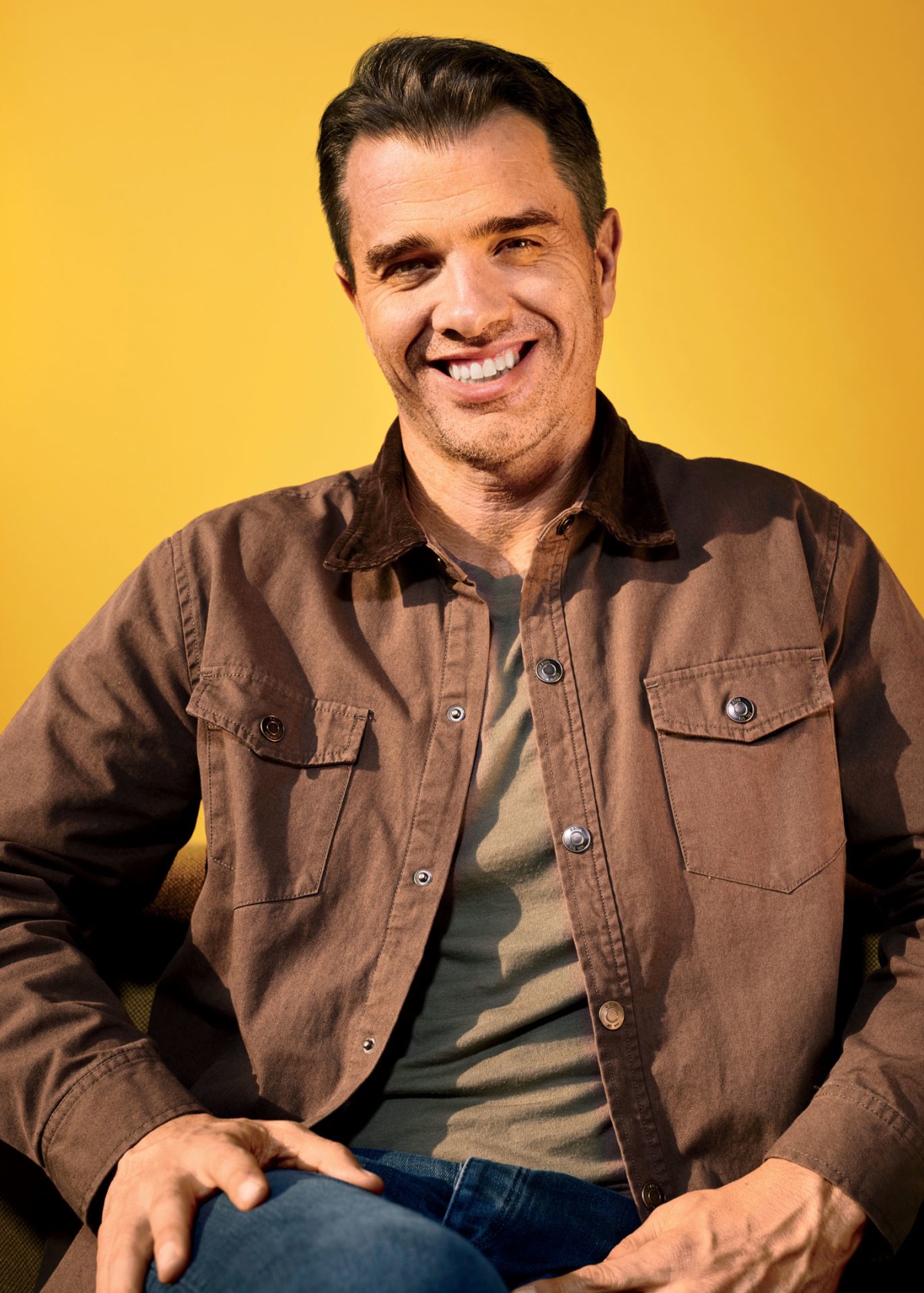

Michael Rubin, the billionaire CEO of Fanatics, splits his time between three primary residences—four, if you count the new $70 million pied-à-terre in the Hollywood Hills, overlooking downtown Los Angeles. Tuesdays through Thursdays are reserved for his penthouse in New York’s Greenwich Village, not far from the main Fanatics headquarters. Thursday nights, it’s back to Philadelphia, where he grew up, and where his eldest daughter is finishing high school—unless it’s summer, in which case Rubin decamps to his 8,000-square-foot modernist mansion in Bridgehampton, on the South Fork of Long Island, New York.

Commuting is no fun for anyone. For an executive with a work and social calendar resembling a Pollock painting, traffic and other forms of quotidian delay are an even bigger menace, and Rubin eschews earthbound travel unless absolutely necessary, preferring to fly everywhere he goes, whether by private jet or on Fanatics’ “two helis,” as he calls them. “I’m in the air so much,” he told me this fall. “Every which way, I’d die without it.”

On the second Saturday in September, Rubin took his jet from Philadelphia to a private air hangar near the Dallas Fort Worth airport and then climbed into a rented Tahoe, which carried him to the local Fanatics office. He then reboarded the SUV and drove a few more miles north, to the site of the Dallas Card Show. Founded a decade ago, as a modest, 10-table swap meet, the card show is today one of the most important events for the multibillion-dollar sports collectibles industry—a sector that Fanatics, valued at $31 billion and already the single biggest manufacturer and distributor of sports fan apparel in the U.S., is intent on dominating.

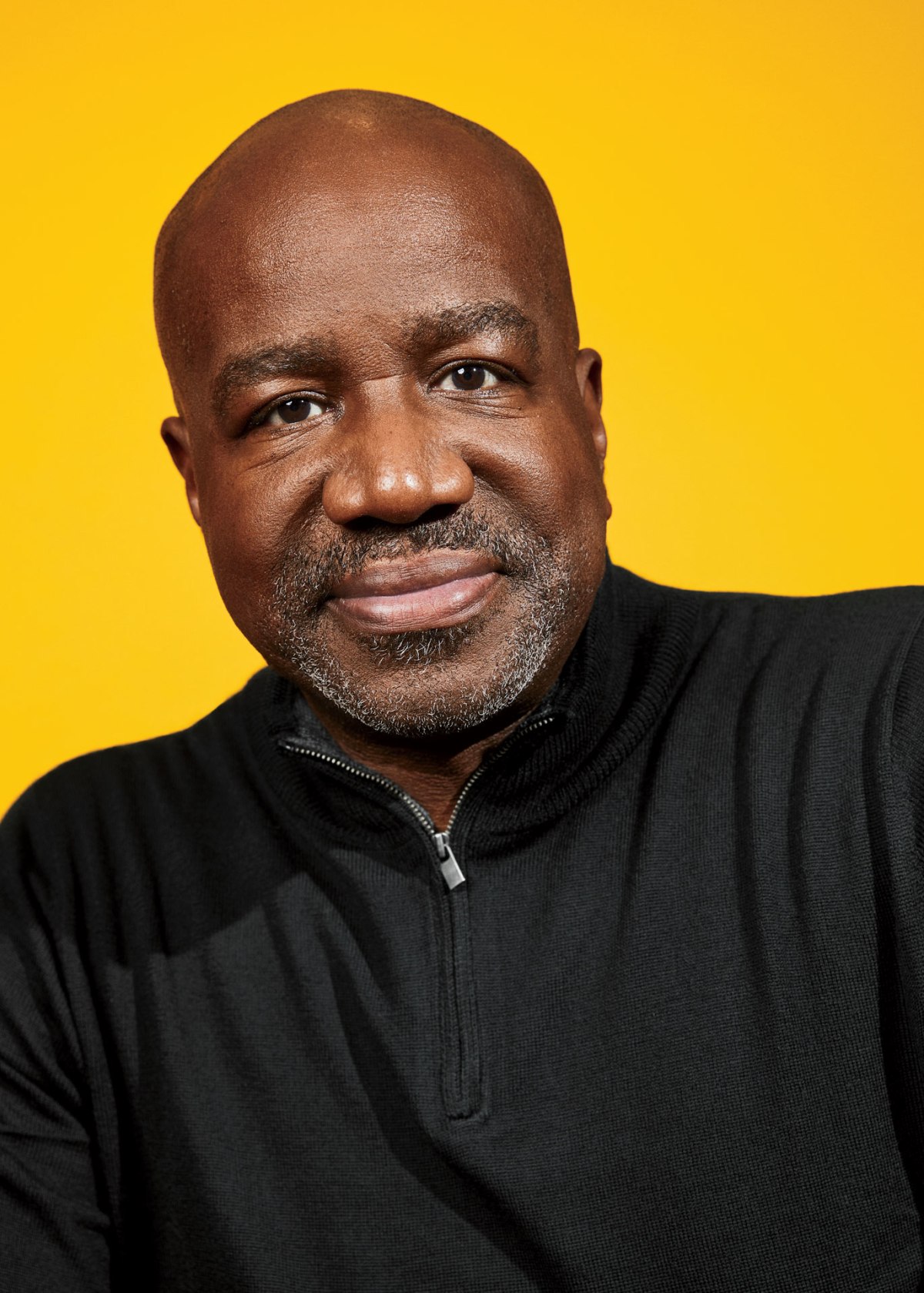

Rubin waded into the scrum of the conference hall tentatively, his hands jammed into the pockets of his black jeans. Although he’s been celestially wealthy since 2011, when he sold his first company, GSI Commerce, to eBay, for $2.4 billion, Rubin has an unassuming presence for a business mogul—he’s slender, 5-foot-9 in sneakers, with brown hair that he wears in a kind of modified crew cut. His most defining characteristic is his eyes, which are close-set and densely lashed. Murmurs and nods followed him across the floor, as did a camera crew assigned to capture footage for Fanatics. “I don’t think of myself as a celebrity,” he said. “But I do get a fair amount of attention from young guys, let’s call it 20 to 30 years old, because they think, ‘Okay, yeah, I want to be like that guy in business.’”

A few yards in, the first selfie-seeker materialized. He was wearing a Cincinnati Reds jersey and an oversize plastic baseball helmet. “Love what you do,” Baseball Helmet Man said. “Thanks, brother,” Rubin replied, smiling up into the iPhone lens. More murmurs, more nods. One selfie begets another, and another, ad infinitum. Rubin posed dutifully for them all. Would he autograph a hundred-dollar bill? He would, gladly. Would he talk about the Braves’ World Series chances? He would, at exhaustive length. Would he accept a résumé from a college graduate seeking work at Fanatics? He would, with a caveat: “I’ll pass this along to the right people and see what they can do,” he said. “I’ll try, brother.”

Rubin, despite his protestations to the contrary, has achieved an extraordinary degree of mainstream stardom in recent months—partly owing to the vertiginous growth of Fanatics (an estimated $8 billion in revenue in 2023 alone) and largely due to his friendships with nearly every big name in the worlds of hip-hop and professional sports. James Harden and Joel Embiid, the NBA legends, are good pals, as is the rapper Meek Mill, whom Rubin successfully lobbied to have released from jail in 2018 and later pardoned on the original bogus gun charges. When Rubin threw a Fourth of July “white party” at his estate on the Hamptons, earlier this year, Meek and Harden showed up, as did Justin Bieber, Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Tom Brady, and Leonardo DiCaprio. All were clad in white. Usher played a set, and Kim Kardashian knocked back 11 shots. TMZ called the bash a “who’s who of fame.”

But the attendees of the Dallas Card Show were far more interested in different developments. Fanatics, known for making and selling licensed apparel for professional and college sports teams, had acquired Topps, the trading card company, in 2022. It had also recently moved into online sports betting, launched a live shopping app, and acquired PWCC Marketplace, a popular auction and sales site for trading cards and sports memorabilia. Depending on your point of view, these business moves either made Rubin a heedless monopolist whose core products were beginning to suffer for sake of growth or the benevolent king of the most powerful empire in sports fandom.

The previous night, in the kind of flex he specializes in, Rubin had invited his friends Odell Beckham Jr. and Derek Jeter to a studio at Fanatics HQ in New York to open boxes of Topps cards—a “break,” as industry insiders call it. Halfway through the livestream, he’d FaceTimed a different buddy, Tom Brady, who showed off a pile of jerseys from various points in his career. “It’s really all one customer base,” Rubin told me in Texas. “Look around the room. We know everyone here is into trading cards, but how many also buy licensed apparel? And how many bet on sports?” He caught himself. “Well, it’s not legal in Texas yet, so how many bet on sports illegally? Probably a lot. Again: It’s one customer base, and we can reach them all.”

Yet Rubin allowed that he was “smart enough to know the shit I don’t know,” and a major part of the Topps acquisition—and deals with various leagues and players’ unions for the likenesses of athletes from the NFL, MLB, and NBA—had involved schooling himself in the intricacies of the collectible-card market. “It’s why I come to events like this,” he said. “It’s important for me to hear what we’re getting right, but I like getting beat up by people too. When they tell me things we’ve managed to fuck up or get wrong, it doesn’t bother me. You have to always be learning, or you’re dead.”

He stopped at a booth rented by Roadshow Cards, a collectibles business with stores in Texas, New York, Kentucky, and California. “Be honest with me,” Rubin said to Cody Crim, a proprietor. “What could we be doing better?” Crim exchanged a glance with his colleagues. How transparent, exactly, was he supposed to be? “You guys are already a breath of fresh air,” he began, tentatively. “Like, the last CEO”—of the preacquisition Topps—“I never saw him in an office setting, let alone at a place like this. It’s good just to talk to you. It’s helpful.”

“I told you, you could be honest, brother,” Rubin said.

After what appeared to be an agonizing—and rapid—series of mental calculations, Crim relented. Sometimes, he allowed, major Topps products weren’t hitting his stores on the day of release. This was a problem, since a savvy collector might attempt to find the cards elsewhere. “Okay,” Rubin nodded. “Product on release day. Got it. We’re on it. What else?”

I was book stupid. I really was,” Rubin told me one afternoon this fall, at his brick-lined office on the eighth floor of Fanatics’ headquarters on New York’s Morton Street. “I got an 800 on my SATs—800 combined, not just on one half. I hated school. But I believed I could outhustle anyone.”

“Michael’s not as educated as some,” suggested a communications staffer, who was seated to his boss’s left, with his back to the Hudson River. “But he’s intellectually curious.”

“He’s calling me a fucking idiot,” Rubin said.

“No. Intellectually curious,” the staffer said. “He asks questions.”

Rubin could agree with this. “Always,” he said.

The tale of Rubin’s ascent has been frequently told: the ski-tuning shop he started out of his parents’ basement as a teen in the suburbs of Philly, which evolved into selling overstock ski equipment at malls, and then overstock sports apparel in general; his early departure from Villanova with a GPA south of 2.0. Rubin then founded Global Sports Incorporated, which included a women’s footwear brand. When he was 23, he moved into e-commerce management and launched GSI Commerce.

GSI was a product of the early internet era, when corporations such as Toys “R” Us, Estée Lauder, and Bed Bath & Beyond sold nearly all their products through brick-and-mortar storefronts. Rubin’s pitch was straightforward: He and his team would build and manage the brands’ e-commerce sites while also handling shipping and fulfillment, allowing them to reach a vast new online audience. Soon, hundreds of millions of dollars in transactions were being shunted through GSI-run sites.

As the company grew, so did Rubin’s forays into licensed sporting goods: In 2002, he won the right to sell Nascar-branded gear online, and in 2005, he reached a similar deal with the NHL. The NBA and NFL followed. Rubin told me that by 2011, the year GSI was acquired by eBay, the sports vertical of the company alone was seeing revenue north of $250 million annually. Not enough. What about college sports? “We had a strong foothold with professional sports, but not with, like, the NCAA. But there was this company in Florida that had been successful there, and so I flew down to see them.” The company, a regional retail chain that sold sports fan gear and had just moved into e-commerce, was called Fanatics. Rubin bought it more or less on the spot, for $277 million.

The brand was initially folded into the deal with eBay, but the auction site had little use for it: eBay brass didn’t like the idea of competing with its own merchants. Shortly after the acquisition closed, Rubin arranged to buy Fanatics back, at a nearly $90 million markup.

Again, as he had in the early days of GSI, Rubin saw opportunity with Fanatics. “My original thought was like, ‘Look, there’s this little company in Seattle called Amazon and they kind of kill everybody. And there’s this other company in China called Alibaba. They’re killing everybody else.’” Rubin was sure that Fanatics could attain something close to that level of success by focusing on selling to sports fans alone—surveys regularly show approximately 70% of Americans count themselves as committed fans—but not in its current form. “We didn’t have a great point of differentiation,” Rubin said. “And I had the view that we’d be dead if we didn’t completely transform the business. By the way, I was right.”

That reinvention ultimately hinged on how licensed fan gear was made and sold. For years, sports leagues outsourced manufacturing to various brands and their network of factories around the globe, and GSI sold it online. But there were some drawbacks to the setup, the most obvious being the speed at which apparel reached fans. Factories could take as long as nine months to make a line of jerseys, at which point a player might have retired or been sent back to the minors. Leagues frequently found themselves awash in jerseys that no one wanted (or empty-handed in the event an underdog team or player had a breakout season).

“Let’s just make them ourselves,” Rubin remembers thinking. Manufacturing wasn’t quantum physics; it did require capital, but SoftBank and Silver Lake, among other investors, were happy to provide it. Beginning in 2012, Rubin requested meetings with the heads of the NFL and NBA, and pitched them on his vision: Forget the network of factories. I’ll make the apparel for you, and I’ll make it quickly, in the space of weeks, with endless amounts of customization. If Brady had another record-setting season, Fanatics could have nine variants of his jersey on sale by Super Bowl Sunday. If one day, Taylor Swift fans happened to drive up sales of a certain Kansas City Chiefs jersey by 400%, Fanatics would be ready.

“I basically spent two years explaining to commissioners how they could build their own, better direct-to-consumer business,” Rubin said. “I said, ‘Your retail business will get bigger, you’ll get a bigger percentage of the sales, and we’ll provide you with all this customer data that you can use.’” No one ever said no, Rubin recalled: “They just said yes slowly.”

Passion Points

How Fanatics is expanding its empire to touch all parts of sports fans’ lives

Magic Johnson, a longtime friend of Rubin’s and a former member of the Fanatics board (Johnson left upon taking an ownership stake in the Washington Commanders, citing a conflict of interest), said that his friend can be exceptionally persistent. “He’s relentless,” Johnson said. “It’s constantly, ‘What’s next, what’s next, what’s next?’” Johnson added: “You absolutely never want to underestimate Michael.”

In 2018, the NFL, Nike, and Fanatics announced a three-way, 10-year deal for Fanatics to design and manufacture all official Nike fan apparel for the league; Fanatics reached a similar arrangement with the MLB the same year. (Both lines launched in 2020, meaning that if you’ve purchased a piece of Nike-branded NFL or MLB clothing in the past three years, you were actually purchasing a Fanatics-made product.) Rubin has since acquired the rights to make gear for hundreds of colleges and universities and the best baseball team in Japan, the Tokyo Giants. In March, Fanatics secured a licensing deal for the NHL’s on-ice uniforms, starting with the 2024–2025 season, and through the 2016 purchase of the U.K. sports-merchandise company Kitbag, the e-commerce rights to Manchester United and other major European soccer clubs.

The Kitbag acquisition is a good example of the Fanatics ethos under Rubin: Where you can’t elbow a competitor out of the way, you might as well swallow them whole. The company pulled a similar trick last year with the sports-apparel brand Mitchell & Ness, which Fanatics purchased for a reported $250 million in conjunction with a group of investors that included Maverick Carter, Meek Mill, and Jay-Z. Add the company’s 2017 acquisition of VF Licensed Sports Group, including apparel brand and MLB uniform maker Majestic, and its 2018 minority stake in Lids, the ball-cap retailer, and there are vanishingly few ways to buy sports apparel in 2023 that do not involve Fanatics.

Or, for that matter, to be a sports fan or viewer, full stop: When I spoke to Orlando Ashford, the chief people officer of Fanatics, he mentioned that the company had arranged to handle fulfillment of all sports-related wishes for the Make-A-Wish Foundation, the 43-year-old nonprofit. Fanatics is donating $10 million for the privilege and is not making any money from the arrangement. Yet it’s hardly a stealth venture. In the media, the initiative is now referred to by its full name: Fanatics Make-A-Wish.

Rubin likes to describe the growth of Fanatics as a two-stage proposition: “First decade,” he told me, “we got everything set up. Now, in the second decade, we’re really ready to grow.” He predicted that in coming years, Fanatics would expand to “many times” its current size.

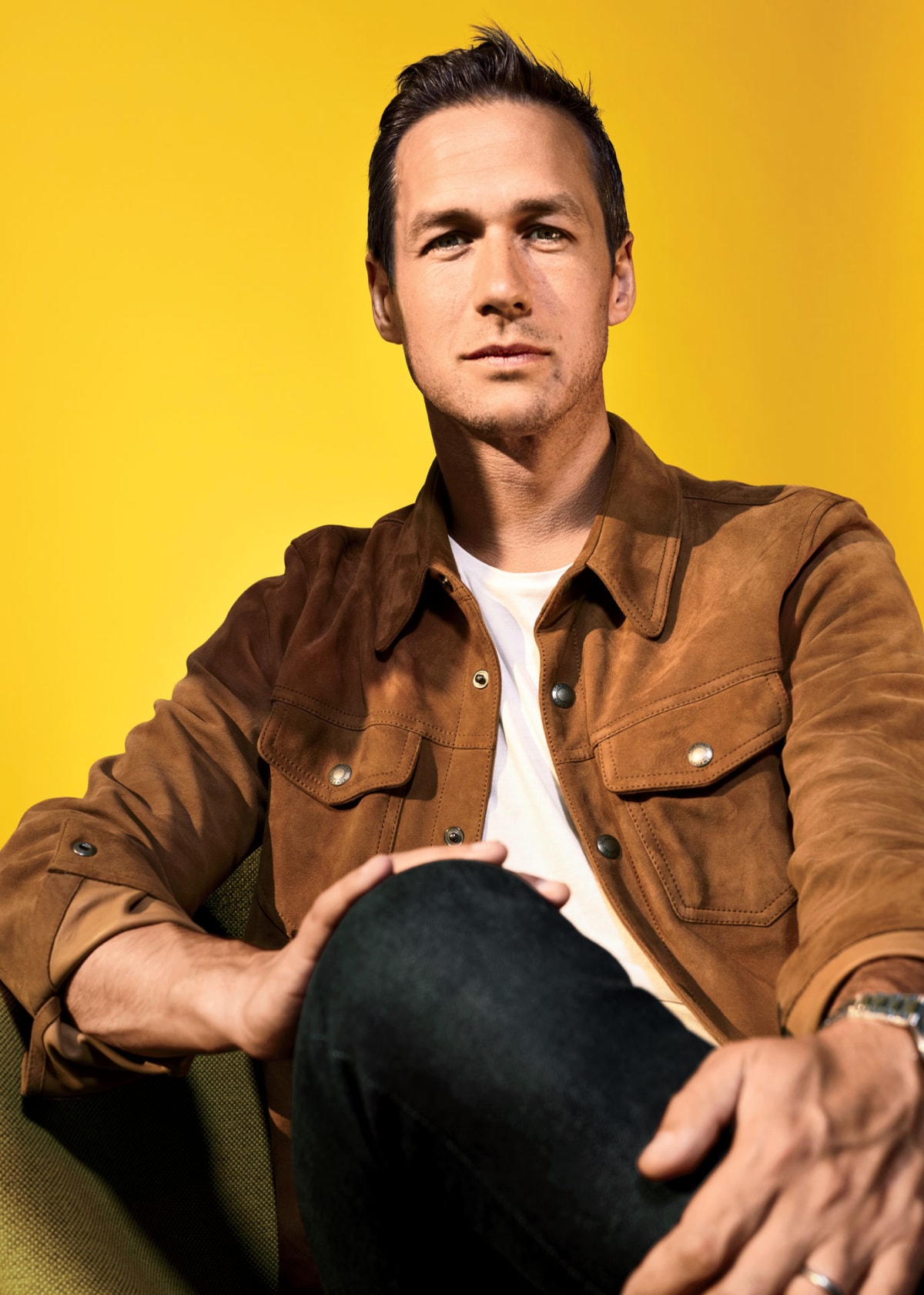

Those closest to Rubin see little reason to doubt him. “I think Fanatics will be the Amazon of the sports world, I really do,” says Rich Kleiman, the longtime manager of NBA superstar Kevin Durant and the CEO of the sports and entertainment company Boardroom. Just as Jeff Bezos merely started with a bookstore, “that’s what I see Michael doing for sports,” says Kleiman, “which you’ve gotta remember is the most influential and popular force in society right now.”

Of course, the bigger a company grows, the more unwieldy it becomes. And while Rubin once had his hands on nearly every decision Fanatics made, that’s no longer possible, given its gargantuan footprint—18,000 employees in dozens of states and across 15 countries, not counting 5,000 Lids staff. Rubin has adjusted by hiring senior execs from FanDuel, Snap, Dick Clark Productions, and elsewhere to run the ever-multiplying number of Fanatics verticals. “My thing is to be involved where I can add value, and not to get involved at all where I won’t,” Rubin told me.

In December 2022, Fanatics closed on a $700 million investment round led by Clearlake Capital, driving its valuation up fivefold from $6.2 billion three years prior. The money could help cover the cost of all the sundry investments—some of which have proved shorter-lived than others. In May, for example, Rubin announced to staff that Fanatics was selling its 60% stake in the NFT firm Candy Digital, citing the “imploding NFT market.”

Fanatics is pushing into other challenging spaces. Sports betting, for example, is dominated by deeply entrenched players. Matt King, the former CEO of FanDuel and now Fanatics’ betting and gaming chief, told me the strategy of early entrants had been to “spend massive amounts on advertising to acquire customers they hoped to monetize later.” Fanatics would not be able to match that advertising blitz, he went on, but nor would it want to: “We think we can adopt a strategy that really leads with product, leads with loyalty and rewards, and lets virality and word of mouth play their roles.” Make the experience of sports betting more intuitive, and disgruntled FanDuel users will come to you.

This fall, Scot McClintic, chief product officer of Fanatics Betting and Gaming, gave me a virtual tour of the Fanatics Sportsbook app, which is currently available for use in five states: Massachusetts, Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee. (In August, Fanatics gobbled up the American arm of the Australian gambling operation PointsBet for $225 million, which has now added eight more states.) There is no browser-based Fanatics Sportsbook, he explained; all the design team’s energy had gone into crafting a better mobile-based experience. But the most striking difference could be the Fanatics Sportsbook’s integration into the larger company ecosystem: On the app, customers can gamble with cash or FanCash, reward points that are generated by wagering or buying apparel and other merchandise on the Fanatics site. The more you wager or buy from Fanatics, the more free bets you’re able to place. “I now have an opportunity cost if I bet somewhere else,” McClintic told me. “The underlying goal is to provide as many different ways as possible to get into customers’ minds.”

Fanatics today has only a sliver of a fraction of the market share of its sports betting competitors, but “it’s way too early in the game to anoint winners and losers in perpetuity,” Daniel Wallach, a prominent sports betting and gaming attorney, told me. The three most populous states—California, Texas, and Florida—don’t yet allow sports betting. As they open up, he said, “every player has to line up at the same starting line.”

A more immediate concern for Fanatics has been a brewing battle over alleged antitrust violations, spearheaded by the legendary attorney David Boies on behalf of trading card company Panini America, which has one of the largest shares of the U.S. trading card market. Panini alleges that in purchasing Topps—and scooping up licensing agreements with leagues and various athlete unions—Fanatics had, in effect, cornered the market in the United States. “These aren’t just deals,” Boies has said. “These are 20-year licensing deals. Decades-long deals. When you do deals of this length, that have never been done before in the modern era of trading cards, you are effectively leaving no one to compete with you. That’s the definition of monopoly.” In addition, Panini’s lawsuit points out, in 2022 Fanatics acquired a majority stake in the same American printer that Panini relies on for production.

Fanatics has countersued, on the basis of “tortious interference with business relations.” Rubin told me the arrangement with the players’ unions had been arrived at “fair and square. We went out with a broader vision that was better for fans, better for players, better for sports properties, and everyone decided it was the best way to go,” he said. “I can understand that [Panini] is disappointed, but I think they sued us for [them] sucking. That’s the truth.”

Still, there are signs that sports fans have started to chafe at Fanatics’ extraordinarily dominant presence in their lives. In September, The Philadelphia Inquirer published a piece on a run of Fanatics-made Eagles shirts featuring misplaced graphics, some of them crooked, as if a belligerent toddler had dropped them onto the fabric at random. When Eagles fans posted images of the shirts on social media, their replies were filled with complaints about other Fanatics-made items. The revolt echoed what happened in March when the NHL announced that Fanatics was replacing Adidas as the league’s official on-ice uniform provider. Hockey watchers flooded social media to note the company’s ongoing issues with sizing and graphics. Rubin “turned Fanatics into a behemoth not by selling quality products at a fair price,” the sports writer Drew Magary argued recently on Defector. “Instead, he made it easy for leagues to turn around swag quickly (although not always) and cheaply.”

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned in business—own your mistakes,” Rubin wrote on social media after the Eagles fiasco. “Any time we let any fan down, it’s a failure on our part, and that’s on me.”

It doesn’t take a particularly vivid imagination to see how Fanatics might expand, octopuslike, until it has its arms on every part of the sports business. It could create podcasts and YouTube livestreams, like DraftKings, or acquire a television network, like Bally. It could make investments in ticketing, allowing a fan in Boston to buy Red Sox seats—and a Rafael Devers jersey—and accumulate enough points to add in a free bet on the home team. But Rubin, despite my best efforts, demurred whenever I asked him about further expansion: “My focus is on the core pillars of the business,” he said, though those core pillars seem to be multiplying at a terrific pace. He was similarly circumspect when discussing the prospect of a Fanatics IPO. “I think we’ll go public when we’re ready,” he said.

If there is a next step he is willing to talk about, it’s his ongoing efforts to transform Fanatics, a company born as a behind-the-scenes conveyor of goods, into a recognizable brand. “You want to be the brand that people trust, that people think, ‘Okay, whenever I want to do anything digital related to sports, this is where I’m going,’” Rubin told me. “We’re young. You gotta remember: Five years ago, people were just starting to learn about us.” In that sense, Rubin’s growing fame could be one of the most powerful tools he has.

In total, Rubin spent about an hour on the floor of the Dallas Card Show. At around 3 p.m., with the camera crew still trailing resolutely behind, he and his entourage made their way through the lobby and down a long hallway, toward a back room. The place was piled high with Texas A&M jerseys. Almost all of them had been signed. The signer in question, former quarterback Johnny Manziel, jumped to his feet on Rubin’s arrival, and the two embraced. Manziel invited Rubin to visit him the next time he was in Scottsdale, Arizona. “We’ve got a good crew out there. We’ll get into some trouble.”

“No doubt,” Rubin said.

In the next room, the legendary Oakland Athletics outfielder Jose Canseco was mid-signature, a half-eaten hot dog balanced on his lap. Canseco and Rubin aren’t friends, but Rubin is close with the slugger’s daughter, Josie, a runway model and Instagram influencer. “She has a lot of nice things to say about you,” Canseco said, disappearing Rubin inside his biceps, which have the circumference of ripe watermelons.

They bantered for a bit, then Rubin checked the time. In a few hours, he would need to fly back to Philadelphia, and on to Washington, to attend the start of the Commanders’ season as a guest of the team’s new owner, Josh Harris. Meantime, Rubin was getting hungry. What did people eat in Dallas? Barbecue, a staffer suggested. “Pick out a restaurant, and let’s get the whole team in there for a meal,” Rubin said.

Break time. In a conference room off the main hall, Rubin reclined in his chair and sipped contemplatively from a bottle of sparkling water. He answered a few questions distractedly and then thumped the butt of the water bottle onto the table. “Sorry,” he said. He was having trouble thinking about anything but a retailer he’d met earlier in the day who sold cards in China. “The guy says he’s clearing $30 million a month,” Rubin exclaimed. “In a market I hadn’t ever really fully considered. That tells you what’s possible with the growth of this business, right? And we’re like 5% into doing what we want to do. Brother, we’ve just begun.”

Michael Rubin, the billionaire CEO of Fanatics, splits his time between three primary residences—four, if you count the new $70 million pied-à-terre in the Hollywood Hills, overlooking downtown Los Angeles. Tuesdays through Thursdays are reserved for his penthouse in New York’s Greenwich Village, not far from the main Fanatics headquarters. Thursday nights, it’s back to Philadelphia, where he grew up, and where his eldest daughter is finishing high school—unless it’s summer, in which case Rubin decamps to his 8,000-square-foot modernist mansion in Bridgehampton, on the South Fork of Long Island, New York.

Commuting is no fun for anyone. For an executive with a work and social calendar resembling a Pollock painting, traffic and other forms of quotidian delay are an even bigger menace, and Rubin eschews earthbound travel unless absolutely necessary, preferring to fly everywhere he goes, whether by private jet or on Fanatics’ “two helis,” as he calls them. “I’m in the air so much,” he told me this fall. “Every which way, I’d die without it.”

On the second Saturday in September, Rubin took his jet from Philadelphia to a private air hangar near the Dallas Fort Worth airport and then climbed into a rented Tahoe, which carried him to the local Fanatics office. He then reboarded the SUV and drove a few more miles north, to the site of the Dallas Card Show. Founded a decade ago, as a modest, 10-table swap meet, the card show is today one of the most important events for the multibillion-dollar sports collectibles industry—a sector that Fanatics, valued at $31 billion and already the single biggest manufacturer and distributor of sports fan apparel in the U.S., is intent on dominating.

Rubin waded into the scrum of the conference hall tentatively, his hands jammed into the pockets of his black jeans. Although he’s been celestially wealthy since 2011, when he sold his first company, GSI Commerce, to eBay, for $2.4 billion, Rubin has an unassuming presence for a business mogul—he’s slender, 5-foot-9 in sneakers, with brown hair that he wears in a kind of modified crew cut. His most defining characteristic is his eyes, which are close-set and densely lashed. Murmurs and nods followed him across the floor, as did a camera crew assigned to capture footage for Fanatics. “I don’t think of myself as a celebrity,” he said. “But I do get a fair amount of attention from young guys, let’s call it 20 to 30 years old, because they think, ‘Okay, yeah, I want to be like that guy in business.’”

A few yards in, the first selfie-seeker materialized. He was wearing a Cincinnati Reds jersey and an oversize plastic baseball helmet. “Love what you do,” Baseball Helmet Man said. “Thanks, brother,” Rubin replied, smiling up into the iPhone lens. More murmurs, more nods. One selfie begets another, and another, ad infinitum. Rubin posed dutifully for them all. Would he autograph a hundred-dollar bill? He would, gladly. Would he talk about the Braves’ World Series chances? He would, at exhaustive length. Would he accept a résumé from a college graduate seeking work at Fanatics? He would, with a caveat: “I’ll pass this along to the right people and see what they can do,” he said. “I’ll try, brother.”

Rubin, despite his protestations to the contrary, has achieved an extraordinary degree of mainstream stardom in recent months—partly owing to the vertiginous growth of Fanatics (an estimated $8 billion in revenue in 2023 alone) and largely due to his friendships with nearly every big name in the worlds of hip-hop and professional sports. James Harden and Joel Embiid, the NBA legends, are good pals, as is the rapper Meek Mill, whom Rubin successfully lobbied to have released from jail in 2018 and later pardoned on the original bogus gun charges. When Rubin threw a Fourth of July “white party” at his estate on the Hamptons, earlier this year, Meek and Harden showed up, as did Justin Bieber, Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Tom Brady, and Leonardo DiCaprio. All were clad in white. Usher played a set, and Kim Kardashian knocked back 11 shots. TMZ called the bash a “who’s who of fame.”

But the attendees of the Dallas Card Show were far more interested in different developments. Fanatics, known for making and selling licensed apparel for professional and college sports teams, had acquired Topps, the trading card company, in 2022. It had also recently moved into online sports betting, launched a live shopping app, and acquired PWCC Marketplace, a popular auction and sales site for trading cards and sports memorabilia. Depending on your point of view, these business moves either made Rubin a heedless monopolist whose core products were beginning to suffer for sake of growth or the benevolent king of the most powerful empire in sports fandom.

The previous night, in the kind of flex he specializes in, Rubin had invited his friends Odell Beckham Jr. and Derek Jeter to a studio at Fanatics HQ in New York to open boxes of Topps cards—a “break,” as industry insiders call it. Halfway through the livestream, he’d FaceTimed a different buddy, Tom Brady, who showed off a pile of jerseys from various points in his career. “It’s really all one customer base,” Rubin told me in Texas. “Look around the room. We know everyone here is into trading cards, but how many also buy licensed apparel? And how many bet on sports?” He caught himself. “Well, it’s not legal in Texas yet, so how many bet on sports illegally? Probably a lot. Again: It’s one customer base, and we can reach them all.”

Yet Rubin allowed that he was “smart enough to know the shit I don’t know,” and a major part of the Topps acquisition—and deals with various leagues and players’ unions for the likenesses of athletes from the NFL, MLB, and NBA—had involved schooling himself in the intricacies of the collectible-card market. “It’s why I come to events like this,” he said. “It’s important for me to hear what we’re getting right, but I like getting beat up by people too. When they tell me things we’ve managed to fuck up or get wrong, it doesn’t bother me. You have to always be learning, or you’re dead.”

He stopped at a booth rented by Roadshow Cards, a collectibles business with stores in Texas, New York, Kentucky, and California. “Be honest with me,” Rubin said to Cody Crim, a proprietor. “What could we be doing better?” Crim exchanged a glance with his colleagues. How transparent, exactly, was he supposed to be? “You guys are already a breath of fresh air,” he began, tentatively. “Like, the last CEO”—of the preacquisition Topps—“I never saw him in an office setting, let alone at a place like this. It’s good just to talk to you. It’s helpful.”

“I told you, you could be honest, brother,” Rubin said.

After what appeared to be an agonizing—and rapid—series of mental calculations, Crim relented. Sometimes, he allowed, major Topps products weren’t hitting his stores on the day of release. This was a problem, since a savvy collector might attempt to find the cards elsewhere. “Okay,” Rubin nodded. “Product on release day. Got it. We’re on it. What else?”

I was book stupid. I really was,” Rubin told me one afternoon this fall, at his brick-lined office on the eighth floor of Fanatics’ headquarters on New York’s Morton Street. “I got an 800 on my SATs—800 combined, not just on one half. I hated school. But I believed I could outhustle anyone.”

“Michael’s not as educated as some,” suggested a communications staffer, who was seated to his boss’s left, with his back to the Hudson River. “But he’s intellectually curious.”

“He’s calling me a fucking idiot,” Rubin said.

“No. Intellectually curious,” the staffer said. “He asks questions.”

Rubin could agree with this. “Always,” he said.

The tale of Rubin’s ascent has been frequently told: the ski-tuning shop he started out of his parents’ basement as a teen in the suburbs of Philly, which evolved into selling overstock ski equipment at malls, and then overstock sports apparel in general; his early departure from Villanova with a GPA south of 2.0. Rubin then founded Global Sports Incorporated, which included a women’s footwear brand. When he was 23, he moved into e-commerce management and launched GSI Commerce.

GSI was a product of the early internet era, when corporations such as Toys “R” Us, Estée Lauder, and Bed Bath & Beyond sold nearly all their products through brick-and-mortar storefronts. Rubin’s pitch was straightforward: He and his team would build and manage the brands’ e-commerce sites while also handling shipping and fulfillment, allowing them to reach a vast new online audience. Soon, hundreds of millions of dollars in transactions were being shunted through GSI-run sites.

As the company grew, so did Rubin’s forays into licensed sporting goods: In 2002, he won the right to sell Nascar-branded gear online, and in 2005, he reached a similar deal with the NHL. The NBA and NFL followed. Rubin told me that by 2011, the year GSI was acquired by eBay, the sports vertical of the company alone was seeing revenue north of $250 million annually. Not enough. What about college sports? “We had a strong foothold with professional sports, but not with, like, the NCAA. But there was this company in Florida that had been successful there, and so I flew down to see them.” The company, a regional retail chain that sold sports fan gear and had just moved into e-commerce, was called Fanatics. Rubin bought it more or less on the spot, for $277 million.

The brand was initially folded into the deal with eBay, but the auction site had little use for it: eBay brass didn’t like the idea of competing with its own merchants. Shortly after the acquisition closed, Rubin arranged to buy Fanatics back, at a nearly $90 million markup.

Again, as he had in the early days of GSI, Rubin saw opportunity with Fanatics. “My original thought was like, ‘Look, there’s this little company in Seattle called Amazon and they kind of kill everybody. And there’s this other company in China called Alibaba. They’re killing everybody else.’” Rubin was sure that Fanatics could attain something close to that level of success by focusing on selling to sports fans alone—surveys regularly show approximately 70% of Americans count themselves as committed fans—but not in its current form. “We didn’t have a great point of differentiation,” Rubin said. “And I had the view that we’d be dead if we didn’t completely transform the business. By the way, I was right.”

That reinvention ultimately hinged on how licensed fan gear was made and sold. For years, sports leagues outsourced manufacturing to various brands and their network of factories around the globe, and GSI sold it online. But there were some drawbacks to the setup, the most obvious being the speed at which apparel reached fans. Factories could take as long as nine months to make a line of jerseys, at which point a player might have retired or been sent back to the minors. Leagues frequently found themselves awash in jerseys that no one wanted (or empty-handed in the event an underdog team or player had a breakout season).

“Let’s just make them ourselves,” Rubin remembers thinking. Manufacturing wasn’t quantum physics; it did require capital, but SoftBank and Silver Lake, among other investors, were happy to provide it. Beginning in 2012, Rubin requested meetings with the heads of the NFL and NBA, and pitched them on his vision: Forget the network of factories. I’ll make the apparel for you, and I’ll make it quickly, in the space of weeks, with endless amounts of customization. If Brady had another record-setting season, Fanatics could have nine variants of his jersey on sale by Super Bowl Sunday. If one day, Taylor Swift fans happened to drive up sales of a certain Kansas City Chiefs jersey by 400%, Fanatics would be ready.

“I basically spent two years explaining to commissioners how they could build their own, better direct-to-consumer business,” Rubin said. “I said, ‘Your retail business will get bigger, you’ll get a bigger percentage of the sales, and we’ll provide you with all this customer data that you can use.’” No one ever said no, Rubin recalled: “They just said yes slowly.”

Passion Points

How Fanatics is expanding its empire to touch all parts of sports fans’ lives

Magic Johnson, a longtime friend of Rubin’s and a former member of the Fanatics board (Johnson left upon taking an ownership stake in the Washington Commanders, citing a conflict of interest), said that his friend can be exceptionally persistent. “He’s relentless,” Johnson said. “It’s constantly, ‘What’s next, what’s next, what’s next?’” Johnson added: “You absolutely never want to underestimate Michael.”

In 2018, the NFL, Nike, and Fanatics announced a three-way, 10-year deal for Fanatics to design and manufacture all official Nike fan apparel for the league; Fanatics reached a similar arrangement with the MLB the same year. (Both lines launched in 2020, meaning that if you’ve purchased a piece of Nike-branded NFL or MLB clothing in the past three years, you were actually purchasing a Fanatics-made product.) Rubin has since acquired the rights to make gear for hundreds of colleges and universities and the best baseball team in Japan, the Tokyo Giants. In March, Fanatics secured a licensing deal for the NHL’s on-ice uniforms, starting with the 2024–2025 season, and through the 2016 purchase of the U.K. sports-merchandise company Kitbag, the e-commerce rights to Manchester United and other major European soccer clubs.

The Kitbag acquisition is a good example of the Fanatics ethos under Rubin: Where you can’t elbow a competitor out of the way, you might as well swallow them whole. The company pulled a similar trick last year with the sports-apparel brand Mitchell & Ness, which Fanatics purchased for a reported $250 million in conjunction with a group of investors that included Maverick Carter, Meek Mill, and Jay-Z. Add the company’s 2017 acquisition of VF Licensed Sports Group, including apparel brand and MLB uniform maker Majestic, and its 2018 minority stake in Lids, the ball-cap retailer, and there are vanishingly few ways to buy sports apparel in 2023 that do not involve Fanatics.

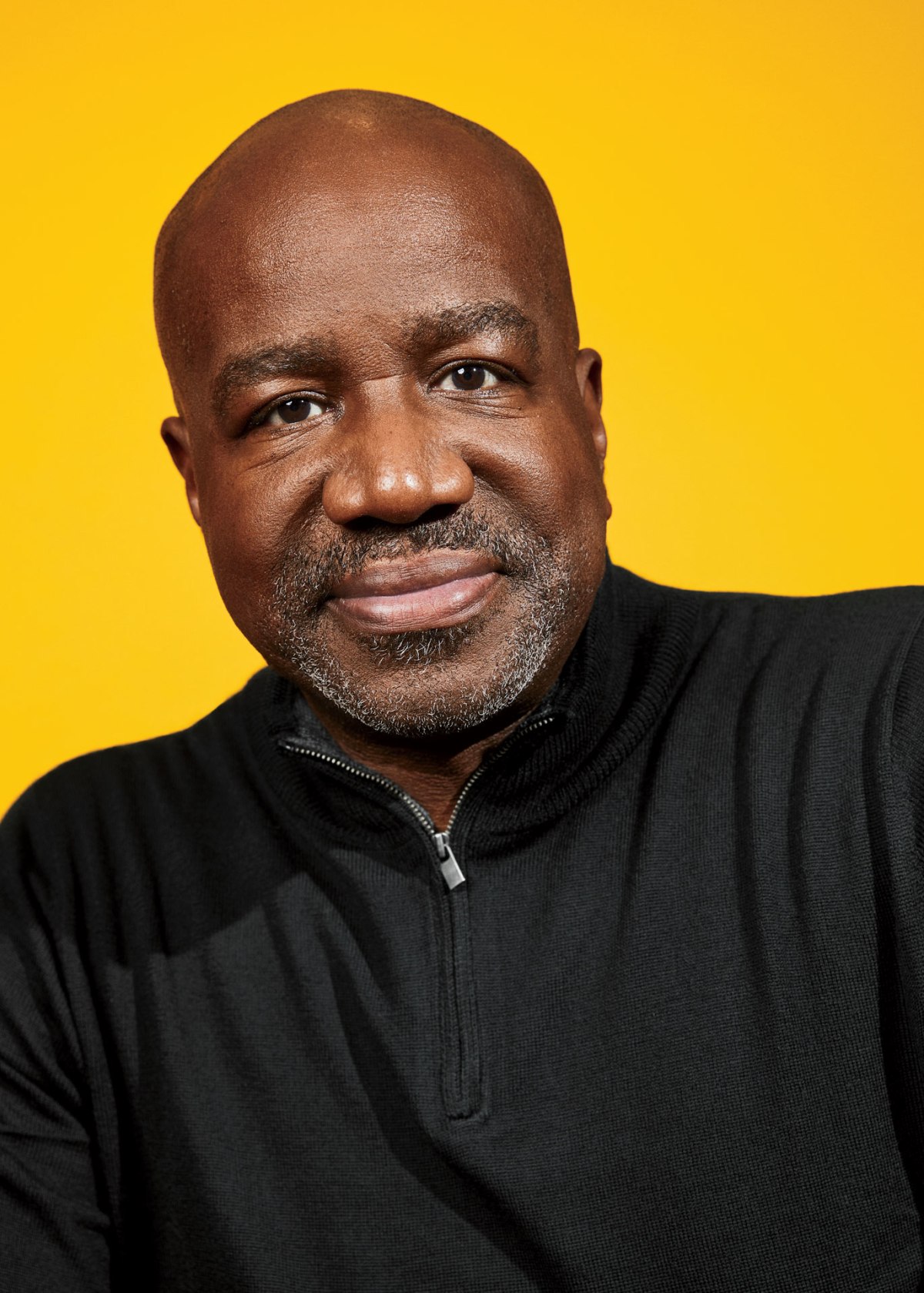

Or, for that matter, to be a sports fan or viewer, full stop: When I spoke to Orlando Ashford, the chief people officer of Fanatics, he mentioned that the company had arranged to handle fulfillment of all sports-related wishes for the Make-A-Wish Foundation, the 43-year-old nonprofit. Fanatics is donating $10 million for the privilege and is not making any money from the arrangement. Yet it’s hardly a stealth venture. In the media, the initiative is now referred to by its full name: Fanatics Make-A-Wish.

Rubin likes to describe the growth of Fanatics as a two-stage proposition: “First decade,” he told me, “we got everything set up. Now, in the second decade, we’re really ready to grow.” He predicted that in coming years, Fanatics would expand to “many times” its current size.

Those closest to Rubin see little reason to doubt him. “I think Fanatics will be the Amazon of the sports world, I really do,” says Rich Kleiman, the longtime manager of NBA superstar Kevin Durant and the CEO of the sports and entertainment company Boardroom. Just as Jeff Bezos merely started with a bookstore, “that’s what I see Michael doing for sports,” says Kleiman, “which you’ve gotta remember is the most influential and popular force in society right now.”

Of course, the bigger a company grows, the more unwieldy it becomes. And while Rubin once had his hands on nearly every decision Fanatics made, that’s no longer possible, given its gargantuan footprint—18,000 employees in dozens of states and across 15 countries, not counting 5,000 Lids staff. Rubin has adjusted by hiring senior execs from FanDuel, Snap, Dick Clark Productions, and elsewhere to run the ever-multiplying number of Fanatics verticals. “My thing is to be involved where I can add value, and not to get involved at all where I won’t,” Rubin told me.

In December 2022, Fanatics closed on a $700 million investment round led by Clearlake Capital, driving its valuation up fivefold from $6.2 billion three years prior. The money could help cover the cost of all the sundry investments—some of which have proved shorter-lived than others. In May, for example, Rubin announced to staff that Fanatics was selling its 60% stake in the NFT firm Candy Digital, citing the “imploding NFT market.”

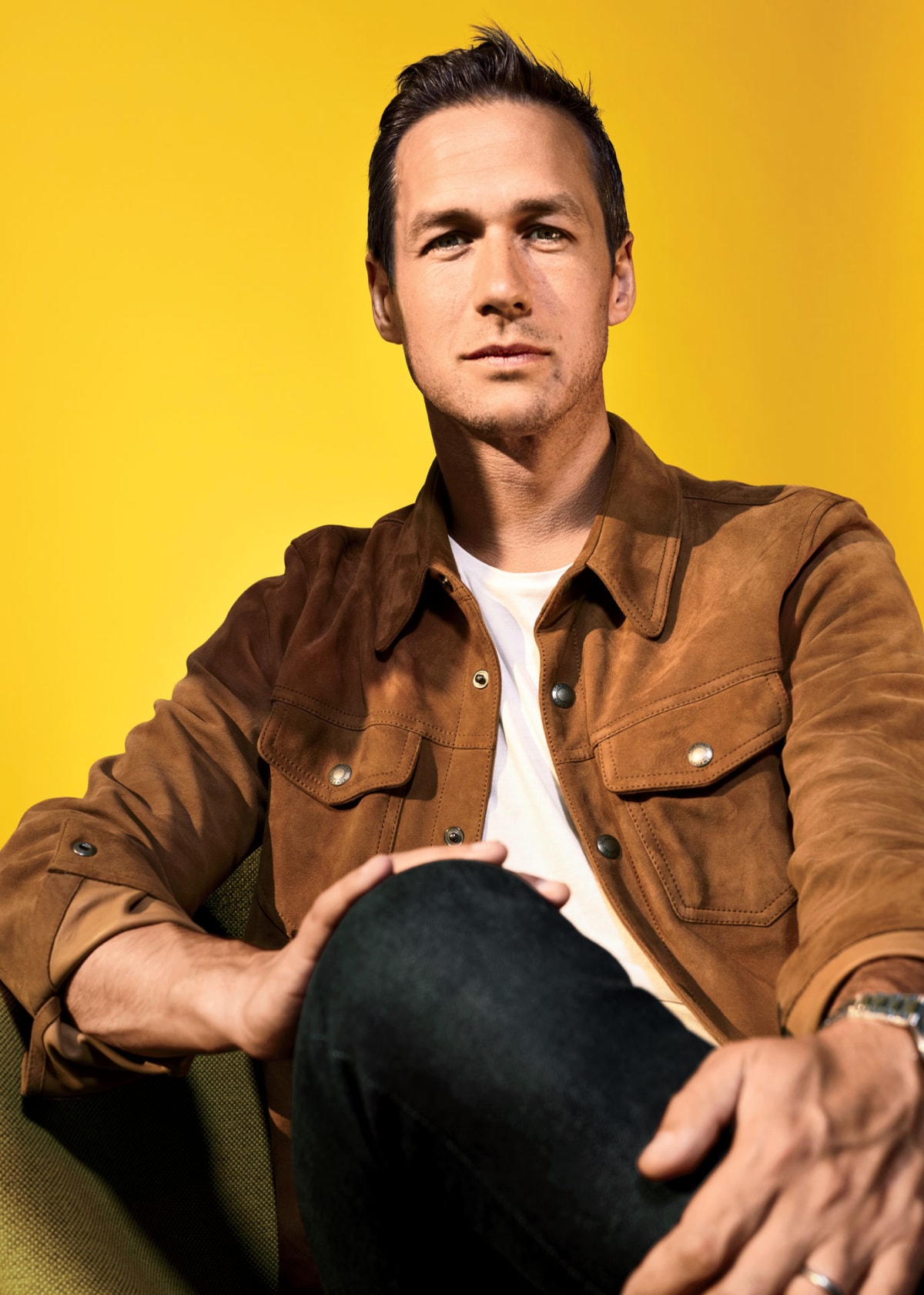

Fanatics is pushing into other challenging spaces. Sports betting, for example, is dominated by deeply entrenched players. Matt King, the former CEO of FanDuel and now Fanatics’ betting and gaming chief, told me the strategy of early entrants had been to “spend massive amounts on advertising to acquire customers they hoped to monetize later.” Fanatics would not be able to match that advertising blitz, he went on, but nor would it want to: “We think we can adopt a strategy that really leads with product, leads with loyalty and rewards, and lets virality and word of mouth play their roles.” Make the experience of sports betting more intuitive, and disgruntled FanDuel users will come to you.

This fall, Scot McClintic, chief product officer of Fanatics Betting and Gaming, gave me a virtual tour of the Fanatics Sportsbook app, which is currently available for use in five states: Massachusetts, Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee. (In August, Fanatics gobbled up the American arm of the Australian gambling operation PointsBet for $225 million, which has now added eight more states.) There is no browser-based Fanatics Sportsbook, he explained; all the design team’s energy had gone into crafting a better mobile-based experience. But the most striking difference could be the Fanatics Sportsbook’s integration into the larger company ecosystem: On the app, customers can gamble with cash or FanCash, reward points that are generated by wagering or buying apparel and other merchandise on the Fanatics site. The more you wager or buy from Fanatics, the more free bets you’re able to place. “I now have an opportunity cost if I bet somewhere else,” McClintic told me. “The underlying goal is to provide as many different ways as possible to get into customers’ minds.”

Fanatics today has only a sliver of a fraction of the market share of its sports betting competitors, but “it’s way too early in the game to anoint winners and losers in perpetuity,” Daniel Wallach, a prominent sports betting and gaming attorney, told me. The three most populous states—California, Texas, and Florida—don’t yet allow sports betting. As they open up, he said, “every player has to line up at the same starting line.”

A more immediate concern for Fanatics has been a brewing battle over alleged antitrust violations, spearheaded by the legendary attorney David Boies on behalf of trading card company Panini America, which has one of the largest shares of the U.S. trading card market. Panini alleges that in purchasing Topps—and scooping up licensing agreements with leagues and various athlete unions—Fanatics had, in effect, cornered the market in the United States. “These aren’t just deals,” Boies has said. “These are 20-year licensing deals. Decades-long deals. When you do deals of this length, that have never been done before in the modern era of trading cards, you are effectively leaving no one to compete with you. That’s the definition of monopoly.” In addition, Panini’s lawsuit points out, in 2022 Fanatics acquired a majority stake in the same American printer that Panini relies on for production.

Fanatics has countersued, on the basis of “tortious interference with business relations.” Rubin told me the arrangement with the players’ unions had been arrived at “fair and square. We went out with a broader vision that was better for fans, better for players, better for sports properties, and everyone decided it was the best way to go,” he said. “I can understand that [Panini] is disappointed, but I think they sued us for [them] sucking. That’s the truth.”

Still, there are signs that sports fans have started to chafe at Fanatics’ extraordinarily dominant presence in their lives. In September, The Philadelphia Inquirer published a piece on a run of Fanatics-made Eagles shirts featuring misplaced graphics, some of them crooked, as if a belligerent toddler had dropped them onto the fabric at random. When Eagles fans posted images of the shirts on social media, their replies were filled with complaints about other Fanatics-made items. The revolt echoed what happened in March when the NHL announced that Fanatics was replacing Adidas as the league’s official on-ice uniform provider. Hockey watchers flooded social media to note the company’s ongoing issues with sizing and graphics. Rubin “turned Fanatics into a behemoth not by selling quality products at a fair price,” the sports writer Drew Magary argued recently on Defector. “Instead, he made it easy for leagues to turn around swag quickly (although not always) and cheaply.”

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned in business—own your mistakes,” Rubin wrote on social media after the Eagles fiasco. “Any time we let any fan down, it’s a failure on our part, and that’s on me.”

It doesn’t take a particularly vivid imagination to see how Fanatics might expand, octopuslike, until it has its arms on every part of the sports business. It could create podcasts and YouTube livestreams, like DraftKings, or acquire a television network, like Bally. It could make investments in ticketing, allowing a fan in Boston to buy Red Sox seats—and a Rafael Devers jersey—and accumulate enough points to add in a free bet on the home team. But Rubin, despite my best efforts, demurred whenever I asked him about further expansion: “My focus is on the core pillars of the business,” he said, though those core pillars seem to be multiplying at a terrific pace. He was similarly circumspect when discussing the prospect of a Fanatics IPO. “I think we’ll go public when we’re ready,” he said.

If there is a next step he is willing to talk about, it’s his ongoing efforts to transform Fanatics, a company born as a behind-the-scenes conveyor of goods, into a recognizable brand. “You want to be the brand that people trust, that people think, ‘Okay, whenever I want to do anything digital related to sports, this is where I’m going,’” Rubin told me. “We’re young. You gotta remember: Five years ago, people were just starting to learn about us.” In that sense, Rubin’s growing fame could be one of the most powerful tools he has.

In total, Rubin spent about an hour on the floor of the Dallas Card Show. At around 3 p.m., with the camera crew still trailing resolutely behind, he and his entourage made their way through the lobby and down a long hallway, toward a back room. The place was piled high with Texas A&M jerseys. Almost all of them had been signed. The signer in question, former quarterback Johnny Manziel, jumped to his feet on Rubin’s arrival, and the two embraced. Manziel invited Rubin to visit him the next time he was in Scottsdale, Arizona. “We’ve got a good crew out there. We’ll get into some trouble.”

“No doubt,” Rubin said.

In the next room, the legendary Oakland Athletics outfielder Jose Canseco was mid-signature, a half-eaten hot dog balanced on his lap. Canseco and Rubin aren’t friends, but Rubin is close with the slugger’s daughter, Josie, a runway model and Instagram influencer. “She has a lot of nice things to say about you,” Canseco said, disappearing Rubin inside his biceps, which have the circumference of ripe watermelons.

They bantered for a bit, then Rubin checked the time. In a few hours, he would need to fly back to Philadelphia, and on to Washington, to attend the start of the Commanders’ season as a guest of the team’s new owner, Josh Harris. Meantime, Rubin was getting hungry. What did people eat in Dallas? Barbecue, a staffer suggested. “Pick out a restaurant, and let’s get the whole team in there for a meal,” Rubin said.

Break time. In a conference room off the main hall, Rubin reclined in his chair and sipped contemplatively from a bottle of sparkling water. He answered a few questions distractedly and then thumped the butt of the water bottle onto the table. “Sorry,” he said. He was having trouble thinking about anything but a retailer he’d met earlier in the day who sold cards in China. “The guy says he’s clearing $30 million a month,” Rubin exclaimed. “In a market I hadn’t ever really fully considered. That tells you what’s possible with the growth of this business, right? And we’re like 5% into doing what we want to do. Brother, we’ve just begun.”