Interview: Jamil Jan Kochai, author, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak

For Jamil Jan Kochai, 30, fiction is a “comforting space” in which he explores his family’s collective memory. His debut novel, 99 Nights in Logar (2019), drew on his childhood memories of visiting Logar in eastern Afghanistan. His latest, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories (Penguin Random House), is a collection of 12 short stories. Excerpts from an interview:

The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories is about the inheritance of loss and the intergenerational sorrow running through Afghan-American families. Did you have a particular theme in mind for the collection?

These stories were written at different points of time. Unlike a novel, an anthology is not a unified project. When I looked at these stories while putting them together for the collection, I kept thinking about the unifying theme. The theme that kept coming up was this notion of haunting; often, it was not a conscious exercise. But there is a missing character at the heart of every single story. Besides, there is one character that haunts the rest of the stories, whether it’s Watak (my father’s brother who was lost in the war) or other characters that play the same role, like the character of the son in the story Return to Sender. The characters in these stories are also haunted by history and the spectre of war. My agent, editor and I came to the conclusion that it made sense to call the collection The Haunting of Hajji Hotak because all these stories were haunted in one way or another.

In what ways did these stories emerge from your own lived experiences?

Many of these stories are autobiographical. I became a fiction writer because it’s a comforting space where I can create distance between myself and my characters. They are oftentimes, in different ways, representations of my family members. I draw a lot from my family history. Fiction allows me to re-explore this family, which is based on my own family, in a completely new and radical way — whether it’s through video games in the opening story (Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain) or through resumes (Occupational Hazards) or through a surveillance agent in the title story The Haunting of Hajii Hotak. I am then able to understand the family in new ways.

And this is something that being a memoirist or an essayist would not allow you to do?

I really admire memoirs and essays. For me, being able to approach a story that’s very dear to me or real-life events or actual memory through the filter of fiction allows me to create distance between myself and my characters; it’s a fictional barrier. I find that very comforting. I really need that barrier when I am approaching a story based on real-life events. Secondly, I always feel this sense of liberation and freedom in writing these stories: I can go wherever I want. I can start a story with a memory or a real-life event, with an actual person I know, but then I am still able to, at any point, go in whatever direction I want, whether it’s fantastical, magical realist or surreal situation. Fiction allows me to break off from the memory. And as a writer, I need that freedom to tear myself away from the memory at any point. I think I would feel very restricted and very vulnerable otherwise.

The collection stands out for the ingenuity of prose and the stylistic experimentation. There is a little bit of magic realism too.

When I first started reading fiction seriously, I enjoyed the story, characters, plot development and thematic elements. But, after that, it was actually reading the sentences themselves. I am a big lover of sentences: really beautifully constructed, long, sometimes-running-into-three-page sentences. That’s my dream. It gets me. That is why I read fiction. Writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Toni Morrison or Barry Hannah or José Saramago that I read pushed the boundaries of what prose could do. That was incredibly inspirational for me. When I am entering a story, I am always looking for ways through which I can push the form of the story itself. I am looking for ways through which I can play around with my sentence structures. I am coming at it from a very playful sense. I just want to see what I can get away with in a story. Sometimes it can lead to very experimental form. There is a story that is written in the form of a resume and another in just one sentence. The story written in one long sentence is the one I am really proud of; it was not something that I did consciously, it’s something that naturally came about as a reflection of the character herself. So, whenever I am making a stylistic or formal decision alternately, if it’s not benefitting or telling me more about the character, then it’s something that I am not going to do. I don’t want to do these things just as a gimmick.

What kind of family stories have you lived with that have found their way to this collection?

The sense of melancholy and sorrow is something that I grew up with from a very young age. For example, the story of Watak. His tale was with us since I was a child; his photograph would be hanging in our prayer room. Every time I prayed, I would look up and see Watak watching over us. He was a figure that I had never known. But, in a sense, his loss had always been with us. He had been someone whose loss had deeply affected my father. There was this profound sadness in the family that you could feel in our household as a whole. It was not just the loss of Watak or Gulaba, my father’s sister, or other family members that we lost, but it was the sense of having lost the entire world. I now live in West Sacramento, California, but everything that I know about storytelling, everything that I know about stories in general, goes back to the land that we lost: Logar in Afghanistan. As I am beginning to conceptualise what a story is, it’s always rooted in this sense of loss and melancholic nostalgia. You can feel this in my stories. When I began writing this collection, I wanted to explore the hauntings — of land or person or loved ones — but also, in some weird way, to bring back the ghosts through these stories.

What was your response to a recent review in The New York Times that was unfairly harsh to your book?

It was incredibly disappointing to read the review. The NYT is a prominent publication. And it’s a review that I have been waiting for. For me, it was an honour to have been considered for the NYT book review. When I read it, I found that it was more than just a negative review. There is a paragraph in which the reviewer says something about the formal experimentation at the cost of the substance of the story. I am completely fine about it. That’s actually a concern that I myself had about the stories. So, while it was not great to read it, it’s still a compelling literary argument. It was when I got to this section about fixating on whiteness that I became not just disturbed, but a little bit angry that my book had not been given a very careful reading. It was a very strange comment because there are not too many White characters in my stories; in the 267-page book, maybe 10 or 15 pages figure White characters. To focus on that particular element in the review felt like a misreading, and even dishonest, to me. The reviewer made a comment that when I wanted to signal that a character was bad, I painted it as White. Since I have very few White characters in my stories, it was confusing. And then there was a comment that I paint all the American characters broadly as imperialists. It was again not true because almost all of my American characters are Afghan-Americans. I didn’t understand how I painted them as imperialists.

Finally, in the last paragraph, which was complimentary, he writes that The Haunting of Hajji Hotak is the strongest story in the collection, but he misread the narrator. He thought that the narrator was the son of Hajji Hotak. I think it’s very clear that it was a surveillance agent that didn’t belong to the family. The part that angered me the most was that my book had been entirely misread. There are inaccuracies in the text. It seemed very clear to me that it was not a careful, honest review. It was a repetition of a narrative that I have seen my entire life, which is: to use Afghanistan to refocus on White characters, to refocus on the White soldiers, to refocus and recentre Whiteness itself. It was deeply disappointing.

You were born in Pakistan. Tell us about your visits to Logar and its centrality in your fiction.

As a child, Afghanistan was a dreamscape for me. Everything I have known about storytelling originated in Logar. Every story that my parents, my grandparents or my aunt told me were about Logar. When I was a child and I returned to Logar for the first time at the age of six, there was something about the location that seemed unreal to me from the very beginning. But then, actually going to Logar, living there and meeting the people was a completely different experience. It altered my conception of Logar. I completely fell in love with it. I was immediately enraptured by the new location, with the orchards and the streets and the mountains always looming in the distance. All my cousins lived over there. All the new friends I had to make spoke the same language as me and seemed to understand my own position.

When we left, it was difficult for me even as a small child. I would think about Logar all the time. And when we came back again after I had turned 12, there was a similar sense of longing and loss. I felt an intense bond with the location as well. Since then, I have been going back every few years or so. So, while it began as a land or as a story or a dreamscape, it became real to me very quickly. I was visiting quite often; I was doing historical research on Logar. I was looking through the landscape. I would talk to my father about how everything had come together initially in terms of geography. So, in that sense, it was also important for me to represent the very real issues, the actual material reality of what was going on in Logar during the Soviet invasion and the American occupation. For me, the balancing of the fantastical and of the very real is important. I want to make sure that both of those elements are balanced in one way or another in my stories. Logar is very dear to me; I spent a lot of time there, both physically and also a lot in my head. And I will continue to write about it.

What was your response to the fall of Kabul to Talibans?

It was an intensely nerve-wracking time. I got a lot of calls and messages from my family back home in Logar and Kabul. They were very worried. There was a lingering fear when the Mujahideen took Kabul after the fall of the Communist-backed government. After that, intense carnage and massive civil war unfolded. Horrible atrocities were committed on all sides. For many of my family members, there was a desperate need to get out of the country. Even today, things are not going well. It’s a very dire situation, whether it’s about Taliban policies with the girls’ schools or the continuing of the sanctions by the US which have completely levelled the economy. Last month, my wife visited Kabul, where she has spent most of her life. She said to me that the poverty she saw there now was more acute than it has ever been. People are starving on the streets. Just a couple of months ago, they had jobs. But now they are forced to live on the streets, uncertain of where their next meal will come from. It’s an incredibly desperate situation. It’s being made worse by the policies of the current regime in Afghanistan, and also by the Biden-led US administration. It’s difficult to watch what is going on there. We keep hoping that at some point the Biden administration is going to lift the sanctions, that he is going to have some sense of mercy upon these poor people, but it’s more likely that it’s not going to happen. The Afghan-American community in the States have been making different efforts, figuring out how to get Afghans out of the country, and also how to get money and resources into the country through fund raisers and food drives, etc. But these efforts seem like the bandage on the bullet wound.

Could you name some young writers from Afghanistan writing fiction?

There is not too much fiction writing from Afghanistan. Many books that are being published and given publicity are written by White Americans and White Europeans. It’s very rare that an Afghan living inside Afghanistan writes about his/her home. It is also very rare to see fiction by Afghani diaspora community in Europe and the US. I hope that as the Afghani diaspora begins to get more and more embedded with the literary industry here, it will give opportunities to Afghan writers throughout the world, especially Afghan writers back home. There is an Afghan writer called Aria Aber, who has come out with a beautiful poetry collection, Hard Damage. It is a breathtaking book, with words and images that I found devastating. She is currently working on a novel. There is another Afghan-American writer called Sahar Muradi, who is also a very talented poet. I do hope that in the coming years, as I continue to develop my own career as a writer, fiction writers back home are going to be given more chances to publish their work. There must be so much talent there, but for the lack of opportunity or spotlight or because of the war itself, they have not been able to come to the fore. I always wonder how many literary geniuses would have been lost because of the circumstances of war or because they had to spend their entire lives working physical labour in order to keep their families alive. I hope it changes in the future and there is more fiction writing from Afghanistan.

Nawaid Anjum is an independent journalist. He lives in New Delhi.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

For Jamil Jan Kochai, 30, fiction is a “comforting space” in which he explores his family’s collective memory. His debut novel, 99 Nights in Logar (2019), drew on his childhood memories of visiting Logar in eastern Afghanistan. His latest, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories (Penguin Random House), is a collection of 12 short stories. Excerpts from an interview:

The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories is about the inheritance of loss and the intergenerational sorrow running through Afghan-American families. Did you have a particular theme in mind for the collection?

These stories were written at different points of time. Unlike a novel, an anthology is not a unified project. When I looked at these stories while putting them together for the collection, I kept thinking about the unifying theme. The theme that kept coming up was this notion of haunting; often, it was not a conscious exercise. But there is a missing character at the heart of every single story. Besides, there is one character that haunts the rest of the stories, whether it’s Watak (my father’s brother who was lost in the war) or other characters that play the same role, like the character of the son in the story Return to Sender. The characters in these stories are also haunted by history and the spectre of war. My agent, editor and I came to the conclusion that it made sense to call the collection The Haunting of Hajji Hotak because all these stories were haunted in one way or another.

In what ways did these stories emerge from your own lived experiences?

Many of these stories are autobiographical. I became a fiction writer because it’s a comforting space where I can create distance between myself and my characters. They are oftentimes, in different ways, representations of my family members. I draw a lot from my family history. Fiction allows me to re-explore this family, which is based on my own family, in a completely new and radical way — whether it’s through video games in the opening story (Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain) or through resumes (Occupational Hazards) or through a surveillance agent in the title story The Haunting of Hajii Hotak. I am then able to understand the family in new ways.

And this is something that being a memoirist or an essayist would not allow you to do?

I really admire memoirs and essays. For me, being able to approach a story that’s very dear to me or real-life events or actual memory through the filter of fiction allows me to create distance between myself and my characters; it’s a fictional barrier. I find that very comforting. I really need that barrier when I am approaching a story based on real-life events. Secondly, I always feel this sense of liberation and freedom in writing these stories: I can go wherever I want. I can start a story with a memory or a real-life event, with an actual person I know, but then I am still able to, at any point, go in whatever direction I want, whether it’s fantastical, magical realist or surreal situation. Fiction allows me to break off from the memory. And as a writer, I need that freedom to tear myself away from the memory at any point. I think I would feel very restricted and very vulnerable otherwise.

The collection stands out for the ingenuity of prose and the stylistic experimentation. There is a little bit of magic realism too.

When I first started reading fiction seriously, I enjoyed the story, characters, plot development and thematic elements. But, after that, it was actually reading the sentences themselves. I am a big lover of sentences: really beautifully constructed, long, sometimes-running-into-three-page sentences. That’s my dream. It gets me. That is why I read fiction. Writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Toni Morrison or Barry Hannah or José Saramago that I read pushed the boundaries of what prose could do. That was incredibly inspirational for me. When I am entering a story, I am always looking for ways through which I can push the form of the story itself. I am looking for ways through which I can play around with my sentence structures. I am coming at it from a very playful sense. I just want to see what I can get away with in a story. Sometimes it can lead to very experimental form. There is a story that is written in the form of a resume and another in just one sentence. The story written in one long sentence is the one I am really proud of; it was not something that I did consciously, it’s something that naturally came about as a reflection of the character herself. So, whenever I am making a stylistic or formal decision alternately, if it’s not benefitting or telling me more about the character, then it’s something that I am not going to do. I don’t want to do these things just as a gimmick.

What kind of family stories have you lived with that have found their way to this collection?

The sense of melancholy and sorrow is something that I grew up with from a very young age. For example, the story of Watak. His tale was with us since I was a child; his photograph would be hanging in our prayer room. Every time I prayed, I would look up and see Watak watching over us. He was a figure that I had never known. But, in a sense, his loss had always been with us. He had been someone whose loss had deeply affected my father. There was this profound sadness in the family that you could feel in our household as a whole. It was not just the loss of Watak or Gulaba, my father’s sister, or other family members that we lost, but it was the sense of having lost the entire world. I now live in West Sacramento, California, but everything that I know about storytelling, everything that I know about stories in general, goes back to the land that we lost: Logar in Afghanistan. As I am beginning to conceptualise what a story is, it’s always rooted in this sense of loss and melancholic nostalgia. You can feel this in my stories. When I began writing this collection, I wanted to explore the hauntings — of land or person or loved ones — but also, in some weird way, to bring back the ghosts through these stories.

What was your response to a recent review in The New York Times that was unfairly harsh to your book?

It was incredibly disappointing to read the review. The NYT is a prominent publication. And it’s a review that I have been waiting for. For me, it was an honour to have been considered for the NYT book review. When I read it, I found that it was more than just a negative review. There is a paragraph in which the reviewer says something about the formal experimentation at the cost of the substance of the story. I am completely fine about it. That’s actually a concern that I myself had about the stories. So, while it was not great to read it, it’s still a compelling literary argument. It was when I got to this section about fixating on whiteness that I became not just disturbed, but a little bit angry that my book had not been given a very careful reading. It was a very strange comment because there are not too many White characters in my stories; in the 267-page book, maybe 10 or 15 pages figure White characters. To focus on that particular element in the review felt like a misreading, and even dishonest, to me. The reviewer made a comment that when I wanted to signal that a character was bad, I painted it as White. Since I have very few White characters in my stories, it was confusing. And then there was a comment that I paint all the American characters broadly as imperialists. It was again not true because almost all of my American characters are Afghan-Americans. I didn’t understand how I painted them as imperialists.

Finally, in the last paragraph, which was complimentary, he writes that The Haunting of Hajji Hotak is the strongest story in the collection, but he misread the narrator. He thought that the narrator was the son of Hajji Hotak. I think it’s very clear that it was a surveillance agent that didn’t belong to the family. The part that angered me the most was that my book had been entirely misread. There are inaccuracies in the text. It seemed very clear to me that it was not a careful, honest review. It was a repetition of a narrative that I have seen my entire life, which is: to use Afghanistan to refocus on White characters, to refocus on the White soldiers, to refocus and recentre Whiteness itself. It was deeply disappointing.

You were born in Pakistan. Tell us about your visits to Logar and its centrality in your fiction.

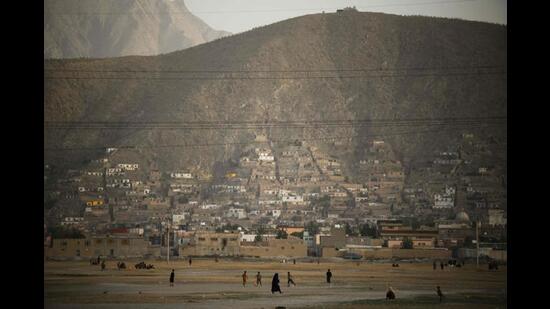

As a child, Afghanistan was a dreamscape for me. Everything I have known about storytelling originated in Logar. Every story that my parents, my grandparents or my aunt told me were about Logar. When I was a child and I returned to Logar for the first time at the age of six, there was something about the location that seemed unreal to me from the very beginning. But then, actually going to Logar, living there and meeting the people was a completely different experience. It altered my conception of Logar. I completely fell in love with it. I was immediately enraptured by the new location, with the orchards and the streets and the mountains always looming in the distance. All my cousins lived over there. All the new friends I had to make spoke the same language as me and seemed to understand my own position.

When we left, it was difficult for me even as a small child. I would think about Logar all the time. And when we came back again after I had turned 12, there was a similar sense of longing and loss. I felt an intense bond with the location as well. Since then, I have been going back every few years or so. So, while it began as a land or as a story or a dreamscape, it became real to me very quickly. I was visiting quite often; I was doing historical research on Logar. I was looking through the landscape. I would talk to my father about how everything had come together initially in terms of geography. So, in that sense, it was also important for me to represent the very real issues, the actual material reality of what was going on in Logar during the Soviet invasion and the American occupation. For me, the balancing of the fantastical and of the very real is important. I want to make sure that both of those elements are balanced in one way or another in my stories. Logar is very dear to me; I spent a lot of time there, both physically and also a lot in my head. And I will continue to write about it.

What was your response to the fall of Kabul to Talibans?

It was an intensely nerve-wracking time. I got a lot of calls and messages from my family back home in Logar and Kabul. They were very worried. There was a lingering fear when the Mujahideen took Kabul after the fall of the Communist-backed government. After that, intense carnage and massive civil war unfolded. Horrible atrocities were committed on all sides. For many of my family members, there was a desperate need to get out of the country. Even today, things are not going well. It’s a very dire situation, whether it’s about Taliban policies with the girls’ schools or the continuing of the sanctions by the US which have completely levelled the economy. Last month, my wife visited Kabul, where she has spent most of her life. She said to me that the poverty she saw there now was more acute than it has ever been. People are starving on the streets. Just a couple of months ago, they had jobs. But now they are forced to live on the streets, uncertain of where their next meal will come from. It’s an incredibly desperate situation. It’s being made worse by the policies of the current regime in Afghanistan, and also by the Biden-led US administration. It’s difficult to watch what is going on there. We keep hoping that at some point the Biden administration is going to lift the sanctions, that he is going to have some sense of mercy upon these poor people, but it’s more likely that it’s not going to happen. The Afghan-American community in the States have been making different efforts, figuring out how to get Afghans out of the country, and also how to get money and resources into the country through fund raisers and food drives, etc. But these efforts seem like the bandage on the bullet wound.

Could you name some young writers from Afghanistan writing fiction?

There is not too much fiction writing from Afghanistan. Many books that are being published and given publicity are written by White Americans and White Europeans. It’s very rare that an Afghan living inside Afghanistan writes about his/her home. It is also very rare to see fiction by Afghani diaspora community in Europe and the US. I hope that as the Afghani diaspora begins to get more and more embedded with the literary industry here, it will give opportunities to Afghan writers throughout the world, especially Afghan writers back home. There is an Afghan writer called Aria Aber, who has come out with a beautiful poetry collection, Hard Damage. It is a breathtaking book, with words and images that I found devastating. She is currently working on a novel. There is another Afghan-American writer called Sahar Muradi, who is also a very talented poet. I do hope that in the coming years, as I continue to develop my own career as a writer, fiction writers back home are going to be given more chances to publish their work. There must be so much talent there, but for the lack of opportunity or spotlight or because of the war itself, they have not been able to come to the fore. I always wonder how many literary geniuses would have been lost because of the circumstances of war or because they had to spend their entire lives working physical labour in order to keep their families alive. I hope it changes in the future and there is more fiction writing from Afghanistan.

Nawaid Anjum is an independent journalist. He lives in New Delhi.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading