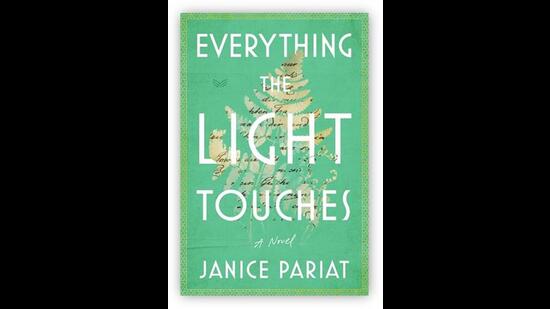

Janice Pariat: ‘You bring people back to life through your stories’

Your new book is grand and audacious. You’ve placed real life historical figures, Goethe and Linnaeus, alongside fictional ones. While separated by centuries and geographies, they are linked by similar philosophies. Collectively, they share a deep connect with the world of plants. What was the germination point of this book?

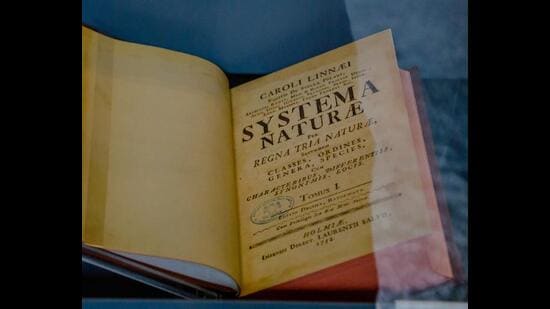

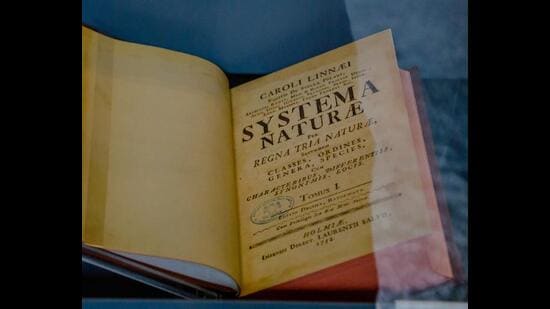

The idea began as a tiny seed in a garden in the UK in 2014, which to our post-pandemic selves feels almost as long ago as the 1700s! I came across this section on the extraordinary lives of women botanists from the Victorian and Edwardian ages. Fascinated by this cluster of feisty women, I wondered if I could imagine a story about a botanist travelling to India. The book began in the true spirit of enquiry; what would she be looking for? Why would she travel to these parts? Simultaneously, I came upon Goethean science while conversing with a friend studying at Schumacher College. Much like Evie in the book, I was curious by this refreshing way of seeing and understanding the world. Both these pieces came together naturally. At the heart of the narrative is Carl Linnaeus, botanist and taxonomist, acting as a counterpoint and a reminder that we exist in a post-Linnaean world, one that has inherited his way of categorising and labelling everything.

My interest lies at the intersection of botany and philosophy, in the belief that the way you see a plant is the way you see the world. One can see it in the Linnaean way as a collection of parts — leaf, flower, root — that make up the whole. But in the Goethean “all is leaf” way, or in Shai’s explorations of the indigenous, it means to see in wholeness. So botany serves as an important metaphor, a way of exploring these different ways of seeing the world.

Light is both imagery and metaphor in the book. In the North-Eastern jungles, there’s lushness deepening into a mysterious dark. Evie’s ship journey carries a sepia tone. The narratives are distinctly atmospheric: Goethe’s account soars exuberantly as he immerses himself in late 18th century Italy, where the ambience is light and airy. Evie faces the predicaments of a botany-learning Edwardian lady who dares the unimaginable in 19th century India. How did you capture the precise essence of each era?

I wish I could say that I travelled in all of their footsteps! Like Goethe, I’ve deeply loved being in Rome. There’s a certain kind of light, an energy and historicity that it possesses which amazes and inspires me. The travel journals I worked with about his Flight to Italy, helped me put together that time in his life. It was a couple of creative and carefree years bathed in that beautiful light, not only because it was Italy, but it was the art that he was seeing, plants he was discovering, the ideas that shone through. So the light works at many levels, the light of a place, a person, of knowledge, of learning new things, of being ever curious. Light is fundamental to life really! It encompasses the novel in an abundance of ways. A lot of research went into Evie’s ship sojourn, since I’ve never been on one. The endeavour was to keep it clutter-free, let the words breathe, and trust the reader’s imagination to do the rest. That’s been my greatest learning from writing historical fiction. The travel in Evie and Shai’s segments are greatly inspired by my journeys back home, trails I’ve known, forests I’ve wandered through, the people I’ve loved and visited in the villages outside Shillong. The nanny Shai visits is from my own childhood. Oiñ, who brought up my sister and me, was my first story teller. In some ways this novel is also for her. Shai visiting her was in some ways me visiting her. You bring people back to life through your stories.

Shai grapples significantly with the question of identity; she’s Christian, has spent her growing years in Shillong and goes back and forth. She then plunges into this impulsive journey into the heart of her land. Is there a kindredness that you feel with her? What does identity mean to you?

In the most tangible way, Shai’s journey echoes mine in some ways: moving away, returning time and again to this complicated place we call home. Her confusion is mine: where am I really meant to be, should I return home or make somewhere else home; are they all not home? But then I feel resonance with all my characters, perhaps less so with Linnaeus, but definitely with Evie and Goethe. Evie’s love of adventure, her spirit of exploration, the courage with which she sets out into the world. With Goethe there is resonance with the idea that he expresses to his companions, “One must be either this or that… poet or scientist… not both, and not anything more.” Often there are labels placed on us: a woman writer, a woman writer from the North-East, etc. It’s tricky, because to identify as something is also to find a certain kind of fixity that restricts, rather than imagining the multitudes a person can be, that they can carry abundance within them and it need not fit within one little box.

An inherent pride of language comes through your writing. Shai’s story weaves in bits of Khasi that have deep-rooted cultural connotations too. How important is knowledge of language to you?

I speak Khasi and can read it. It’s an important presence in the Shai narrative and part of Evie’s. It has had a very rich and distinguished oral tradition. Script was introduced by the missionaries when they arrived in the mid-1800s. An intervention like that changes the texture of the language. Script also tends to fix language visually, in lines or sentences. So the tussle between ways of seeing spills onto the linguistic front as well: the fixity of script versus the fluidity of orality. The narrative also mentions memory and remembrance, which is of the utmost importance in an oral culture. If one doesn’t commit to memory and tell those stories, knowledge dies with you. The nong kñia’s tales are what bind the community in Mawmalang.

The narrative opens out like a whorl, moving inwards from the contemporary toward a historical core, and back into the light of today. What shaped the aesthetic of this structure?

I’d never worked on anything this long and unwieldy. We looked at options, but this kind of structure which nestles one story within another story cradling another one, is what seemed to resonate best with the content of the book. Despite being removed in time or geography, an interconnectedness binds these narratives. At some level they are happening in the here and now, which is why I also used the present tense. We live in a world of exceedingly unequal stories, where some are touted as more important simply because they come from certain parts of the world or cultures, while others are seen as less authentic or authoritative. Therein lay the motivation to place these exceedingly “unequal” stories together, to say that this story is as crucial as this one, and has a way of affecting the other.

What are the reasons behind the choice of stylistic elements in the Linnaeus section?

Linnaeus comes as a shock in the book. His work being the genesis of my book, I spent a lot of time researching him. I never dreamt I would end up reading copiously on botanical/scientific matters! Working his world view into the story was essential because otherwise the other stories hang loose without the “stem” or the “spine”. He was such an assiduous list-maker that in format his writing looks like poetry on the page. The source text I focused on was his 1811 travel memoir, Tour in Lapland. I used a form of poetry called erasure: deliberately and visibly erasing parts of a pre-existing text, and coming up with a new one. I reworked the journal entries in his travel memoir, creating poetry that echoed the way his books looked. A lot of the poems are instruction poetry – “Enjoy the weather… Watch animals grazing… Make a description…”, “The end of travel must be to depict nature more accurately than anyone else.”

ETLT is thematically rich; discarding labels and taxonomies, or women leading lives beyond convention, or the discord between the old and new, tradition versus progress. How challenging was it to weave together so many threads to make it an organic whole?

While working on a project this vast, realisation dawns that everything is connected, however cliched that sounds. That even placing a character like Goethe on the page draws forth a wealth of elements: he is a poet, traveller, playwright, philosopher, lover, companion… I let my characters unrestrained on the page, allowing them to bring in their multitudes. All that is left to me is to then flesh out, structure and sculpt. Evie struggles to be unconstrained, watching men set off to follow their passion. Then suddenly she is free, to be herself, do what she wants. It took me the longest to find Shai’s voice. Sometimes the closer the characters are to ourselves, the harder they are to write about. She was in search of herself, her place within the vastness of the universe. And which is why her tale cradles the book; she offers us that vastness of long perspective, to say that, look at us, we are all stardust. We come from the very first atoms of the universe. And so, where do these divisions lie, where do boundaries lie.

Read more: Review – Everything the Light Touches by Janice Pariat

What is your personal relationship with the natural world?

In our quotidian lives we aren’t always attuned to the ways in which the natural world thrives. The point at which something shifted was the lockdown when we were constrained in an unprecedented way. I was in a little flat with a garden which during those months became my whole world. An intimate relationship evolved between my plants and me. I noticed how despite being rooted they’re far more connected to the world around them. in tune with shifting seasons, light, shade, sunshine. It altered the way I began seeing a forest or wildflowers. The lockdown also sent me home and so I spent a lot more time in the hills of Meghalaya.

What’s next?

I’m looking to work on a novella that serves thematically as a companion to my previous book, Nine-chambered Heart, which looks at relationships, desire, and love under a microscope. Something less ambitious in length for now!

Sonali Mujumdar is an independent journalist. She lives in Mumbai

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Your new book is grand and audacious. You’ve placed real life historical figures, Goethe and Linnaeus, alongside fictional ones. While separated by centuries and geographies, they are linked by similar philosophies. Collectively, they share a deep connect with the world of plants. What was the germination point of this book?

The idea began as a tiny seed in a garden in the UK in 2014, which to our post-pandemic selves feels almost as long ago as the 1700s! I came across this section on the extraordinary lives of women botanists from the Victorian and Edwardian ages. Fascinated by this cluster of feisty women, I wondered if I could imagine a story about a botanist travelling to India. The book began in the true spirit of enquiry; what would she be looking for? Why would she travel to these parts? Simultaneously, I came upon Goethean science while conversing with a friend studying at Schumacher College. Much like Evie in the book, I was curious by this refreshing way of seeing and understanding the world. Both these pieces came together naturally. At the heart of the narrative is Carl Linnaeus, botanist and taxonomist, acting as a counterpoint and a reminder that we exist in a post-Linnaean world, one that has inherited his way of categorising and labelling everything.

My interest lies at the intersection of botany and philosophy, in the belief that the way you see a plant is the way you see the world. One can see it in the Linnaean way as a collection of parts — leaf, flower, root — that make up the whole. But in the Goethean “all is leaf” way, or in Shai’s explorations of the indigenous, it means to see in wholeness. So botany serves as an important metaphor, a way of exploring these different ways of seeing the world.

Light is both imagery and metaphor in the book. In the North-Eastern jungles, there’s lushness deepening into a mysterious dark. Evie’s ship journey carries a sepia tone. The narratives are distinctly atmospheric: Goethe’s account soars exuberantly as he immerses himself in late 18th century Italy, where the ambience is light and airy. Evie faces the predicaments of a botany-learning Edwardian lady who dares the unimaginable in 19th century India. How did you capture the precise essence of each era?

I wish I could say that I travelled in all of their footsteps! Like Goethe, I’ve deeply loved being in Rome. There’s a certain kind of light, an energy and historicity that it possesses which amazes and inspires me. The travel journals I worked with about his Flight to Italy, helped me put together that time in his life. It was a couple of creative and carefree years bathed in that beautiful light, not only because it was Italy, but it was the art that he was seeing, plants he was discovering, the ideas that shone through. So the light works at many levels, the light of a place, a person, of knowledge, of learning new things, of being ever curious. Light is fundamental to life really! It encompasses the novel in an abundance of ways. A lot of research went into Evie’s ship sojourn, since I’ve never been on one. The endeavour was to keep it clutter-free, let the words breathe, and trust the reader’s imagination to do the rest. That’s been my greatest learning from writing historical fiction. The travel in Evie and Shai’s segments are greatly inspired by my journeys back home, trails I’ve known, forests I’ve wandered through, the people I’ve loved and visited in the villages outside Shillong. The nanny Shai visits is from my own childhood. Oiñ, who brought up my sister and me, was my first story teller. In some ways this novel is also for her. Shai visiting her was in some ways me visiting her. You bring people back to life through your stories.

Shai grapples significantly with the question of identity; she’s Christian, has spent her growing years in Shillong and goes back and forth. She then plunges into this impulsive journey into the heart of her land. Is there a kindredness that you feel with her? What does identity mean to you?

In the most tangible way, Shai’s journey echoes mine in some ways: moving away, returning time and again to this complicated place we call home. Her confusion is mine: where am I really meant to be, should I return home or make somewhere else home; are they all not home? But then I feel resonance with all my characters, perhaps less so with Linnaeus, but definitely with Evie and Goethe. Evie’s love of adventure, her spirit of exploration, the courage with which she sets out into the world. With Goethe there is resonance with the idea that he expresses to his companions, “One must be either this or that… poet or scientist… not both, and not anything more.” Often there are labels placed on us: a woman writer, a woman writer from the North-East, etc. It’s tricky, because to identify as something is also to find a certain kind of fixity that restricts, rather than imagining the multitudes a person can be, that they can carry abundance within them and it need not fit within one little box.

An inherent pride of language comes through your writing. Shai’s story weaves in bits of Khasi that have deep-rooted cultural connotations too. How important is knowledge of language to you?

I speak Khasi and can read it. It’s an important presence in the Shai narrative and part of Evie’s. It has had a very rich and distinguished oral tradition. Script was introduced by the missionaries when they arrived in the mid-1800s. An intervention like that changes the texture of the language. Script also tends to fix language visually, in lines or sentences. So the tussle between ways of seeing spills onto the linguistic front as well: the fixity of script versus the fluidity of orality. The narrative also mentions memory and remembrance, which is of the utmost importance in an oral culture. If one doesn’t commit to memory and tell those stories, knowledge dies with you. The nong kñia’s tales are what bind the community in Mawmalang.

The narrative opens out like a whorl, moving inwards from the contemporary toward a historical core, and back into the light of today. What shaped the aesthetic of this structure?

I’d never worked on anything this long and unwieldy. We looked at options, but this kind of structure which nestles one story within another story cradling another one, is what seemed to resonate best with the content of the book. Despite being removed in time or geography, an interconnectedness binds these narratives. At some level they are happening in the here and now, which is why I also used the present tense. We live in a world of exceedingly unequal stories, where some are touted as more important simply because they come from certain parts of the world or cultures, while others are seen as less authentic or authoritative. Therein lay the motivation to place these exceedingly “unequal” stories together, to say that this story is as crucial as this one, and has a way of affecting the other.

What are the reasons behind the choice of stylistic elements in the Linnaeus section?

Linnaeus comes as a shock in the book. His work being the genesis of my book, I spent a lot of time researching him. I never dreamt I would end up reading copiously on botanical/scientific matters! Working his world view into the story was essential because otherwise the other stories hang loose without the “stem” or the “spine”. He was such an assiduous list-maker that in format his writing looks like poetry on the page. The source text I focused on was his 1811 travel memoir, Tour in Lapland. I used a form of poetry called erasure: deliberately and visibly erasing parts of a pre-existing text, and coming up with a new one. I reworked the journal entries in his travel memoir, creating poetry that echoed the way his books looked. A lot of the poems are instruction poetry – “Enjoy the weather… Watch animals grazing… Make a description…”, “The end of travel must be to depict nature more accurately than anyone else.”

ETLT is thematically rich; discarding labels and taxonomies, or women leading lives beyond convention, or the discord between the old and new, tradition versus progress. How challenging was it to weave together so many threads to make it an organic whole?

While working on a project this vast, realisation dawns that everything is connected, however cliched that sounds. That even placing a character like Goethe on the page draws forth a wealth of elements: he is a poet, traveller, playwright, philosopher, lover, companion… I let my characters unrestrained on the page, allowing them to bring in their multitudes. All that is left to me is to then flesh out, structure and sculpt. Evie struggles to be unconstrained, watching men set off to follow their passion. Then suddenly she is free, to be herself, do what she wants. It took me the longest to find Shai’s voice. Sometimes the closer the characters are to ourselves, the harder they are to write about. She was in search of herself, her place within the vastness of the universe. And which is why her tale cradles the book; she offers us that vastness of long perspective, to say that, look at us, we are all stardust. We come from the very first atoms of the universe. And so, where do these divisions lie, where do boundaries lie.

Read more: Review – Everything the Light Touches by Janice Pariat

What is your personal relationship with the natural world?

In our quotidian lives we aren’t always attuned to the ways in which the natural world thrives. The point at which something shifted was the lockdown when we were constrained in an unprecedented way. I was in a little flat with a garden which during those months became my whole world. An intimate relationship evolved between my plants and me. I noticed how despite being rooted they’re far more connected to the world around them. in tune with shifting seasons, light, shade, sunshine. It altered the way I began seeing a forest or wildflowers. The lockdown also sent me home and so I spent a lot more time in the hills of Meghalaya.

What’s next?

I’m looking to work on a novella that serves thematically as a companion to my previous book, Nine-chambered Heart, which looks at relationships, desire, and love under a microscope. Something less ambitious in length for now!

Sonali Mujumdar is an independent journalist. She lives in Mumbai

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading