Killer crabs and bad leprechauns: how the best book blurbs excite our brains | Books

The chances are that you have read more blurbs on books than actual books. Perhaps you have even glanced at one I wrote: I’ve been a copywriter in publishing for 25 years, crafting those miniature stories that aim to distil a book’s magic and connect with readers. Part compression, part come-on, blurbs can also, as I found when I wrote a book about them, open up a world of literary history and wordy joy. Here are some things I discovered.

1 Blurbs mean hype

We roll our eyes at the modern cliches of publishing: the “deeply moving”, “unputdownable tour de force”, the “dazzling”, “luminous”, “sparkling” and “searing”. But it was ever thus. The word “blurb” was coined as a lampoon on literary guff in a 1907 promotional dust jacket by author Frank Gelett Burgess for his book Are You a Bromide? (“bromide” meant a frightful bore). The jacket features a bold-looking dame called “Miss Belinda Blurb in the act of blurbing,” who tells us, among other things, “Yes, this is a BLURB!” and ends with the dubious statement: “This Book is the Proud Purple Penultimate!!”

2 There have always been blurb haters

JD Salinger refused to have any words on his book jackets other than the title and his name. Jeanette Winterson burned her own books on social media in 2021 because she hated the “cosy little domestic” blurbs on their revamped covers. Joe Orton was sent to prison for defacing library books with, among other things, outrageous fake blurbs. A copywriter colleague of mine once had a blurb torn up in front of him by an irate editor, while another made him write 21 different versions for a popular novel.

3 The best authors wrote them

George Orwell worried over his blurbs in detail with his editor, and his original description of Nineteen Eighty-Four as “the history of a revolution that went wrong” is still used on many editions today. The Italian author Roberto Calasso, who beautifully dubbed the blurb “a letter to a stranger”, wrote hundreds of blurbs for the publishing company Adelphi, and even produced a book of them. TS Eliot noted “what a difficult art blurb-writing is”, and sweated over countless blurbs for Faber – although I doubt his interpretation of Robert Graves’s The White Goddess as “a prodigious, monstrous, stupefying, indescribable book” would get past a marketing department today.

4 Blurbs are old

The earliest known dust jacket, for an 1830 gift book, Friendship’s Offering, features a blurb telling us: “This is Affection’s Tribute”. But before then, prototype blurbs graced the title pages of early books: Robinson Crusoe trumpets the adventures to be found inside, including “PYRATES”! Even in Ancient Rome, the poet Martial’s dedications at the beginning of his books assured readers of their quality, in what Calasso called the “noble forebears” of blurbs.

5 Old blurbs are unhinged

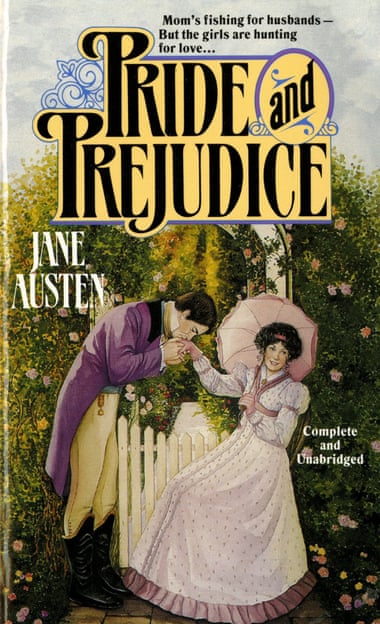

Most blurbs written more than 30 years ago now sound highly eccentric. Many don’t want to be liked: the anti-blurb on an elderly paperback of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory informs us that: “A baleful vulture of doom hovers over this modern crucifixion story.” Some bear little or no resemblance to the books they describe, such as the gloriously tin-eared 1990s Tor editions of Jane Austen’s novels. “Mom’s fishing for husbands – but the girls are hunting for love” is the sell on Pride and Prejudice.

Horror blurbs, especially those on the night-black Pan paperbacks found in holiday cottages, are their own special brand of nonsense, whether summoning up killer crabs (“A bloody carnage of human flesh on an island beachhead!”) or psychotic leprechauns (“They speak German. They carry whips…”).

6 Blurbs need good hooks

Forget Anna Karenina, Moby-Dick or those boats beating ceaselessly in The Great Gatsby. For my money, “Which one of you bitches is my mother?”, from Shirley Conran’s 1980s bonkbuster Lace, is probably the greatest line in the history of the written word. It has also graced every incarnation of the book’s blurb since it was published. I also like to think the blurb’s depiction of thrusting ambition – “four women who took life as they found it and dared to make it a success” – inspired my decision to stay in the same job for a quarter of a century.

7 Bookshops love good blurbs

Copywriters had their time in the sun when, after the first Covid lockdown, shops displayed books with back covers facing outwards so customers wouldn’t have to turn them over. “At last, this is my moment!” I thought. It also showed, of course, that readers really want to know what a book is about. Those few moments it takes to skim the blurb – some estimate 30 seconds at most – can help to make or break a title’s fortunes.

8 Blurbs send signals

Among comforting thrills of genre fiction, familiar sensations matter. Blurbs send specific signals, attracting voracious readers with cues and tropes they anticipate – for example, “Germany, 1945” on a historical thriller. The jeopardy and jabbing sentences of the crime novel. The promise of a twist unlike any we’ve read before. And, of course, the trailing ellipsis …

9 The science of persuasion

There are things that writers have always suspected. An emotional hook, concrete imagery, simplicity, a mystery withheld, a story: these entice readers and, according to psychologists, create the most activity in our brains. Read a blurb, or any persuasive copy, and feel your neurons fire with joy.

10 Blurbs teach brevity

Writing briefly means every word must earn its place. Use fewer and make them better. Don’t make the reader do the hard work; be on their side. Never be boring. Ask, why should anybody care? There are more tips inside my book. (It’s an unputdownable tour de force.)

The chances are that you have read more blurbs on books than actual books. Perhaps you have even glanced at one I wrote: I’ve been a copywriter in publishing for 25 years, crafting those miniature stories that aim to distil a book’s magic and connect with readers. Part compression, part come-on, blurbs can also, as I found when I wrote a book about them, open up a world of literary history and wordy joy. Here are some things I discovered.

1 Blurbs mean hype

We roll our eyes at the modern cliches of publishing: the “deeply moving”, “unputdownable tour de force”, the “dazzling”, “luminous”, “sparkling” and “searing”. But it was ever thus. The word “blurb” was coined as a lampoon on literary guff in a 1907 promotional dust jacket by author Frank Gelett Burgess for his book Are You a Bromide? (“bromide” meant a frightful bore). The jacket features a bold-looking dame called “Miss Belinda Blurb in the act of blurbing,” who tells us, among other things, “Yes, this is a BLURB!” and ends with the dubious statement: “This Book is the Proud Purple Penultimate!!”

2 There have always been blurb haters

JD Salinger refused to have any words on his book jackets other than the title and his name. Jeanette Winterson burned her own books on social media in 2021 because she hated the “cosy little domestic” blurbs on their revamped covers. Joe Orton was sent to prison for defacing library books with, among other things, outrageous fake blurbs. A copywriter colleague of mine once had a blurb torn up in front of him by an irate editor, while another made him write 21 different versions for a popular novel.

3 The best authors wrote them

George Orwell worried over his blurbs in detail with his editor, and his original description of Nineteen Eighty-Four as “the history of a revolution that went wrong” is still used on many editions today. The Italian author Roberto Calasso, who beautifully dubbed the blurb “a letter to a stranger”, wrote hundreds of blurbs for the publishing company Adelphi, and even produced a book of them. TS Eliot noted “what a difficult art blurb-writing is”, and sweated over countless blurbs for Faber – although I doubt his interpretation of Robert Graves’s The White Goddess as “a prodigious, monstrous, stupefying, indescribable book” would get past a marketing department today.

4 Blurbs are old

The earliest known dust jacket, for an 1830 gift book, Friendship’s Offering, features a blurb telling us: “This is Affection’s Tribute”. But before then, prototype blurbs graced the title pages of early books: Robinson Crusoe trumpets the adventures to be found inside, including “PYRATES”! Even in Ancient Rome, the poet Martial’s dedications at the beginning of his books assured readers of their quality, in what Calasso called the “noble forebears” of blurbs.

5 Old blurbs are unhinged

Most blurbs written more than 30 years ago now sound highly eccentric. Many don’t want to be liked: the anti-blurb on an elderly paperback of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory informs us that: “A baleful vulture of doom hovers over this modern crucifixion story.” Some bear little or no resemblance to the books they describe, such as the gloriously tin-eared 1990s Tor editions of Jane Austen’s novels. “Mom’s fishing for husbands – but the girls are hunting for love” is the sell on Pride and Prejudice.

Horror blurbs, especially those on the night-black Pan paperbacks found in holiday cottages, are their own special brand of nonsense, whether summoning up killer crabs (“A bloody carnage of human flesh on an island beachhead!”) or psychotic leprechauns (“They speak German. They carry whips…”).

6 Blurbs need good hooks

Forget Anna Karenina, Moby-Dick or those boats beating ceaselessly in The Great Gatsby. For my money, “Which one of you bitches is my mother?”, from Shirley Conran’s 1980s bonkbuster Lace, is probably the greatest line in the history of the written word. It has also graced every incarnation of the book’s blurb since it was published. I also like to think the blurb’s depiction of thrusting ambition – “four women who took life as they found it and dared to make it a success” – inspired my decision to stay in the same job for a quarter of a century.

7 Bookshops love good blurbs

Copywriters had their time in the sun when, after the first Covid lockdown, shops displayed books with back covers facing outwards so customers wouldn’t have to turn them over. “At last, this is my moment!” I thought. It also showed, of course, that readers really want to know what a book is about. Those few moments it takes to skim the blurb – some estimate 30 seconds at most – can help to make or break a title’s fortunes.

8 Blurbs send signals

Among comforting thrills of genre fiction, familiar sensations matter. Blurbs send specific signals, attracting voracious readers with cues and tropes they anticipate – for example, “Germany, 1945” on a historical thriller. The jeopardy and jabbing sentences of the crime novel. The promise of a twist unlike any we’ve read before. And, of course, the trailing ellipsis …

9 The science of persuasion

There are things that writers have always suspected. An emotional hook, concrete imagery, simplicity, a mystery withheld, a story: these entice readers and, according to psychologists, create the most activity in our brains. Read a blurb, or any persuasive copy, and feel your neurons fire with joy.

10 Blurbs teach brevity

Writing briefly means every word must earn its place. Use fewer and make them better. Don’t make the reader do the hard work; be on their side. Never be boring. Ask, why should anybody care? There are more tips inside my book. (It’s an unputdownable tour de force.)