Maus Now: Selected Writing, edited by Hillary Chute review – the Maus that made history | Essays

This job has taught me to be wary of meeting my heroes, but when I interviewed Art Spiegelman in New York in 2011, it really was one of the great days. In his SoHo studio, the air thick with cigarette smoke and whatever strange substance old paper quietly emits (the place groaned with books), he and I talked long and hard about Maus, then shortly to celebrate its 25th birthday, and every moment was – for me, at least – completely thrilling. I’d long wondered about Spiegelman’s daring in the matter of his famous comic. How on earth had he done it, committing to paper what felt at the time like a kind of blasphemy? But sitting opposite him, I think I understood. In conversation, certainty had only to appear on the horizon for ambivalence to wrestle it to the ground – and vice versa. He simply had to work stuff out. I doubt he could have resisted making Maus even if he’d tried.

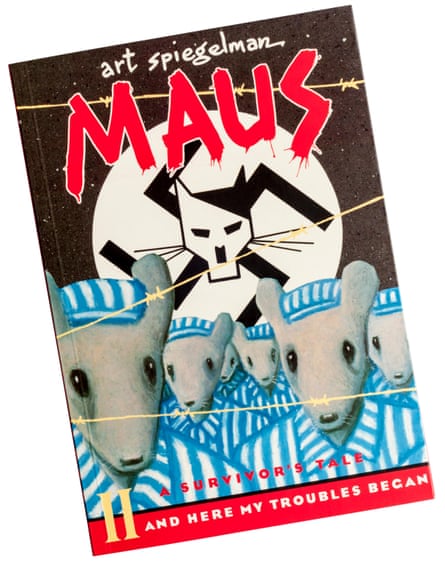

I guess there must still be some people out there who don’t know about Spiegelman’s masterwork. So perhaps I’d better explain. The only comic ever to win a Pulitzer prize, Maus is a two-volume graphic novel about the Holocaust. Based on interviews with his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz, it depicts Jews as mice, Nazis as cats and Poles as pigs, though the source of the shock it caused when it came out (Maus I in 1986, and Maus II in 1991) lay more in its refusal to sanctify the survivor than in its anthropomorphism. The Vladek we see living in Queens with his second wife, Mala – the book has two time frames, past and present – is a parsimonious bully and a racist, a man his adult son can tolerate only when they’re discussing the camps. As Spiegelman put it when he spoke to me: “This is the oddness of it. Auschwitz became for us a safe place: a place where he would talk and I would listen.” (Vladek died in 1982; Spiegelman’s mother, Anja, another survivor, had killed herself in 1968.)

Naturally, Maus has been much written about down the decades, not least in recent months (in 2021, a school board in Tennessee decided to ban it from an English curriculum; the outcry that followed led to it selling out on Amazon). Spiegelman’s paradigm-shifting book appeals to so-called serious types in a way most other graphic novels simply do not. But, alas, it has to be said that this isn’t always a good thing. Wading through Maus Now, a new collection of Maus-inspired pieces edited by Hillary Chute, an academic who writes about comics for the New York Times, is a pretty dispiriting experience. So many words expended to so little effect. So much earnestness and showing off! What on earth, I wonder, does Spiegelman make of it? Again, I picture a struggle: a battle between easy flattery and frankly appalled disdain.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

On the plus side, the book includes decent essays by Philip Pullman, the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, and the critic Ruth Franklin (best known as the biographer of Shirley Jackson), and I like its roughly chronological order, a strategy that reveals the way attitudes towards Maus have shifted and settled across the years: Gopnik’s piece dates from 1987, and in it, he’s still agog, wrestling to say intellectually what he knows in his heart to be true. There are also some interesting illustrations, not only by Spiegelman, but by those who worked in the tradition of “physiognomic comparison” (making men look like animals, and animals like men) before him, among them the 17th-century Frenchman Charles le Brun and the artists who made The Birds’ Head Haggadah, a 13th century Ashkenazi illuminated manuscript that is a masterpiece of Jewish religious art. But one must cherrypick; American criticism, which comprises the majority of this book, can be so desperately toneless.

It may be the case that Maus Now, medicinal as it often tastes, will send some readers back to the book that inspired it with new and livelier thoughts in their minds – in which case, hooray. But I also think that one aspect of the genius of Spiegelman’s cartoon is that it speaks so loudly for itself. If it is intricate and masterful, it is also severely and audaciously unpatterned. However many times I read Maus, I always close it with the feeling that no more needs to be said.

-

Maus Now, edited by Hillary Chute, is published by Viking (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

This job has taught me to be wary of meeting my heroes, but when I interviewed Art Spiegelman in New York in 2011, it really was one of the great days. In his SoHo studio, the air thick with cigarette smoke and whatever strange substance old paper quietly emits (the place groaned with books), he and I talked long and hard about Maus, then shortly to celebrate its 25th birthday, and every moment was – for me, at least – completely thrilling. I’d long wondered about Spiegelman’s daring in the matter of his famous comic. How on earth had he done it, committing to paper what felt at the time like a kind of blasphemy? But sitting opposite him, I think I understood. In conversation, certainty had only to appear on the horizon for ambivalence to wrestle it to the ground – and vice versa. He simply had to work stuff out. I doubt he could have resisted making Maus even if he’d tried.

I guess there must still be some people out there who don’t know about Spiegelman’s masterwork. So perhaps I’d better explain. The only comic ever to win a Pulitzer prize, Maus is a two-volume graphic novel about the Holocaust. Based on interviews with his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz, it depicts Jews as mice, Nazis as cats and Poles as pigs, though the source of the shock it caused when it came out (Maus I in 1986, and Maus II in 1991) lay more in its refusal to sanctify the survivor than in its anthropomorphism. The Vladek we see living in Queens with his second wife, Mala – the book has two time frames, past and present – is a parsimonious bully and a racist, a man his adult son can tolerate only when they’re discussing the camps. As Spiegelman put it when he spoke to me: “This is the oddness of it. Auschwitz became for us a safe place: a place where he would talk and I would listen.” (Vladek died in 1982; Spiegelman’s mother, Anja, another survivor, had killed herself in 1968.)

Naturally, Maus has been much written about down the decades, not least in recent months (in 2021, a school board in Tennessee decided to ban it from an English curriculum; the outcry that followed led to it selling out on Amazon). Spiegelman’s paradigm-shifting book appeals to so-called serious types in a way most other graphic novels simply do not. But, alas, it has to be said that this isn’t always a good thing. Wading through Maus Now, a new collection of Maus-inspired pieces edited by Hillary Chute, an academic who writes about comics for the New York Times, is a pretty dispiriting experience. So many words expended to so little effect. So much earnestness and showing off! What on earth, I wonder, does Spiegelman make of it? Again, I picture a struggle: a battle between easy flattery and frankly appalled disdain.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

On the plus side, the book includes decent essays by Philip Pullman, the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, and the critic Ruth Franklin (best known as the biographer of Shirley Jackson), and I like its roughly chronological order, a strategy that reveals the way attitudes towards Maus have shifted and settled across the years: Gopnik’s piece dates from 1987, and in it, he’s still agog, wrestling to say intellectually what he knows in his heart to be true. There are also some interesting illustrations, not only by Spiegelman, but by those who worked in the tradition of “physiognomic comparison” (making men look like animals, and animals like men) before him, among them the 17th-century Frenchman Charles le Brun and the artists who made The Birds’ Head Haggadah, a 13th century Ashkenazi illuminated manuscript that is a masterpiece of Jewish religious art. But one must cherrypick; American criticism, which comprises the majority of this book, can be so desperately toneless.

It may be the case that Maus Now, medicinal as it often tastes, will send some readers back to the book that inspired it with new and livelier thoughts in their minds – in which case, hooray. But I also think that one aspect of the genius of Spiegelman’s cartoon is that it speaks so loudly for itself. If it is intricate and masterful, it is also severely and audaciously unpatterned. However many times I read Maus, I always close it with the feeling that no more needs to be said.

-

Maus Now, edited by Hillary Chute, is published by Viking (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply