Novelist Caleb Azumah Nelson: ‘Why would you put a ceiling on anyone?’ | Books

Chaotic conditions in Peckham: brolly-ruining wind, sudden showers, one of those afternoons when the weather apps show every symbol from sunshine to lightning and leave you to figure it out. Caleb Azumah Nelson, the 29-year-old author and artist whose prose and photographs tend to document life in south London, was meant to be showing me around today. We might have swung by the Peckhamplex cinema, the public library off Rye Lane, maybe getting as far as Morley’s burger bar to the south or Bagel King further north – all of which places Nelson has written about in his beautiful second novel, Small Worlds, a follow-up to 2021’s Open Water, which won the Costa first novel award.

Instead of roaming, as planned, we’re taking shelter from heavy rain under an awning outside Peckham Rye station. Nelson recently spent eight weeks on a writers’ retreat in north-east America. “There was a polar vortex or something,” he says. “It was minus 40. Balaclava weather. My eyelashes actually froze together.” Today’s grey city rain is no great hardship by comparison. We set out to find a cafe he likes on Rye Lane, fighting with our umbrellas all the way.

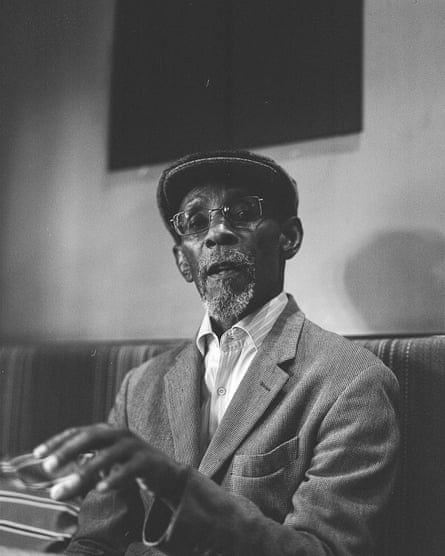

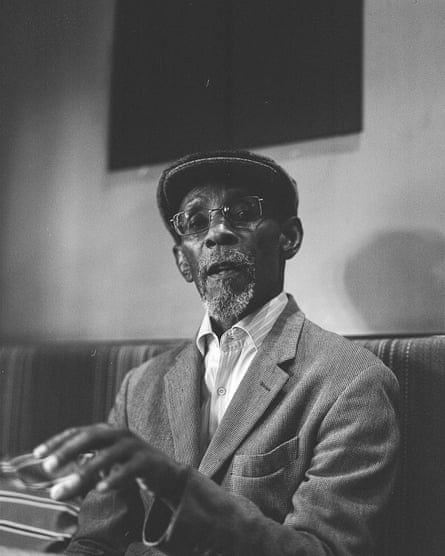

Nelson is tall, handsome, partially bearded, dressed plainly and smartly in dark colours. We’re joined on our walk by a photographer called Ejatu Shaw, who Nelson knows through shared university friends, and who will later take pictures of him for the Observer. Shaw recently got back from a photography tour of Sierra Leone, she says, where she shot on rolls of film that are yet to be developed. She talks about the dread and the excitement of this: having maybe made art, but not being in a position yet to be sure. Nelson immediately understands.

He writes his novels in a similar way, he says. He wakes early, ideally before dawn, when it’s quiet, “trying to get out of my own way,” he calls this. He thinks of fiction as something to be improvised, like jazz, as instinctual as it is planned out. Sometimes he will email himself little notes of encouragement. “Things like, tell this story from the belly.” (The belly, that is, instead of the brain.) Often he’ll put aside a completed work for weeks, resisting the temptation to reread. Like Shaw with her unprocessed rolls of film, Nelson won’t know what he has until some time has passed, and he can approach it fresh. “Nerve-racking. But when I’m writing like this,” he says, “it’s the most honest version of myself. Probably one of the best versions of myself.”

George Saunders, in his avuncular, encouraging way, preaches revision, revision, revision as a fundamental of good fiction. Zadie Smith subscribes to the Kurt Vonnegut method, where you do not progress from one sentence to the next until that sentence is as well-turned as it can be. Sometimes a different approach – faster, looser, woozier – suits an author better. You think of Graham Greene on his 1940s benzedrine benders, racing out two books at a time. Some brilliant contemporary novels, Olivia Laing’s Crudo among them, have been intentionally speed-written to try to capture something raw, less covered in fingerprints, as prose can become after too much reworking. The magic of Nelson’s Small Worlds, which he wrote in three months, is its immediacy, its downhill flow.

“The idea was to make it feel like one long, continuous song,” Nelson says of the book, which is told largely from the perspective of Stephen, a young man on the cusp of his 20s, half in love with a childhood friend called Del, and trying to work out what to do about that. Like Nelson, Stephen is a second-generation British Ghanaian, his family split between south London and Accra. He thinks a lot about the sacrifices made by an older generation who moved from west Africa to the UK before his birth, trying to put together a clearer picture of their severed lives of “movement, migration, burden”. They had to choose “which parts of [their] life to keep,” Nelson writes, “which to let fall away.”

As we find a seat by the window in his favourite Rye Lane cafe, Nelson tells me a story about packing a suitcase before leaving for America, recently, and that chilly writing retreat. “I was only going for two months. But I remember I had this moment, thinking: ‘What should I take? What might I miss?’ It really had me wondering, again, what that process must have been like for my parents’ generation, and for so many people who came here from west Africa and the Caribbean. It got me thinking about how young a lot of them were, only 18 when they made the decision: ‘I will pack a suitcase. I will get on a plane. I’m not gonna see this place I call my home for a while. I’m going to work out how to live in a place that is foreign and might not be welcoming.’ Terrifying,” Nelson says. “Terrifying.”

Within immigrant families, ambition is often a foundational tenet. Those ancestors or relatives who uprooted themselves and came to the UK took a big risk – and there can be a feeling, spoken or otherwise, that subsequent generations had better make their risk worthwhile. I’m telling Nelson about the supreme importance of legal and medical qualifications within my Jewish family when he laughs, claps his hands, and says: “Oh, familiar! Familiar scenes.” We agree, it’s not a small thing to pursue a career in the arts when your parents and grandparents might prefer those professions that are more conventional, and more likely to bring financial reward.

“I don’t know how this works in your family,” Nelson says, “but in mine, stability is a key aspiration.”

Nelson grew up in Bellingham, a few stops south of Peckham Rye on the Sevenoaks train. After going to a local state primary school, Nelson, a besotted reader as a child, “always in libraries, bookshops, staying up super late reading Harry Potter”, won a scholarship place at the fee-paying Alleyn’s school in Dulwich. Though all fees were waived for Nelson, his education was not without costs.

Being a scholarship kid “was a thing in itself. Because there’s a knowledge that you’re not paying.” Mostly, though, Nelson remembers “being one of only four black kids in the year. Which was quite alienating. Kids can be really wonderful. And kids can also be really cruel. They don’t always understand when they’re being cruel; what it might mean to express something that seems an everyday thing to them, but can be hurtful, slanted.”

He loved most of his English teachers. “They pushed me. And believed. And still do.” Not every pupil-teacher interaction was so positive. Nelson slows down his speech, to pick his words with care. “This is not to throw anyone under the bus. This was only a handful of teachers, among a lot of wonderful experiences. But there wasn’t always an understanding that it was possible for me to have the same sense of propulsion [as white students]. There wasn’t always an understanding that I might go for it all as well.”

Being doubted like this as a teenager made him resilient as an adult, he says. (“My instinct on hearing ‘no’ is to think, ‘Well, how are we gonna do this?’”) But latterly, Nelson has started to wonder whether his resilience isn’t as much a wound as an attribute. “Is resilience something you always want? Because resilience implies that you had to go through something, and come out the other side with it… Maybe it’s only now, with perspective and understanding, I can see that actually, maybe, some of what happened back then wasn’t OK.”

Nelson had a session with his therapist on the morning of our interview. The subject of his secondary education came up again. Unexpectedly, he ended up in tears. “It’s only now that I’m beginning to unpack those experiences and think about how they might have, quietly, reverberated through my life.” He is silent for a moment. “Cos how can you not believe in someone? Why would you put a ceiling on anyone? Why would you not afford them possibility? I was a child.”

The various conflicts and contradictions of his secondary education came to a head on a school trip when he was 17. “We were on a school sports tour to Barbados. Which is a ridiculous thing to be able to say, right?” He means, what privilege! “But there we were in Barbados, a majority-black country. And still there was this level of superiority, unconscious, I think – as if, because we were a majority-white group, we were up here.” Nelson raises his hand, over head height. “I remember thinking, even at 17, this is how the world works. And this is how it’s gonna continue to work as I make my way out of this temporary bubble of a scholarship. That trip was a knock on the head. Like, what are you gonna do with your life, when you’re out of here?”

He was a talented basketball player at the time. One day, jumping for a ball, he tangled awkwardly with another player and dislocated his right shoulder. “Twelve weeks to heal. Then, the day I was back playing, I tore it out again.” The second time there wasn’t even any contact. “Someone just held out the ball, and I reached to take it, and pop, just like that.” He’d had dreams of playing in Europe, maybe trying for a sports scholarship at an American university. But those dreams went pop, just like that. In need of a new direction, he started writing prose, in secret at first, continuing throughout a sports science degree at Coventry University. After “years of steady writing I maybe had eight novels on my hard drive. All of them varying degrees of terrible.”

It wasn’t until he was in his mid-20s, living at home in Bellingham again, when he found an agent. A couple of his short stories were published in magazines. One of these, Pray, was shortlisted for the BBC national short story award in 2020. What changed, I ask him, from the years of varyingly terrible novels, to writing fiction that worked? Nelson got better, he thinks, when he started to let his interest in photography and image-creation overlap more deliberately with his writing. He’d been taking photographs since he was a teenager. Working on the book that would become his debut, Open Water, “I would start by imagining an image, then try to transcribe that, everything the image made me feel”.

I ask him if he can give an example of the same process from his second novel, and Nelson mentions one of my favourite scenes, which takes place when Stephen and his family gather to watch the Ghanaian national football team play in a World Cup quarter-final in 2010. This was an infamous, ugly match that ended in disaster for Ghana. One of their opponents, Uruguay’s Luis Suárez, handballed a sure goal off the line in the dying minutes; later, Ghana were eliminated on penalties. When Nelson wrote that scene, he did not rewatch the game, he says. Instead, “I’m seeing a room at my auntie’s house in Catford. A barbecue outside. Six TVs all showing the same match. Everyone wearing their Ghana shirts. This real belief, total faith, almost religious, that we’re gonna win the World Cup. And then the handball. And the anger. Then a groan of disdain. I focused on the space between the anger and the groan. That was the image and the feeling I started with.”

Nelson was hungover, one day in 2019, when Open Water was submitted to publishers. He was working at an Apple Store at the time. He’d been out late the night before at a birthday party. Submission day was spent with his mum, listless, nervous, pacing the family home, craving his preferred hangover cure: “Red velvet cake,” Nelson chuckles. His mum drove him to Marks & Spencer in Bromley to find some. While they were queuing to pay, cake in hand, an email came through from his agent. Nine publishers had made offers. A bidding war was under way. Nelson and his mum drove home dumbstruck.

“It still makes me emotional, thinking about it,” he says. He accepted the biggest offer of the nine, from Viking, part of Penguin Random House, and quit his job. By the time the paperback of Open Water came out in early 2021, Nelson had won or been shortlisted for an enormous number of literary prizes named after writers (the Dylan Thomas, the Betty Trask, the Somerset Maugham, the Gordon Burn, the Desmond Elliott). He also won the Costa first novel award, yelping for joy when he heard. He had a deal with a British production company, Brock Media, to adapt his fiction into multiple screenplays.

Four days after Open Water’s paperback launch, Nelson remembers, he was on a flight to Ghana, to research parts of his second novel. “My paperback came out on a Thursday and I flew out on a Sunday. I really knew I had to take that trip. I don’t know what it was; something deep in my belly.” He hadn’t been back to Accra since family holidays when he was a child. Over time, he had missed the funerals of close relatives, including that of his beloved maternal grandmother, who lived with him in London until he was six. “I don’t know if it’s a place I could call home. But I had this pull to go back. I said to my mum, if I’m gonna write about it, I wanna put my feet on the ground, feel the textures, hear the sounds.”

Nelson took photographs during the trip, a pile of which he has brought along to the cafe on Rye Lane to show me. “This is Mum after getting her hair done, about five days into our trip,” Nelson says, turning to a photo of his mother, sitting in a relative’s home, braided resplendently. We agree that her expression is hard to read. She looks content to be in a familiar place; also, anxious to be about to leave it. I have read the parts of Nelson’s novel that resulted from this Ghana trip, and though it would not be accurate to say that his photos directly accord with his fictional scenes, the pictures and the prose capture a sense of dislocation anxiety – feelings that can be passed down generationally within families, the same as ambition or a desire for stability.

In one stunning chapter, written in the second person, Nelson describes somebody of his father’s generation making a decision to leave Accra, the necessary quickness of the decision, and, decision made, the hurried departure. “When it’s your turn,” Nelson writes, “it’s almost without incident… You spend a day deciding what you will take with you and what you will leave behind. You take the guitar; but you’ll send for the records, it’ll be too expensive to take everything in one go.”

“For me, there was something extra in that Ghana trip,” Nelson says, “a confrontation with a part of myself. There was no looking away.”

Buses roll by outside, including the number 12 that Nelson often used to ride to Nando’s in Camberwell. Whenever the cafe door is pushed open, blasts of wind or rain, or bright sun come through; it keeps changing every few minutes, a perfectly paradoxical London day. There is so much that Nelson loves about this city. But it can be a weird and troubling place to live, especially if you’re someone who looks like he does, taken for “a person not to be trusted”, as he puts it, “even a dangerous person, because of the body that I inhabit”.

He has been stopped-and-searched before. As soon as that happens to you once or twice, Nelson says, you’re always left with the feeling it can and will happen again. “Just trying to be in your everyday. And aware that because you’re young, black, tall, that everyday-ness might be interrupted, you might be closed-in-on… I’ve begun to see it as a sort of grief, a form of loss – and not just my loss, but a collective loss that will have been experienced by so many others. There is a kind of wholeness with which most people get to live their lives that isn’t always afforded to black people. I sometimes wonder, what would a world look like where there’s a sense of care, a sense of grace, just a real sense of humanity that’s afforded to us, too?”

Maybe it’s something he will explore further in future writing. “It can be quite a difficult thing to wrangle with,” Nelson says. “But I’m in a position of luxury, in that I get to write and make art full-time. I recognise that so much of the work I do, whether it ends up as a sentence, or a [photographic] frame, is so much bigger than me. In a world in which so often black people are said to be dangerous, or servile, or ugly, or abject, I have this opportunity to do work that makes black people ask themselves, instead: ‘How do you feel today? And how, today, might you feel beautiful?’”

He will be up early again tomorrow, working at his desk before dawn. (“If I wasn’t a writer I could only be a baker,” Nelson jokes, of his habitual 5am starts.) There are film adaptations of Open Water and Small Worlds under way. A few days after our interview, a short film Nelson wrote, based on one of his short stories, will have its first screening for friends and family. We walk back towards Peckham Rye station, passing a Jamaican takeaway with patties in the window, then a gentrified small-plates restaurant, the Nags Head pub, an Afro-Caribbean mini-mart, all “yams and plantain and kenkey and fufu powder,” as Nelson describes one of these shops in Small Worlds, “garden eggs and okra and Scotch bonnets, dried fish by the box, Supermalt by the crate.”

I’d been meaning to ask him what he missed when he got to his writing retreat in America and finally opened his suitcase. What had he forgotten to pack?

“It’s funny, the thing I ended up missing most wouldn’t have fitted in my suitcase anyway. It’s what my relatives, coming over here from Ghana, would have missed as well.” He gestures at the streets around us. “Community,” Nelson says.

Chaotic conditions in Peckham: brolly-ruining wind, sudden showers, one of those afternoons when the weather apps show every symbol from sunshine to lightning and leave you to figure it out. Caleb Azumah Nelson, the 29-year-old author and artist whose prose and photographs tend to document life in south London, was meant to be showing me around today. We might have swung by the Peckhamplex cinema, the public library off Rye Lane, maybe getting as far as Morley’s burger bar to the south or Bagel King further north – all of which places Nelson has written about in his beautiful second novel, Small Worlds, a follow-up to 2021’s Open Water, which won the Costa first novel award.

Instead of roaming, as planned, we’re taking shelter from heavy rain under an awning outside Peckham Rye station. Nelson recently spent eight weeks on a writers’ retreat in north-east America. “There was a polar vortex or something,” he says. “It was minus 40. Balaclava weather. My eyelashes actually froze together.” Today’s grey city rain is no great hardship by comparison. We set out to find a cafe he likes on Rye Lane, fighting with our umbrellas all the way.

Nelson is tall, handsome, partially bearded, dressed plainly and smartly in dark colours. We’re joined on our walk by a photographer called Ejatu Shaw, who Nelson knows through shared university friends, and who will later take pictures of him for the Observer. Shaw recently got back from a photography tour of Sierra Leone, she says, where she shot on rolls of film that are yet to be developed. She talks about the dread and the excitement of this: having maybe made art, but not being in a position yet to be sure. Nelson immediately understands.

He writes his novels in a similar way, he says. He wakes early, ideally before dawn, when it’s quiet, “trying to get out of my own way,” he calls this. He thinks of fiction as something to be improvised, like jazz, as instinctual as it is planned out. Sometimes he will email himself little notes of encouragement. “Things like, tell this story from the belly.” (The belly, that is, instead of the brain.) Often he’ll put aside a completed work for weeks, resisting the temptation to reread. Like Shaw with her unprocessed rolls of film, Nelson won’t know what he has until some time has passed, and he can approach it fresh. “Nerve-racking. But when I’m writing like this,” he says, “it’s the most honest version of myself. Probably one of the best versions of myself.”

George Saunders, in his avuncular, encouraging way, preaches revision, revision, revision as a fundamental of good fiction. Zadie Smith subscribes to the Kurt Vonnegut method, where you do not progress from one sentence to the next until that sentence is as well-turned as it can be. Sometimes a different approach – faster, looser, woozier – suits an author better. You think of Graham Greene on his 1940s benzedrine benders, racing out two books at a time. Some brilliant contemporary novels, Olivia Laing’s Crudo among them, have been intentionally speed-written to try to capture something raw, less covered in fingerprints, as prose can become after too much reworking. The magic of Nelson’s Small Worlds, which he wrote in three months, is its immediacy, its downhill flow.

“The idea was to make it feel like one long, continuous song,” Nelson says of the book, which is told largely from the perspective of Stephen, a young man on the cusp of his 20s, half in love with a childhood friend called Del, and trying to work out what to do about that. Like Nelson, Stephen is a second-generation British Ghanaian, his family split between south London and Accra. He thinks a lot about the sacrifices made by an older generation who moved from west Africa to the UK before his birth, trying to put together a clearer picture of their severed lives of “movement, migration, burden”. They had to choose “which parts of [their] life to keep,” Nelson writes, “which to let fall away.”

As we find a seat by the window in his favourite Rye Lane cafe, Nelson tells me a story about packing a suitcase before leaving for America, recently, and that chilly writing retreat. “I was only going for two months. But I remember I had this moment, thinking: ‘What should I take? What might I miss?’ It really had me wondering, again, what that process must have been like for my parents’ generation, and for so many people who came here from west Africa and the Caribbean. It got me thinking about how young a lot of them were, only 18 when they made the decision: ‘I will pack a suitcase. I will get on a plane. I’m not gonna see this place I call my home for a while. I’m going to work out how to live in a place that is foreign and might not be welcoming.’ Terrifying,” Nelson says. “Terrifying.”

Within immigrant families, ambition is often a foundational tenet. Those ancestors or relatives who uprooted themselves and came to the UK took a big risk – and there can be a feeling, spoken or otherwise, that subsequent generations had better make their risk worthwhile. I’m telling Nelson about the supreme importance of legal and medical qualifications within my Jewish family when he laughs, claps his hands, and says: “Oh, familiar! Familiar scenes.” We agree, it’s not a small thing to pursue a career in the arts when your parents and grandparents might prefer those professions that are more conventional, and more likely to bring financial reward.

“I don’t know how this works in your family,” Nelson says, “but in mine, stability is a key aspiration.”

Nelson grew up in Bellingham, a few stops south of Peckham Rye on the Sevenoaks train. After going to a local state primary school, Nelson, a besotted reader as a child, “always in libraries, bookshops, staying up super late reading Harry Potter”, won a scholarship place at the fee-paying Alleyn’s school in Dulwich. Though all fees were waived for Nelson, his education was not without costs.

Being a scholarship kid “was a thing in itself. Because there’s a knowledge that you’re not paying.” Mostly, though, Nelson remembers “being one of only four black kids in the year. Which was quite alienating. Kids can be really wonderful. And kids can also be really cruel. They don’t always understand when they’re being cruel; what it might mean to express something that seems an everyday thing to them, but can be hurtful, slanted.”

He loved most of his English teachers. “They pushed me. And believed. And still do.” Not every pupil-teacher interaction was so positive. Nelson slows down his speech, to pick his words with care. “This is not to throw anyone under the bus. This was only a handful of teachers, among a lot of wonderful experiences. But there wasn’t always an understanding that it was possible for me to have the same sense of propulsion [as white students]. There wasn’t always an understanding that I might go for it all as well.”

Being doubted like this as a teenager made him resilient as an adult, he says. (“My instinct on hearing ‘no’ is to think, ‘Well, how are we gonna do this?’”) But latterly, Nelson has started to wonder whether his resilience isn’t as much a wound as an attribute. “Is resilience something you always want? Because resilience implies that you had to go through something, and come out the other side with it… Maybe it’s only now, with perspective and understanding, I can see that actually, maybe, some of what happened back then wasn’t OK.”

Nelson had a session with his therapist on the morning of our interview. The subject of his secondary education came up again. Unexpectedly, he ended up in tears. “It’s only now that I’m beginning to unpack those experiences and think about how they might have, quietly, reverberated through my life.” He is silent for a moment. “Cos how can you not believe in someone? Why would you put a ceiling on anyone? Why would you not afford them possibility? I was a child.”

The various conflicts and contradictions of his secondary education came to a head on a school trip when he was 17. “We were on a school sports tour to Barbados. Which is a ridiculous thing to be able to say, right?” He means, what privilege! “But there we were in Barbados, a majority-black country. And still there was this level of superiority, unconscious, I think – as if, because we were a majority-white group, we were up here.” Nelson raises his hand, over head height. “I remember thinking, even at 17, this is how the world works. And this is how it’s gonna continue to work as I make my way out of this temporary bubble of a scholarship. That trip was a knock on the head. Like, what are you gonna do with your life, when you’re out of here?”

He was a talented basketball player at the time. One day, jumping for a ball, he tangled awkwardly with another player and dislocated his right shoulder. “Twelve weeks to heal. Then, the day I was back playing, I tore it out again.” The second time there wasn’t even any contact. “Someone just held out the ball, and I reached to take it, and pop, just like that.” He’d had dreams of playing in Europe, maybe trying for a sports scholarship at an American university. But those dreams went pop, just like that. In need of a new direction, he started writing prose, in secret at first, continuing throughout a sports science degree at Coventry University. After “years of steady writing I maybe had eight novels on my hard drive. All of them varying degrees of terrible.”

It wasn’t until he was in his mid-20s, living at home in Bellingham again, when he found an agent. A couple of his short stories were published in magazines. One of these, Pray, was shortlisted for the BBC national short story award in 2020. What changed, I ask him, from the years of varyingly terrible novels, to writing fiction that worked? Nelson got better, he thinks, when he started to let his interest in photography and image-creation overlap more deliberately with his writing. He’d been taking photographs since he was a teenager. Working on the book that would become his debut, Open Water, “I would start by imagining an image, then try to transcribe that, everything the image made me feel”.

I ask him if he can give an example of the same process from his second novel, and Nelson mentions one of my favourite scenes, which takes place when Stephen and his family gather to watch the Ghanaian national football team play in a World Cup quarter-final in 2010. This was an infamous, ugly match that ended in disaster for Ghana. One of their opponents, Uruguay’s Luis Suárez, handballed a sure goal off the line in the dying minutes; later, Ghana were eliminated on penalties. When Nelson wrote that scene, he did not rewatch the game, he says. Instead, “I’m seeing a room at my auntie’s house in Catford. A barbecue outside. Six TVs all showing the same match. Everyone wearing their Ghana shirts. This real belief, total faith, almost religious, that we’re gonna win the World Cup. And then the handball. And the anger. Then a groan of disdain. I focused on the space between the anger and the groan. That was the image and the feeling I started with.”

Nelson was hungover, one day in 2019, when Open Water was submitted to publishers. He was working at an Apple Store at the time. He’d been out late the night before at a birthday party. Submission day was spent with his mum, listless, nervous, pacing the family home, craving his preferred hangover cure: “Red velvet cake,” Nelson chuckles. His mum drove him to Marks & Spencer in Bromley to find some. While they were queuing to pay, cake in hand, an email came through from his agent. Nine publishers had made offers. A bidding war was under way. Nelson and his mum drove home dumbstruck.

“It still makes me emotional, thinking about it,” he says. He accepted the biggest offer of the nine, from Viking, part of Penguin Random House, and quit his job. By the time the paperback of Open Water came out in early 2021, Nelson had won or been shortlisted for an enormous number of literary prizes named after writers (the Dylan Thomas, the Betty Trask, the Somerset Maugham, the Gordon Burn, the Desmond Elliott). He also won the Costa first novel award, yelping for joy when he heard. He had a deal with a British production company, Brock Media, to adapt his fiction into multiple screenplays.

Four days after Open Water’s paperback launch, Nelson remembers, he was on a flight to Ghana, to research parts of his second novel. “My paperback came out on a Thursday and I flew out on a Sunday. I really knew I had to take that trip. I don’t know what it was; something deep in my belly.” He hadn’t been back to Accra since family holidays when he was a child. Over time, he had missed the funerals of close relatives, including that of his beloved maternal grandmother, who lived with him in London until he was six. “I don’t know if it’s a place I could call home. But I had this pull to go back. I said to my mum, if I’m gonna write about it, I wanna put my feet on the ground, feel the textures, hear the sounds.”

Nelson took photographs during the trip, a pile of which he has brought along to the cafe on Rye Lane to show me. “This is Mum after getting her hair done, about five days into our trip,” Nelson says, turning to a photo of his mother, sitting in a relative’s home, braided resplendently. We agree that her expression is hard to read. She looks content to be in a familiar place; also, anxious to be about to leave it. I have read the parts of Nelson’s novel that resulted from this Ghana trip, and though it would not be accurate to say that his photos directly accord with his fictional scenes, the pictures and the prose capture a sense of dislocation anxiety – feelings that can be passed down generationally within families, the same as ambition or a desire for stability.

In one stunning chapter, written in the second person, Nelson describes somebody of his father’s generation making a decision to leave Accra, the necessary quickness of the decision, and, decision made, the hurried departure. “When it’s your turn,” Nelson writes, “it’s almost without incident… You spend a day deciding what you will take with you and what you will leave behind. You take the guitar; but you’ll send for the records, it’ll be too expensive to take everything in one go.”

“For me, there was something extra in that Ghana trip,” Nelson says, “a confrontation with a part of myself. There was no looking away.”

Buses roll by outside, including the number 12 that Nelson often used to ride to Nando’s in Camberwell. Whenever the cafe door is pushed open, blasts of wind or rain, or bright sun come through; it keeps changing every few minutes, a perfectly paradoxical London day. There is so much that Nelson loves about this city. But it can be a weird and troubling place to live, especially if you’re someone who looks like he does, taken for “a person not to be trusted”, as he puts it, “even a dangerous person, because of the body that I inhabit”.

He has been stopped-and-searched before. As soon as that happens to you once or twice, Nelson says, you’re always left with the feeling it can and will happen again. “Just trying to be in your everyday. And aware that because you’re young, black, tall, that everyday-ness might be interrupted, you might be closed-in-on… I’ve begun to see it as a sort of grief, a form of loss – and not just my loss, but a collective loss that will have been experienced by so many others. There is a kind of wholeness with which most people get to live their lives that isn’t always afforded to black people. I sometimes wonder, what would a world look like where there’s a sense of care, a sense of grace, just a real sense of humanity that’s afforded to us, too?”

Maybe it’s something he will explore further in future writing. “It can be quite a difficult thing to wrangle with,” Nelson says. “But I’m in a position of luxury, in that I get to write and make art full-time. I recognise that so much of the work I do, whether it ends up as a sentence, or a [photographic] frame, is so much bigger than me. In a world in which so often black people are said to be dangerous, or servile, or ugly, or abject, I have this opportunity to do work that makes black people ask themselves, instead: ‘How do you feel today? And how, today, might you feel beautiful?’”

He will be up early again tomorrow, working at his desk before dawn. (“If I wasn’t a writer I could only be a baker,” Nelson jokes, of his habitual 5am starts.) There are film adaptations of Open Water and Small Worlds under way. A few days after our interview, a short film Nelson wrote, based on one of his short stories, will have its first screening for friends and family. We walk back towards Peckham Rye station, passing a Jamaican takeaway with patties in the window, then a gentrified small-plates restaurant, the Nags Head pub, an Afro-Caribbean mini-mart, all “yams and plantain and kenkey and fufu powder,” as Nelson describes one of these shops in Small Worlds, “garden eggs and okra and Scotch bonnets, dried fish by the box, Supermalt by the crate.”

I’d been meaning to ask him what he missed when he got to his writing retreat in America and finally opened his suitcase. What had he forgotten to pack?

“It’s funny, the thing I ended up missing most wouldn’t have fitted in my suitcase anyway. It’s what my relatives, coming over here from Ghana, would have missed as well.” He gestures at the streets around us. “Community,” Nelson says.