Obituary: Gopi Chand Narang, Urdu scholar and critic

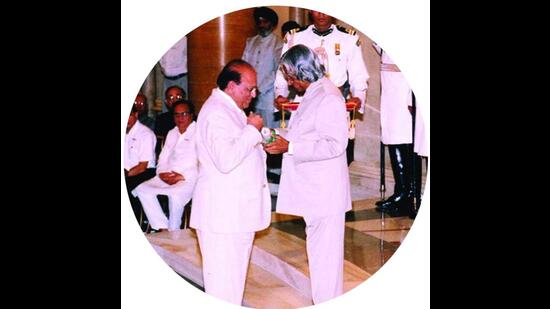

Urdu literary theorist Gopi Chand Narang (born in 1931), who was honoured by both India and Pakistan, died on June 15. His scholarship pegs down two hostile nations, each of which conferred its highest honour on him – he was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 2004 and the Sitar e-Imtiaz in 2012.

Professor Narang wrote more than 70 books in Urdu, English and Hindi. Academic rigour and a profound interest in new criticism, stylistics, semiotics and sociolinguistics run through his work. In a literary journey spread over more than seven decades, he meticulously spelt out a well-defined literary poetics that helped Urdu criticism extricate itself from the bond of theme-centred evaluation.

On the right side of many significant literary trends, his writing reveals his sharp critical insight. He engaged perceptively with different ideological positions without a trace of a totalitarian authorial discourse. He deftly applied Arabic-Persian literary theories, Sanskrit poetics, structuralism and post-structuralism to every genre from the ghazal to fiction. Sakhtiyaat, Pas Sakhtiyat aur Mashriqi Sheriyaat (Structuralism, Post-structuralism and Eastern poetics, 1993), an example of his profound scholarship, gives equal attention to western and eastern poetics. Divided into three sections, the book looks at the concept of language and literature and the construction of reality. It shows how structuralism strikes at the roots of the metaphysical concept of reality. The certitude of literature that mirrors reality owes much to common sense and historicity. Professor Narang judiciously connects Ferdinand de Saussure’s sound pattern of words and psychological phenomena with Prakrta Dhvani (the psychological) and Vaikarta Dhvani (the physical). He also drew parallels between Saussure’s views that language has no positive value except in opposition to something else with the Apoha theory of Buddhist logicians for whom the meaning of a word lies not in its positivity but in the contradistinction of its correlates. Having yoked eastern poetics with structuralism and post-structuralism, he spells out the contours of the new model of criticism. The debate also explores the simultaneous quest for a universal and national identity.

Read more: Interview with Gopi Chand Narang

Professor Narang also deftly used deconstructionism to re-evaluate the whole range of Urdu poetry, including the work of Mir, Ghalib, Iqbal, Faiz, Firaq, Shahryar and Mohammad Alvi, among others.

Mir Taqi Mir’s (1723-1810) nuanced and multisensory poetry is usually read through the prism of his personal life that was mired in deprivation. Less rigorous critics have used terms to do with agony, angst, the deep sense of loss, longing, and the pangs of unrequited love to evaluate Mir’s lucent opus. This has resulted in him being erroneous labelled as a poet of simplicity and emotional flourishes. Always piqued by the cliché ridden critical idiom, Professor Narang’s latest book, The Hidden Garden: Mir Taqi Mir (Penguin Random House, 2021), unravels the various layers of the poet’s “deceptive simplicity”. He seeks to locate Mir in our current epoch of untruth through a close reading of his ghazals. “Mir is not a simple poet by any means. I have tried to unwrap every hidden pathway, every dark trail that zigzags, every footprint that shows something new, and every trajectory that leads to a more hopeful future. Mir is not a poet of unrequited love; his voice reveals and recreates echoes of the medieval age’s soul-searching and the transcendental thought of the bhakti tradition and spirituality that runs parallel to the self-consuming mystic narrative of Mansur and Majnu.”

Review: The Hidden Garden – Mir Taqi Mir by Gopi Chand Narang

Mir’s various phases are studied from the standpoints of his long poems – the masnavisMuaamalaat e Ishq and Khawab O Khayal – with his psychic disorder and love interest being the vantage point. Personality-centric criticism is fraught with misunderstandings and is hardly attuned to the modern literary canon, but Professor Narang’s insightful reading has made these sort of references quite fascinating. His interpretation, always academically rigourous, provides a detailed assessment of Mir and deflates many myths about him. Certainly, he was a poet of the oral tradition and was fully alive to the inner aesthetic of the word. However, most earlier evaluations of his work, barring some exceptions, were clichéd.

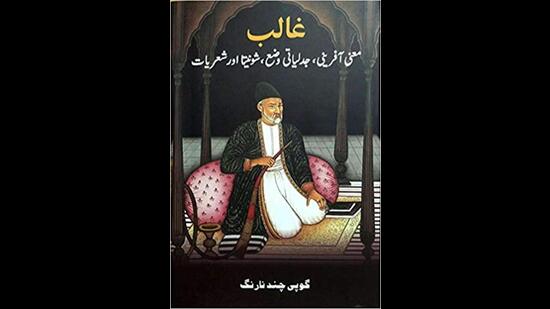

Similarly, there is no dearth of commentary on the much-admired Mirza Asad Ullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869), but Gopi Chand Narang intriguingly locates his creative genius in a world of banality 250 years ago. His trail-blazing book Ghalib: His Thought, Dialectical Poetics & the Indian Mind tries to understand the poet’s world view in the context of the ongoing debate that truth is not an absolute concept and that it is what we construct through language to fulfil our cultural needs. Narang asserts that Ghalib was the first Urdu poet to make us realize that the world we live in is essentially incongruous and it is where otherness shapes everything. Hence it is unreal. Curiously, this is something that postmodernism has been harping on for decades. Ghalib turns his attention to hypocrisy and the inherent contradictions in our social mores, which impels him to upturn all norms of social behaviour and faith.

Professor Narang attempts to collate the heterogenous poetic traditions in which Ghalib’s poetry is located. Mapping the complex terrain of his poetry, he explains his widely quoted couplets to show that they reveal a state of “no mind”, which closely resembles the Buddhist philosophy of Sunyata. Highlighting the contours of Sunyata, he says it is not a religious or metaphysical concept; nor is it a means of meditation. It is a way of thinking that upends every ideology, belief, and social practice and enables the individual to go beyond the apparent to see its otherness. This, then, is what runs through Ghalib’s poetry.

The critical evaluation of fiction has not taken firm root in Urdu. Here again, Narang tried to supplement what has been lacking. His Fiction Sheriyaat: Tashkeel o Tanqeed (Poetics of Fiction: Formation and Criticism) discusses how fiction readjusts innate human impulses. A discerning textual study of Manto, Prem Chand, Rajender Singh Bedi, Intizar Husain, Balwant Singh, Sajid Rasheed, Anjum Usmani and Gulzar makes it clear that ideology, philosophy, history, aesthetic and linguistics constitute the cultural space from which fiction draws its breath.

Narang deconstructs the well-known stories of Prem Chand, Bedi, and Manto. Subjecting Prem Chand’s story Kafan(The Shroud) to a close reading, he asserts that the shroud of the title does not refer to the cloth that covers the body of Budhyia but to her womb which covered her unborn child.

Narang’s departure has caused a pall of gloom to descend on the subcontinent’s Urdu literary horizon. It calls to mind Ram Narian Mauzoo’s lines:

Majnu jo mar gya hai to jangal udas hai.

Shafey Kidwai is a bilingual critic and author and is a professor of Mass communication at the Alkigarh Muslim University

The views expressed are personal

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Urdu literary theorist Gopi Chand Narang (born in 1931), who was honoured by both India and Pakistan, died on June 15. His scholarship pegs down two hostile nations, each of which conferred its highest honour on him – he was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 2004 and the Sitar e-Imtiaz in 2012.

Professor Narang wrote more than 70 books in Urdu, English and Hindi. Academic rigour and a profound interest in new criticism, stylistics, semiotics and sociolinguistics run through his work. In a literary journey spread over more than seven decades, he meticulously spelt out a well-defined literary poetics that helped Urdu criticism extricate itself from the bond of theme-centred evaluation.

On the right side of many significant literary trends, his writing reveals his sharp critical insight. He engaged perceptively with different ideological positions without a trace of a totalitarian authorial discourse. He deftly applied Arabic-Persian literary theories, Sanskrit poetics, structuralism and post-structuralism to every genre from the ghazal to fiction. Sakhtiyaat, Pas Sakhtiyat aur Mashriqi Sheriyaat (Structuralism, Post-structuralism and Eastern poetics, 1993), an example of his profound scholarship, gives equal attention to western and eastern poetics. Divided into three sections, the book looks at the concept of language and literature and the construction of reality. It shows how structuralism strikes at the roots of the metaphysical concept of reality. The certitude of literature that mirrors reality owes much to common sense and historicity. Professor Narang judiciously connects Ferdinand de Saussure’s sound pattern of words and psychological phenomena with Prakrta Dhvani (the psychological) and Vaikarta Dhvani (the physical). He also drew parallels between Saussure’s views that language has no positive value except in opposition to something else with the Apoha theory of Buddhist logicians for whom the meaning of a word lies not in its positivity but in the contradistinction of its correlates. Having yoked eastern poetics with structuralism and post-structuralism, he spells out the contours of the new model of criticism. The debate also explores the simultaneous quest for a universal and national identity.

Read more: Interview with Gopi Chand Narang

Professor Narang also deftly used deconstructionism to re-evaluate the whole range of Urdu poetry, including the work of Mir, Ghalib, Iqbal, Faiz, Firaq, Shahryar and Mohammad Alvi, among others.

Mir Taqi Mir’s (1723-1810) nuanced and multisensory poetry is usually read through the prism of his personal life that was mired in deprivation. Less rigorous critics have used terms to do with agony, angst, the deep sense of loss, longing, and the pangs of unrequited love to evaluate Mir’s lucent opus. This has resulted in him being erroneous labelled as a poet of simplicity and emotional flourishes. Always piqued by the cliché ridden critical idiom, Professor Narang’s latest book, The Hidden Garden: Mir Taqi Mir (Penguin Random House, 2021), unravels the various layers of the poet’s “deceptive simplicity”. He seeks to locate Mir in our current epoch of untruth through a close reading of his ghazals. “Mir is not a simple poet by any means. I have tried to unwrap every hidden pathway, every dark trail that zigzags, every footprint that shows something new, and every trajectory that leads to a more hopeful future. Mir is not a poet of unrequited love; his voice reveals and recreates echoes of the medieval age’s soul-searching and the transcendental thought of the bhakti tradition and spirituality that runs parallel to the self-consuming mystic narrative of Mansur and Majnu.”

Review: The Hidden Garden – Mir Taqi Mir by Gopi Chand Narang

Mir’s various phases are studied from the standpoints of his long poems – the masnavisMuaamalaat e Ishq and Khawab O Khayal – with his psychic disorder and love interest being the vantage point. Personality-centric criticism is fraught with misunderstandings and is hardly attuned to the modern literary canon, but Professor Narang’s insightful reading has made these sort of references quite fascinating. His interpretation, always academically rigourous, provides a detailed assessment of Mir and deflates many myths about him. Certainly, he was a poet of the oral tradition and was fully alive to the inner aesthetic of the word. However, most earlier evaluations of his work, barring some exceptions, were clichéd.

Similarly, there is no dearth of commentary on the much-admired Mirza Asad Ullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869), but Gopi Chand Narang intriguingly locates his creative genius in a world of banality 250 years ago. His trail-blazing book Ghalib: His Thought, Dialectical Poetics & the Indian Mind tries to understand the poet’s world view in the context of the ongoing debate that truth is not an absolute concept and that it is what we construct through language to fulfil our cultural needs. Narang asserts that Ghalib was the first Urdu poet to make us realize that the world we live in is essentially incongruous and it is where otherness shapes everything. Hence it is unreal. Curiously, this is something that postmodernism has been harping on for decades. Ghalib turns his attention to hypocrisy and the inherent contradictions in our social mores, which impels him to upturn all norms of social behaviour and faith.

Professor Narang attempts to collate the heterogenous poetic traditions in which Ghalib’s poetry is located. Mapping the complex terrain of his poetry, he explains his widely quoted couplets to show that they reveal a state of “no mind”, which closely resembles the Buddhist philosophy of Sunyata. Highlighting the contours of Sunyata, he says it is not a religious or metaphysical concept; nor is it a means of meditation. It is a way of thinking that upends every ideology, belief, and social practice and enables the individual to go beyond the apparent to see its otherness. This, then, is what runs through Ghalib’s poetry.

The critical evaluation of fiction has not taken firm root in Urdu. Here again, Narang tried to supplement what has been lacking. His Fiction Sheriyaat: Tashkeel o Tanqeed (Poetics of Fiction: Formation and Criticism) discusses how fiction readjusts innate human impulses. A discerning textual study of Manto, Prem Chand, Rajender Singh Bedi, Intizar Husain, Balwant Singh, Sajid Rasheed, Anjum Usmani and Gulzar makes it clear that ideology, philosophy, history, aesthetic and linguistics constitute the cultural space from which fiction draws its breath.

Narang deconstructs the well-known stories of Prem Chand, Bedi, and Manto. Subjecting Prem Chand’s story Kafan(The Shroud) to a close reading, he asserts that the shroud of the title does not refer to the cloth that covers the body of Budhyia but to her womb which covered her unborn child.

Narang’s departure has caused a pall of gloom to descend on the subcontinent’s Urdu literary horizon. It calls to mind Ram Narian Mauzoo’s lines:

Majnu jo mar gya hai to jangal udas hai.

Shafey Kidwai is a bilingual critic and author and is a professor of Mass communication at the Alkigarh Muslim University

The views expressed are personal

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading