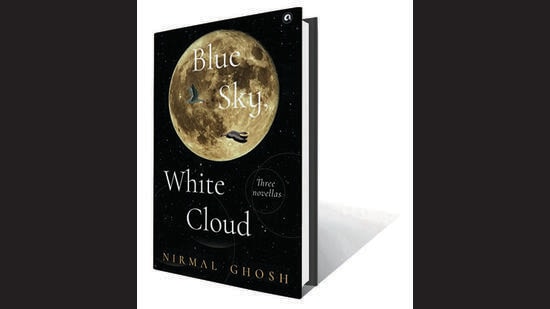

Review: Blue Sky White Cloud by Nirmal Ghosh

In The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh discusses how contemporary literary fiction has failed to address climate change: “When I try to think of writers whose imaginative work has communicated a more specific sense of the accelerating changes in our environment, I find myself at a loss; of literary novelists writing in English only a handful of names come to mind… The literary mainstream, even as it has become more engagé on many fronts, remains just as unaware of the crisis on our doorstep as the population at large.”

In light of this analysis, journalist and wildlife conservationist Nirmal Ghosh’s Blue Sky, White Cloud, a collection of three novellas, seems like a promising attempt to engage with humanity’s impact on the environment. His stories foreground animals in the narrative instead of donning the usual anthropocentric lens. These creatures do not live in a pristine Eden. Human footprints are writ large on their homes and have upset the life they or their forbears were accustomed to. Human-animal conflict is omnipresent, with disastrous consequences.

Arati Kumar-Rao’s black-and-white illustrations are delightful companions to the stories. Her renderings of landscapes and animals are often more evocative than the words on the page. My only grouse is that most are tiny — some span a third of a page where they deserve a spread.

River Storm, the first novella, features a male elephant born in the grasslands along the Brahmaputra. We are privy to his life experiences: his first unpleasant interaction with humans as a three-year-old, friendship with an older bull elephant, and perplexity on witnessing roads, logging, and tea gardens fragment the forest in which he earlier gallivanted freely. His life is closely interlinked with Deben’s, who is roughly the same age as the elephant and knows the forest well.

The story seeks to nurture sympathy for animals in a homocentric world, but fails. The descriptions of the landscape and the elephant’s activities are prosaic, more like an environmental science textbook rather than a novella. The conflicts that animate fictional narratives are absent or dreary.

Although the elephant is ostensibly at the centre of the story, his characterisation is flat. He seems to have few other facets beyond suffering from and reacting to human depredations. There is no character arc either to sustain interest. The two humans in the story, Deben and Ronesh, grapple with dilemmas, but the author does not delve into these in a sustained manner. Thus, the mostly linear narrative ends up with a predictable ending too.

Spirit of the Hills, the second story, is a replica of the first, with some variations. A female leopard replaces the elephant; Hira Singh, a forest guard, is the conflicted human instead of Deben; and the setting shifts to Uttarakhand. But the plot remains the same, resulting in an identical denouement.

However, it has more layers than the former. Hira Singh’s character is more fleshed out, though the leopard is as unidimensional as the elephant. Specific details about the other humans in the story — a group that poached and cooked deer, a wife-beating royal vacationing in a forest rest house — make its fictional universe more intriguing.

This story also gives a better sense of the landscape. The author describes how chaurs or grasslands in the valley remain cool even on summer afternoons. We learn about an incongruous bougainvillea that was once a decorative plant in someone’s yard — a relic of a village that had been relocated to establish a national park. The forest department had left it undisturbed as it did not proliferate like the invasive lantana bushes. Ghanta Devi, a hilltop shrine attracting ascetics and seekers, is a recurring location that anchors the plot.

The third novella, Blue Sky, White Cloud, is a refreshing departure from the other two. It eschews their simplistic plotting to present a rich tapestry of events, characters, and locations. Wildlife biologist Nadia travels to Mongolia for her research on geese that migrate to India over the winter. With the help of her Mongolian guide Bayar, she tags a pair of bar-headed geese, BH6 and BH7. At a conference in Stockholm, she meets Vivek, a former journalist now in a powerful position. Their and the goose pair’s trajectories intertwine at a high-altitude Himalayan wetland. Unexpected events and connections build dramatic tension, making for an engaging read.

Although the story seems to shift focus from animals to humans, it is the most effective at portraying the magnitude and ramifications of current ecological crises. The narrative traversing various landscapes and countries helps draw links between random entities such as electric wires around Bharatpur, an upcoming dam in the Himalayas, and the Qinghai Lake in Tibet. It conveys how decisions made in one part of the globe can wreak havoc thousands of miles away.

Making these connections is challenging not only for fiction, but also for scientists seeking to link specific extreme-weather events to climate change (albeit for different reasons). Blue Sky, White Cloud is an intrepid attempt to convey the Anthropocene’s impact on the world and its inhabitants. And although it falters, it opens a door to how fiction can address the environmental crisis and climate catastrophe.

Syed Saad Ahmed is a writer and communications professional.

In The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh discusses how contemporary literary fiction has failed to address climate change: “When I try to think of writers whose imaginative work has communicated a more specific sense of the accelerating changes in our environment, I find myself at a loss; of literary novelists writing in English only a handful of names come to mind… The literary mainstream, even as it has become more engagé on many fronts, remains just as unaware of the crisis on our doorstep as the population at large.”

In light of this analysis, journalist and wildlife conservationist Nirmal Ghosh’s Blue Sky, White Cloud, a collection of three novellas, seems like a promising attempt to engage with humanity’s impact on the environment. His stories foreground animals in the narrative instead of donning the usual anthropocentric lens. These creatures do not live in a pristine Eden. Human footprints are writ large on their homes and have upset the life they or their forbears were accustomed to. Human-animal conflict is omnipresent, with disastrous consequences.

Arati Kumar-Rao’s black-and-white illustrations are delightful companions to the stories. Her renderings of landscapes and animals are often more evocative than the words on the page. My only grouse is that most are tiny — some span a third of a page where they deserve a spread.

River Storm, the first novella, features a male elephant born in the grasslands along the Brahmaputra. We are privy to his life experiences: his first unpleasant interaction with humans as a three-year-old, friendship with an older bull elephant, and perplexity on witnessing roads, logging, and tea gardens fragment the forest in which he earlier gallivanted freely. His life is closely interlinked with Deben’s, who is roughly the same age as the elephant and knows the forest well.

The story seeks to nurture sympathy for animals in a homocentric world, but fails. The descriptions of the landscape and the elephant’s activities are prosaic, more like an environmental science textbook rather than a novella. The conflicts that animate fictional narratives are absent or dreary.

Although the elephant is ostensibly at the centre of the story, his characterisation is flat. He seems to have few other facets beyond suffering from and reacting to human depredations. There is no character arc either to sustain interest. The two humans in the story, Deben and Ronesh, grapple with dilemmas, but the author does not delve into these in a sustained manner. Thus, the mostly linear narrative ends up with a predictable ending too.

Spirit of the Hills, the second story, is a replica of the first, with some variations. A female leopard replaces the elephant; Hira Singh, a forest guard, is the conflicted human instead of Deben; and the setting shifts to Uttarakhand. But the plot remains the same, resulting in an identical denouement.

However, it has more layers than the former. Hira Singh’s character is more fleshed out, though the leopard is as unidimensional as the elephant. Specific details about the other humans in the story — a group that poached and cooked deer, a wife-beating royal vacationing in a forest rest house — make its fictional universe more intriguing.

This story also gives a better sense of the landscape. The author describes how chaurs or grasslands in the valley remain cool even on summer afternoons. We learn about an incongruous bougainvillea that was once a decorative plant in someone’s yard — a relic of a village that had been relocated to establish a national park. The forest department had left it undisturbed as it did not proliferate like the invasive lantana bushes. Ghanta Devi, a hilltop shrine attracting ascetics and seekers, is a recurring location that anchors the plot.

The third novella, Blue Sky, White Cloud, is a refreshing departure from the other two. It eschews their simplistic plotting to present a rich tapestry of events, characters, and locations. Wildlife biologist Nadia travels to Mongolia for her research on geese that migrate to India over the winter. With the help of her Mongolian guide Bayar, she tags a pair of bar-headed geese, BH6 and BH7. At a conference in Stockholm, she meets Vivek, a former journalist now in a powerful position. Their and the goose pair’s trajectories intertwine at a high-altitude Himalayan wetland. Unexpected events and connections build dramatic tension, making for an engaging read.

Although the story seems to shift focus from animals to humans, it is the most effective at portraying the magnitude and ramifications of current ecological crises. The narrative traversing various landscapes and countries helps draw links between random entities such as electric wires around Bharatpur, an upcoming dam in the Himalayas, and the Qinghai Lake in Tibet. It conveys how decisions made in one part of the globe can wreak havoc thousands of miles away.

Making these connections is challenging not only for fiction, but also for scientists seeking to link specific extreme-weather events to climate change (albeit for different reasons). Blue Sky, White Cloud is an intrepid attempt to convey the Anthropocene’s impact on the world and its inhabitants. And although it falters, it opens a door to how fiction can address the environmental crisis and climate catastrophe.

Syed Saad Ahmed is a writer and communications professional.