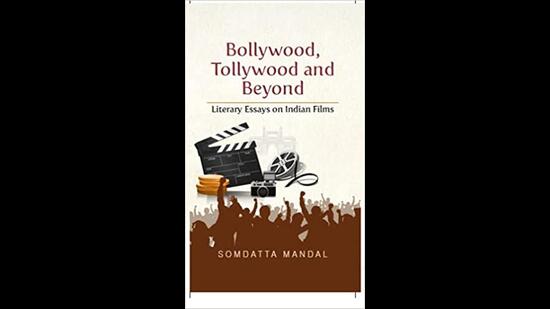

Review: Bollywood, Tollywood and Beyond – Literary Essays on Indian Films

Film studies has widened the scope of writing on film and has also broadened the readership, taking it beyond the exclusive domain of film scholars and academics who teach film theory. Pushed along by the need to express their passion for cinema, academics from different fields and non-academics too are stepping into this field of specialized writing.

Somdatta Mandal, who retired as chairperson of the department of English at Viswa Bharati, Santi Niketan, is the author of Reflections, Refractions and Rejections: Three American Writers and the Celluloid World (2002) and Film and Fiction: Word into Image (2005). Her latest work comprises 18 powerful essays that deal with three completely different segments – Thematic Studies, Eminent Personalities and Directors, and Individual Films. Indeed, this book has enough matter for three separate volumes. Though a pure academic, Mandal steers clear of heavy theory that might confound general readers and her language and style are free of jargon.

Her socio-historical approach to cinema touches on such subjects as films on the Partition and its impact both in Punjab and Bengal, and on the representation of minority communities such as Anglo-Indians and Muslims. While this book provides a powerful frame of reference for students and scholars of film studies in these areas, it is a bit surprising that the author has left out Shyam Benegal’s three Muslim-centric films – Mammo (1994), Sardari Begum (1996) and Zubeida.

Interestingly, the book features both widely known films that the reader might have watched multiple times and a few that are lesser known too and includes discussions and analyses that stray intentionally into sociological issues that shed light and also raise questions. Among these one may mention her analysis and study into films like Deepa Mehta’s Earth 1947 based on Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel The Ice Candy Man, and a very detailed analysis of Eisha Marjara’s little known film Desperately Seeking Helen in the chapter Aping the Vamp & Identity Issues in the Diaspora.

Mandal’s analysis of “Partition” films is very insightful. The event has become something of a two-edged sword for filmmakers, who often look at it through cinematic lenses and personal perspectives. This section is divided into four detailed chapters. The first, Dismemberment and/or Reconstitution: Visual Representation of the Partition of Bengal is the most significant as most Indians link Partition with Punjab and Bengal is hardly discussed. The second, Reliving the Bengal Partition in Documentaries includes a detailed study of Supriyo Sen’s two-part reminiscences about the Partition as seen through his own parents in the films Way Back Home and Imaginary Homeland. The third section, Celluloid Representations of the Partition of Punjab, scans films like Tamas, ML Anand’s Lahore (1949), considered to be one of the earliest attempts to depict the Partition of India on celluloid, and Kartar Singh (1959) directed by Saifuddin Saif, which the author states “is considered to be one of the all-time great Punjabi films to ever come out of Pakistan.”

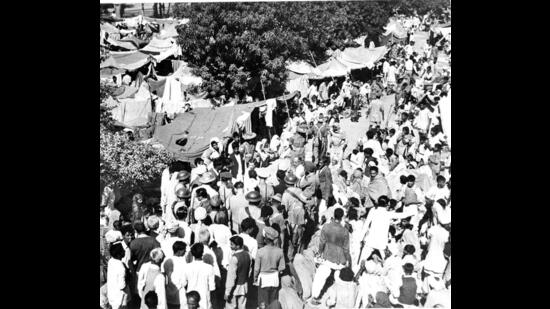

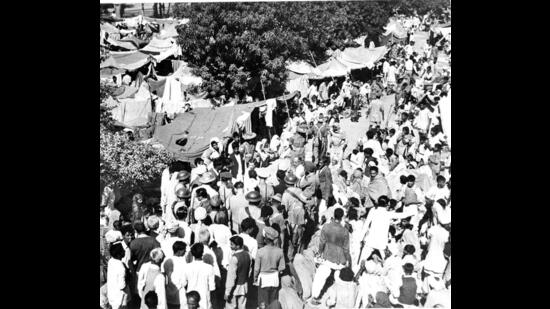

Among mainstream Indian films, surprisingly the author mentions Manmohan Desai’s Chhalia (1960) which deals with the director’s favourite lost-and-found formula but with the action placed on the eve of Partition. And who can ever forget MS Sathyu’s classic Garm Hawa based on Ismat Chughtai’s story? The section entitled Films on the Partition, Border-Crossings and Survival, discusses classic films like Nemai Ghosh’s Chinnamul (1951) shot almost entirely on location in the Sealdah Station in Calcutta filled with real refugees waiting – for what, they have no idea. Interestingly, a small role was played by a young man who approached Ghosh for work in his film. His name is Ritwik Ghatak.

Other than the Ghatak trilogy based on the impact of Partition among families and the youth of Bengal, the author also takes a close look at some Bengali films made in the 1970s. Among them are Bimal Basu’s Nabarag (1971) starring Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen, Rajen Tarafdar’s Palanka (1976), and the first Bangladeshi production, Surya Dighal Bari (1976), jointly directed by Masiruddin Shaker and Sheikh Niamat Ali.

In Women in Cinematic Representation, Mandal walks us through cinematic adaptations of Tagore’s stories and novels. Though questions like “Was Tagore a Feminist?” have been explored and analysed to death, they do highlight Mandal’s personal interpretation of women characters from Teen Kanya through Charulata to GhareBaire.

An enlightening chapter, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons! analyses Barrenness vs Motherhood in Bengali Cinema with a focus on Rabindranath Tagore’s childless women in his creative work and also within the Tagore family. This is a subject that few have dared to touch. Within the Tagore family, Debendranath Tagore’s son Jyotirindranath and grandson Balendranath (son of Birendranath) had no children. Three of Tagore’s children’s marriages were childless and his only son Rathindranath too did not have children. Mandal also looks at childless women in Satyajit Ray’s films (Monihara, Devi, Charulata and GhareBaire) along with some women in Rituparna Ghosh’s films like Khela and Antarmahal.

The book has a concisely worded foreword by noted film theorist, critic and scholar MK Raghavendra and a detailed introduction by the author herself. While the cover is attractive, the photographic reproductions of stills from films lack clarity as they are printed within the textual matter and not on separately printed and bound art paper.

In sum, this is a book rich in insights that will appeal to both the film scholar and to the intelligent general reader.

Shoma A Chatterji is an independent journalist. She lives in Kolkata

The views expressed are personal

This winter season, get Flat 20% Off on Annual Subscription Plans

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium

Film studies has widened the scope of writing on film and has also broadened the readership, taking it beyond the exclusive domain of film scholars and academics who teach film theory. Pushed along by the need to express their passion for cinema, academics from different fields and non-academics too are stepping into this field of specialized writing.

Somdatta Mandal, who retired as chairperson of the department of English at Viswa Bharati, Santi Niketan, is the author of Reflections, Refractions and Rejections: Three American Writers and the Celluloid World (2002) and Film and Fiction: Word into Image (2005). Her latest work comprises 18 powerful essays that deal with three completely different segments – Thematic Studies, Eminent Personalities and Directors, and Individual Films. Indeed, this book has enough matter for three separate volumes. Though a pure academic, Mandal steers clear of heavy theory that might confound general readers and her language and style are free of jargon.

Her socio-historical approach to cinema touches on such subjects as films on the Partition and its impact both in Punjab and Bengal, and on the representation of minority communities such as Anglo-Indians and Muslims. While this book provides a powerful frame of reference for students and scholars of film studies in these areas, it is a bit surprising that the author has left out Shyam Benegal’s three Muslim-centric films – Mammo (1994), Sardari Begum (1996) and Zubeida.

Interestingly, the book features both widely known films that the reader might have watched multiple times and a few that are lesser known too and includes discussions and analyses that stray intentionally into sociological issues that shed light and also raise questions. Among these one may mention her analysis and study into films like Deepa Mehta’s Earth 1947 based on Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel The Ice Candy Man, and a very detailed analysis of Eisha Marjara’s little known film Desperately Seeking Helen in the chapter Aping the Vamp & Identity Issues in the Diaspora.

Mandal’s analysis of “Partition” films is very insightful. The event has become something of a two-edged sword for filmmakers, who often look at it through cinematic lenses and personal perspectives. This section is divided into four detailed chapters. The first, Dismemberment and/or Reconstitution: Visual Representation of the Partition of Bengal is the most significant as most Indians link Partition with Punjab and Bengal is hardly discussed. The second, Reliving the Bengal Partition in Documentaries includes a detailed study of Supriyo Sen’s two-part reminiscences about the Partition as seen through his own parents in the films Way Back Home and Imaginary Homeland. The third section, Celluloid Representations of the Partition of Punjab, scans films like Tamas, ML Anand’s Lahore (1949), considered to be one of the earliest attempts to depict the Partition of India on celluloid, and Kartar Singh (1959) directed by Saifuddin Saif, which the author states “is considered to be one of the all-time great Punjabi films to ever come out of Pakistan.”

Among mainstream Indian films, surprisingly the author mentions Manmohan Desai’s Chhalia (1960) which deals with the director’s favourite lost-and-found formula but with the action placed on the eve of Partition. And who can ever forget MS Sathyu’s classic Garm Hawa based on Ismat Chughtai’s story? The section entitled Films on the Partition, Border-Crossings and Survival, discusses classic films like Nemai Ghosh’s Chinnamul (1951) shot almost entirely on location in the Sealdah Station in Calcutta filled with real refugees waiting – for what, they have no idea. Interestingly, a small role was played by a young man who approached Ghosh for work in his film. His name is Ritwik Ghatak.

Other than the Ghatak trilogy based on the impact of Partition among families and the youth of Bengal, the author also takes a close look at some Bengali films made in the 1970s. Among them are Bimal Basu’s Nabarag (1971) starring Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen, Rajen Tarafdar’s Palanka (1976), and the first Bangladeshi production, Surya Dighal Bari (1976), jointly directed by Masiruddin Shaker and Sheikh Niamat Ali.

In Women in Cinematic Representation, Mandal walks us through cinematic adaptations of Tagore’s stories and novels. Though questions like “Was Tagore a Feminist?” have been explored and analysed to death, they do highlight Mandal’s personal interpretation of women characters from Teen Kanya through Charulata to GhareBaire.

An enlightening chapter, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons! analyses Barrenness vs Motherhood in Bengali Cinema with a focus on Rabindranath Tagore’s childless women in his creative work and also within the Tagore family. This is a subject that few have dared to touch. Within the Tagore family, Debendranath Tagore’s son Jyotirindranath and grandson Balendranath (son of Birendranath) had no children. Three of Tagore’s children’s marriages were childless and his only son Rathindranath too did not have children. Mandal also looks at childless women in Satyajit Ray’s films (Monihara, Devi, Charulata and GhareBaire) along with some women in Rituparna Ghosh’s films like Khela and Antarmahal.

The book has a concisely worded foreword by noted film theorist, critic and scholar MK Raghavendra and a detailed introduction by the author herself. While the cover is attractive, the photographic reproductions of stills from films lack clarity as they are printed within the textual matter and not on separately printed and bound art paper.

In sum, this is a book rich in insights that will appeal to both the film scholar and to the intelligent general reader.

Shoma A Chatterji is an independent journalist. She lives in Kolkata

The views expressed are personal

This winter season, get Flat 20% Off on Annual Subscription Plans

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium