Review: Dare to Learn edited by the Malala Fund

When 17-year-old Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014, she gave an outstanding speech. She said, “This award is not just for me. It is for those forgotten children who want education. It is for those frightened children who want peace. It is for those voiceless children who want change.” It was only fitting, therefore, that Yousafzai shared the prestigious prize with Indian activist Kailash Satyarthi. What they had in common was their fight for children’s right to education.

While critics of Yousafzai continue to view her as a celebrity propped up by the West who has not done anything of significance to deserve the honour, some of us remember that this courageous girl was shot by the Taliban for claiming her right to go to school and learn in an environment free of fear. Her outspoken attitude and, more so, her gender, made her a target.

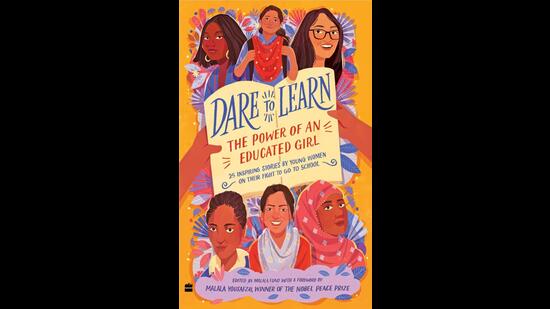

Dare to Learn: The Power of an Educated Girl, published by HarperCollins India, is a moving collection of 25 personal essays written by young women from various parts of the world. They draw inspiration from Yousafzai and, in turn, inspire Yousafzai to carry on with her work. These essays were originally written for the Malala Fund’s digital publication Assembly – a space for creative expression, exchange of ideas, solidarity and sisterhood. The book has been edited by a team led by Tess Thomas. Yousafzai has written the foreword.

“In every community, and in every country, girls are already speaking out. They are challenging injustice, confronting gender discrimination, and overcoming obstacles to go to school,” writes Yousafzai. “These girls do not need my advice on how to fight for their rights because they are already fighting. What I can do is to help amplify their voices,” she adds.

The anthology features essays written by young women from India, Pakistan, Canada, Iraq, Nigeria, Syria, Turkey, Uganda, Venezuela, Ethiopia, the United States of America, Brazil, the Morocco, and the United Kingdom. Nine of the essays are by Indians, and this is not a matter of pride. If you are wondering why, Yousafzai explains, “Many of the girls in this book are from India, where nearly 40 per cent of girls from ages 15 to 18 are out of school.”

The essays delve into the structural reasons that keep them from accessing education. Manisha Bharti – “a Dalit girl growing up in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh” – writes about facing caste discrimination from non-Dalits, and gender discrimination from people within her own community. Mungli Hasda hails from the Bodoland Territorial Region, Assam, and belongs to one of many families that “had to leave their villages due to violent conflicts between armed insurgent groups or environmental degradation such as floods and droughts.”

Anoyara Khatun, who lives in a village in North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, had become a victim of human trafficking after her father died. She was rescued from the family holding her captive in Delhi, and brought to her village so that she could resume her education. Shweta Sharma, who is “from an area near the Jaipur railway station” in Rajasthan, had her education interrupted because of “terrible fights” between her parents. Things worsened to such an extent that her mother had to leave the house, and she had to accompany her mother. Home schooling could not make up for the absence from school; teachers were not supportive.

READ MORE: Excerpt: Dare To Learn: The Power of An Educated Girl

This book emphasizes that barriers to girls’ education exist everywhere but there are critical differences in the nature of those obstacles. Those who venture into activism are deeply aware of the particularities of their context, and they devise solutions that make sense locally. They refuse to let themselves be defined by their trauma but they carry the memory of that suffering and use it as fuel to write a narrative of hope for themselves and their communities.

Aisha Mustapha from Nigeria, who escaped an attack by Boko Haram, wants to study further and become a nurse so that she can support women in her community. This beautiful dream was born in a horrific moment when she saw a pregnant women die in the process of childbirth. The baby was hurriedly delivered during a Boko Haram attack, and the mother could not survive due to lack of appropriate medical attention needed at the right time. The aspiration to become a nurse is also rooted in the desire to pay it forward. Mustapha is alive today because a stranger became her foster mother when she was running from Boko Haram.

Azka Athar grew up in Pakistan, where “it is not a common practice for parents to send their daughters abroad alone for higher education right after high school”. She was interested in pursuing stem cell research, so she began applying to colleges outside her own country. She got accepted into a foreign university with a full scholarship but she cancelled her plans. She felt her plans “were not worth the pain” that she would cause her parents by going abroad. She took a gap year, studied industrial design at a local university, and became the leader of an all-female team representing Pakistan at an international student engineering competition in the UK, where participants had to “design, build, test and race a formula-style racing car”.

Rahel Sheferaw, who was born in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, lives in a rural area with little access to education. She writes, “Child marriage is deep rooted in our community, so after girls complete their primary education, oftentimes their families don’t allow them to continue with their secondary education.” When community elders started pushing her to get married, she complained to the school administration. They got a local organization involved, which engaged in dialogue with religious leaders and the local administration to stall the wedding. Now Sheferaw works with the same organization to run a girls’ club at her school.

What does this club do? Girls who join it are taught how to negotiate with family members and community elders who pressurize them into child marriage. They also learn about sexual health and reproductive education. Sheferaw writes, “In my community, there’s not a lot of knowledge about sanitary napkins or even underwear and why girls should use them. During their menstruation, girls often don’t go to school because they can’t manage the bleeding.” By providing such education, the club is trying to minimize the number of female drop-outs.

This book will be an eye-opener for people who are under the impression that there is a level-playing field. The denial of opportunities to young women who are eager to learn is so widespread that one wonders how long it will take to set things right. However, the most important takeaway from this book is that they are not waiting for anyone. They are leading.

Tabitha Willis from the United States writes about her experiences as a Black girl interested in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) disciplines. She was routinely labelled by school teachers as “a problem child” because of her “speech and hearing complications coupled with learning difficulties”. They also used racist slurs against her.

She was able to navigate the discrimination thanks to her determination, “the unwavering support of her father” and two amazing teachers who recognized her potential and passion. She interviewed for a position with a natural history museum in Chicago. This gave her an opportunity to teach “groups of younger kids about science”. She loved seeing their eyes light up because her job description involved getting them to think of science as “actually cool”. Her mission is “to make it easier for the next generation of Black students in Chicago to study STEM”, so she is working with institutions to make them examine closely “the barriers preventing students of colour from participating in these opportunities”. This includes multiple issues, such as lack of awareness, transport-related concerns, and funding support.

The essays take us into the inner worlds of the 25 contributors to this anthology. Katiuska Sanchez writes about finding solace in The Diary of Anne Frank during the economic and humanitarian crises in Venezuela in 2014. Her mother forbade her from going to school as it was unsafe for a young woman to be out on the streets alone. Many of the protestors, whose human rights were violated by the police and military, were between 18 and 26 years of age.

She writes, “That book inspired me to believe that everything I felt was okay, that being scared was okay, that not knowing how to deal with the stress was okay, that feeling anxiety wasn’t wrong and that, in fact, I could find ways to deal with my anxiety and make it my friend.” She too started writing a diary. Jotting down her thoughts provided some relief.

She moved to Panama, came back to Venezuela, migrated to Peru, and is now in Chile. The cultural differences, the emotional instability, and the time spent away from loved ones, has been tough on her but she believes that these experiences will help her grow as a person. She wants to study at a university, learn different languages, work as a teacher, and write a lot.

Charitie Ropati, a Samoan indigenous woman from Alaska, is concerned about the fact that Native American students “don’t see themselves in the curriculum that they learn, on a land that was once theirs”, so they have little motivation to complete their schooling. She began researching graduation rates and drop-out percentages when she was 16 years old, and ended up creating a curriculum that “highlights the atrocities faced by my ancestors and focuses on an Indigenous perspective through readings, videos and movies”. She incorporated visits by guest speakers to talk about persecution, relocation, broken treaties, and missionary activity.

She writes, “Despite everything we’ve faced, we still dance, we sing, we laugh, we smile. We still learn our traditions and go hunting. We were never meant to survive because of colonialism. But we did. We’re here. We’re here and we’re thriving. That in itself is so powerful.” These words truly capture the buoyant feeling this book hopes to leave you with.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, writer and educator who tweets @chintanwriting

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

When 17-year-old Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014, she gave an outstanding speech. She said, “This award is not just for me. It is for those forgotten children who want education. It is for those frightened children who want peace. It is for those voiceless children who want change.” It was only fitting, therefore, that Yousafzai shared the prestigious prize with Indian activist Kailash Satyarthi. What they had in common was their fight for children’s right to education.

While critics of Yousafzai continue to view her as a celebrity propped up by the West who has not done anything of significance to deserve the honour, some of us remember that this courageous girl was shot by the Taliban for claiming her right to go to school and learn in an environment free of fear. Her outspoken attitude and, more so, her gender, made her a target.

Dare to Learn: The Power of an Educated Girl, published by HarperCollins India, is a moving collection of 25 personal essays written by young women from various parts of the world. They draw inspiration from Yousafzai and, in turn, inspire Yousafzai to carry on with her work. These essays were originally written for the Malala Fund’s digital publication Assembly – a space for creative expression, exchange of ideas, solidarity and sisterhood. The book has been edited by a team led by Tess Thomas. Yousafzai has written the foreword.

“In every community, and in every country, girls are already speaking out. They are challenging injustice, confronting gender discrimination, and overcoming obstacles to go to school,” writes Yousafzai. “These girls do not need my advice on how to fight for their rights because they are already fighting. What I can do is to help amplify their voices,” she adds.

The anthology features essays written by young women from India, Pakistan, Canada, Iraq, Nigeria, Syria, Turkey, Uganda, Venezuela, Ethiopia, the United States of America, Brazil, the Morocco, and the United Kingdom. Nine of the essays are by Indians, and this is not a matter of pride. If you are wondering why, Yousafzai explains, “Many of the girls in this book are from India, where nearly 40 per cent of girls from ages 15 to 18 are out of school.”

The essays delve into the structural reasons that keep them from accessing education. Manisha Bharti – “a Dalit girl growing up in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh” – writes about facing caste discrimination from non-Dalits, and gender discrimination from people within her own community. Mungli Hasda hails from the Bodoland Territorial Region, Assam, and belongs to one of many families that “had to leave their villages due to violent conflicts between armed insurgent groups or environmental degradation such as floods and droughts.”

Anoyara Khatun, who lives in a village in North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, had become a victim of human trafficking after her father died. She was rescued from the family holding her captive in Delhi, and brought to her village so that she could resume her education. Shweta Sharma, who is “from an area near the Jaipur railway station” in Rajasthan, had her education interrupted because of “terrible fights” between her parents. Things worsened to such an extent that her mother had to leave the house, and she had to accompany her mother. Home schooling could not make up for the absence from school; teachers were not supportive.

READ MORE: Excerpt: Dare To Learn: The Power of An Educated Girl

This book emphasizes that barriers to girls’ education exist everywhere but there are critical differences in the nature of those obstacles. Those who venture into activism are deeply aware of the particularities of their context, and they devise solutions that make sense locally. They refuse to let themselves be defined by their trauma but they carry the memory of that suffering and use it as fuel to write a narrative of hope for themselves and their communities.

Aisha Mustapha from Nigeria, who escaped an attack by Boko Haram, wants to study further and become a nurse so that she can support women in her community. This beautiful dream was born in a horrific moment when she saw a pregnant women die in the process of childbirth. The baby was hurriedly delivered during a Boko Haram attack, and the mother could not survive due to lack of appropriate medical attention needed at the right time. The aspiration to become a nurse is also rooted in the desire to pay it forward. Mustapha is alive today because a stranger became her foster mother when she was running from Boko Haram.

Azka Athar grew up in Pakistan, where “it is not a common practice for parents to send their daughters abroad alone for higher education right after high school”. She was interested in pursuing stem cell research, so she began applying to colleges outside her own country. She got accepted into a foreign university with a full scholarship but she cancelled her plans. She felt her plans “were not worth the pain” that she would cause her parents by going abroad. She took a gap year, studied industrial design at a local university, and became the leader of an all-female team representing Pakistan at an international student engineering competition in the UK, where participants had to “design, build, test and race a formula-style racing car”.

Rahel Sheferaw, who was born in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, lives in a rural area with little access to education. She writes, “Child marriage is deep rooted in our community, so after girls complete their primary education, oftentimes their families don’t allow them to continue with their secondary education.” When community elders started pushing her to get married, she complained to the school administration. They got a local organization involved, which engaged in dialogue with religious leaders and the local administration to stall the wedding. Now Sheferaw works with the same organization to run a girls’ club at her school.

What does this club do? Girls who join it are taught how to negotiate with family members and community elders who pressurize them into child marriage. They also learn about sexual health and reproductive education. Sheferaw writes, “In my community, there’s not a lot of knowledge about sanitary napkins or even underwear and why girls should use them. During their menstruation, girls often don’t go to school because they can’t manage the bleeding.” By providing such education, the club is trying to minimize the number of female drop-outs.

This book will be an eye-opener for people who are under the impression that there is a level-playing field. The denial of opportunities to young women who are eager to learn is so widespread that one wonders how long it will take to set things right. However, the most important takeaway from this book is that they are not waiting for anyone. They are leading.

Tabitha Willis from the United States writes about her experiences as a Black girl interested in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) disciplines. She was routinely labelled by school teachers as “a problem child” because of her “speech and hearing complications coupled with learning difficulties”. They also used racist slurs against her.

She was able to navigate the discrimination thanks to her determination, “the unwavering support of her father” and two amazing teachers who recognized her potential and passion. She interviewed for a position with a natural history museum in Chicago. This gave her an opportunity to teach “groups of younger kids about science”. She loved seeing their eyes light up because her job description involved getting them to think of science as “actually cool”. Her mission is “to make it easier for the next generation of Black students in Chicago to study STEM”, so she is working with institutions to make them examine closely “the barriers preventing students of colour from participating in these opportunities”. This includes multiple issues, such as lack of awareness, transport-related concerns, and funding support.

The essays take us into the inner worlds of the 25 contributors to this anthology. Katiuska Sanchez writes about finding solace in The Diary of Anne Frank during the economic and humanitarian crises in Venezuela in 2014. Her mother forbade her from going to school as it was unsafe for a young woman to be out on the streets alone. Many of the protestors, whose human rights were violated by the police and military, were between 18 and 26 years of age.

She writes, “That book inspired me to believe that everything I felt was okay, that being scared was okay, that not knowing how to deal with the stress was okay, that feeling anxiety wasn’t wrong and that, in fact, I could find ways to deal with my anxiety and make it my friend.” She too started writing a diary. Jotting down her thoughts provided some relief.

She moved to Panama, came back to Venezuela, migrated to Peru, and is now in Chile. The cultural differences, the emotional instability, and the time spent away from loved ones, has been tough on her but she believes that these experiences will help her grow as a person. She wants to study at a university, learn different languages, work as a teacher, and write a lot.

Charitie Ropati, a Samoan indigenous woman from Alaska, is concerned about the fact that Native American students “don’t see themselves in the curriculum that they learn, on a land that was once theirs”, so they have little motivation to complete their schooling. She began researching graduation rates and drop-out percentages when she was 16 years old, and ended up creating a curriculum that “highlights the atrocities faced by my ancestors and focuses on an Indigenous perspective through readings, videos and movies”. She incorporated visits by guest speakers to talk about persecution, relocation, broken treaties, and missionary activity.

She writes, “Despite everything we’ve faced, we still dance, we sing, we laugh, we smile. We still learn our traditions and go hunting. We were never meant to survive because of colonialism. But we did. We’re here. We’re here and we’re thriving. That in itself is so powerful.” These words truly capture the buoyant feeling this book hopes to leave you with.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, writer and educator who tweets @chintanwriting

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading