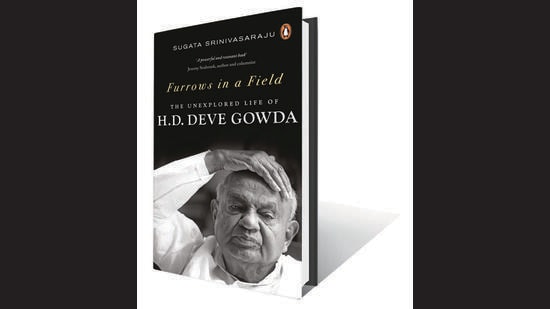

Review: Furrows in a Field; The Unexplored Life of HD Deve Gowda by Sugata Srinivasaraju

This biography of HD Deve Gowda sets out to do three things: flesh out his achievements in 11 months as PM between 1996–97; illuminate his labours as PM distilling his acumen as a state and national level politician; showcase how an ex-PM used his goodwill to raise vexatious matters besetting India within and without Parliament. To do this, it tells Gowda’s back story and emotively humanises him. In the process of investigating his subject, biographer Sugata Srinivasaraju reveals his own grasp of Karnataka politics. These three features – the subject, his back story and evolution, and the author’s command over his terrain – harmonise and propel this doorstopper of a book. Many Karnatakas and Indias are captured and refracted through Deve Gowda’s thoughts and actions, and this book achieves so much that a brief review runs the hazard of not doing any justice to it at all.

Although Srinivasaraju interviewed Gowda regularly over years and accessed his private papers, Furrows in a Field is no hagiography. This is a signal achievement considering that though the biographer has been close to his subject, he constantly questions both perceptions and facts. But why a book on the near-nonagenarian now?

Gowda, who didn’t believe in public relations, has been so misconstrued, especially given what he accomplished, that he warrants a tome. Why and how has he been understood the way he has, and what does that tell us about contemporary Kannada and Indian public discourse?

It was around 2004 that Srinivasaraju began reassessing his own perceptions about Gowda. An upper-caste-and-class-dominated public discourse had omitted a proper estimation with Gowda’s efforts over a lifetime. It exaggerated his shortcomings, his Machiavellian political savvy, his idiosyncrasies and tendency to be superstitious. This book particularly takes issue with historian Sunil Khilnani, who describes Gowda, in the famous opening pages of The Idea of India, as “the first Indian prime minister to speak neither Hindi nor English”. Wrong. His written English was functional and precise, and he spoke Hindi with a southern accent. Its longest chapter deals with the 30-year rivalry between Gowda and Ramakrishna Hegde. Kannada and Indian discourse largely sympathised with the suave upper caste Hegde and ridiculed Gowda. This book presents compelling facts and recollections that clear up misperceptions about the latter and show how wilfully wrong the media has been, and how gangrened by its own class and caste bias.

Consider what Deve Gowda did in his 11 months as PM. Estranged by caste, class and region in his own state, he identified strongly with estranged Indians away from the “mainstream”. He visited Kashmir four times, becoming the first Indian PM to visit it in years during the peak of the Kashmir movement. PV Narasimha Rao didn’t dare go between 1991 and 1996. Gowda helped the first state election to be held there post-1989. He opened dialogue with nearly every region in the North East, and created avenues for negotiating with the Naga factions. Both the Kashmiris and the people of the North East remember his efforts to this day.

He was lampooned as “fumble harmer” who nodded off at official meetings (the truth according to his biography is that his eyes may have been shut but he heard everything of note). Punjab’s farmers were so moved by his efforts to protect the farming community that they named a variety of paddy after him. His decades working in the Cauvery belt helped him master subjects that few other Indian politicians know much about: irrigation, water management and agricultural laws. Arising from a state as internally riven as Karnataka, instead of immediately placing a greater focus on his own constituency, as chief minister, he used his local knowledge to first work for the drought-prone northern parts of the state by laying the foundation of the Upper Krishna Project. It is this practical nous that he brought to the international table when he helped India and Bangladesh sign the famous Farraka Treaty, one of the more complex water-sharing treaties signed anywhere in the world. This is a rudimentary summation of his attainments. Lesser leaders receive greater and constant invocation.

At the same time, Srinivasaraju also brings up Gowda’s nepotism and quotes the man himself admitting to being unable to tackle corruption as it became enmeshed in Indian polity, and in particular in Karnataka in the 1970s. But the book also reminds the reader that the first opponents of Congress hegemony had to battle the upper-caste-and-class controls that set the terms for politics at that time. It states that HD Deve Gowda may have many failings, but individual corruption isn’t one of them. It also places the Gowda community in its proper historic setting and points out that it wasn’t economically or socially powerful a century ago. Indeed, this biography vivifies a whole social context. History has its cunning passages.

Rahul Jayaram teaches at Vidyashilp University, Bangalore.

This biography of HD Deve Gowda sets out to do three things: flesh out his achievements in 11 months as PM between 1996–97; illuminate his labours as PM distilling his acumen as a state and national level politician; showcase how an ex-PM used his goodwill to raise vexatious matters besetting India within and without Parliament. To do this, it tells Gowda’s back story and emotively humanises him. In the process of investigating his subject, biographer Sugata Srinivasaraju reveals his own grasp of Karnataka politics. These three features – the subject, his back story and evolution, and the author’s command over his terrain – harmonise and propel this doorstopper of a book. Many Karnatakas and Indias are captured and refracted through Deve Gowda’s thoughts and actions, and this book achieves so much that a brief review runs the hazard of not doing any justice to it at all.

Although Srinivasaraju interviewed Gowda regularly over years and accessed his private papers, Furrows in a Field is no hagiography. This is a signal achievement considering that though the biographer has been close to his subject, he constantly questions both perceptions and facts. But why a book on the near-nonagenarian now?

Gowda, who didn’t believe in public relations, has been so misconstrued, especially given what he accomplished, that he warrants a tome. Why and how has he been understood the way he has, and what does that tell us about contemporary Kannada and Indian public discourse?

It was around 2004 that Srinivasaraju began reassessing his own perceptions about Gowda. An upper-caste-and-class-dominated public discourse had omitted a proper estimation with Gowda’s efforts over a lifetime. It exaggerated his shortcomings, his Machiavellian political savvy, his idiosyncrasies and tendency to be superstitious. This book particularly takes issue with historian Sunil Khilnani, who describes Gowda, in the famous opening pages of The Idea of India, as “the first Indian prime minister to speak neither Hindi nor English”. Wrong. His written English was functional and precise, and he spoke Hindi with a southern accent. Its longest chapter deals with the 30-year rivalry between Gowda and Ramakrishna Hegde. Kannada and Indian discourse largely sympathised with the suave upper caste Hegde and ridiculed Gowda. This book presents compelling facts and recollections that clear up misperceptions about the latter and show how wilfully wrong the media has been, and how gangrened by its own class and caste bias.

Consider what Deve Gowda did in his 11 months as PM. Estranged by caste, class and region in his own state, he identified strongly with estranged Indians away from the “mainstream”. He visited Kashmir four times, becoming the first Indian PM to visit it in years during the peak of the Kashmir movement. PV Narasimha Rao didn’t dare go between 1991 and 1996. Gowda helped the first state election to be held there post-1989. He opened dialogue with nearly every region in the North East, and created avenues for negotiating with the Naga factions. Both the Kashmiris and the people of the North East remember his efforts to this day.

He was lampooned as “fumble harmer” who nodded off at official meetings (the truth according to his biography is that his eyes may have been shut but he heard everything of note). Punjab’s farmers were so moved by his efforts to protect the farming community that they named a variety of paddy after him. His decades working in the Cauvery belt helped him master subjects that few other Indian politicians know much about: irrigation, water management and agricultural laws. Arising from a state as internally riven as Karnataka, instead of immediately placing a greater focus on his own constituency, as chief minister, he used his local knowledge to first work for the drought-prone northern parts of the state by laying the foundation of the Upper Krishna Project. It is this practical nous that he brought to the international table when he helped India and Bangladesh sign the famous Farraka Treaty, one of the more complex water-sharing treaties signed anywhere in the world. This is a rudimentary summation of his attainments. Lesser leaders receive greater and constant invocation.

At the same time, Srinivasaraju also brings up Gowda’s nepotism and quotes the man himself admitting to being unable to tackle corruption as it became enmeshed in Indian polity, and in particular in Karnataka in the 1970s. But the book also reminds the reader that the first opponents of Congress hegemony had to battle the upper-caste-and-class controls that set the terms for politics at that time. It states that HD Deve Gowda may have many failings, but individual corruption isn’t one of them. It also places the Gowda community in its proper historic setting and points out that it wasn’t economically or socially powerful a century ago. Indeed, this biography vivifies a whole social context. History has its cunning passages.

Rahul Jayaram teaches at Vidyashilp University, Bangalore.