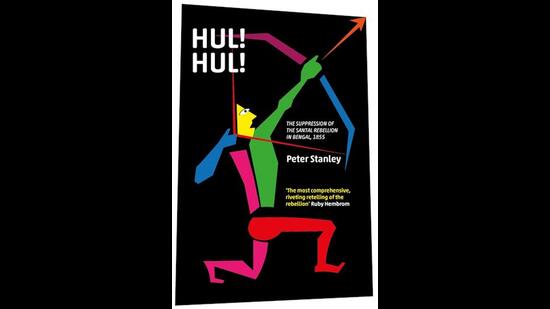

Review: Hul! Hul! by Peter Stanley

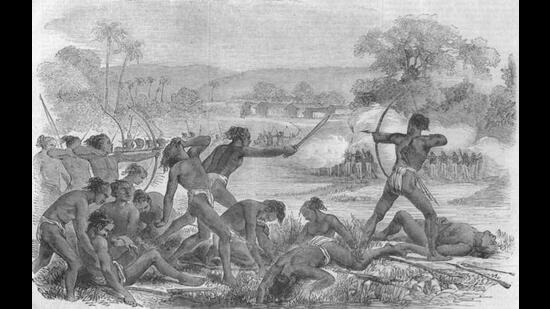

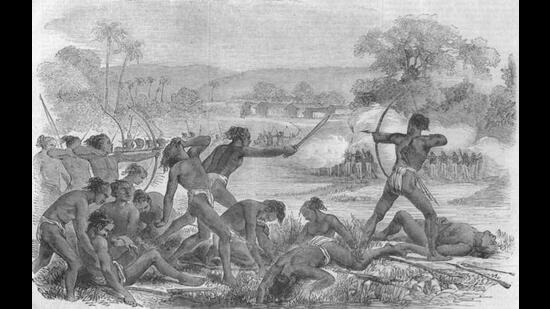

Historian Peter Stanley’s painstaking effort has shed light on the 1855 Santhal rebellion that was overshadowed by the events of the great mutiny of 1857. Perhaps the only reminders of the rebellion termed Hul, meaning the movement for liberation, are the ‘martello tower’ in Pakur and the statues of the Bhugnadihee brothers across Jharkhand. That some 10,000 Santhals were literally executed by the British has been dismissed as lost history, unworthy of any serious attention. In reality, the Hul was certainly a war with a clear cause-effect relationship. Though it lasted only six months, the lives lost would trigger many mutinies. Even after 170 years, the intangible consequences of the Hul seem discernable.

60-odd years after Robert Clive’s victory over Siraj-ud-Daula at Plassey in 1757, the British settled the Santhals in the uplands of Lower Bengal — the core of which was the Damin-i-Koh and the Rajmahal Hills, where their existence depended upon what they could harvest, hunt or gather. In less than two decades, the Santhals had transformed dense jungle into intensely farmed croplands. The British officials collected revenue while the money lenders who arrived in their wake, extorted money from the poor tribals. Dispossessed of their land, the peace-loving people recognized the cause of their oppression and acted to change their situation. Eventually, they failed against the might of the British, but not without manifesting their agency, and asserting their distinct identity. The actors and the nature of oppression may have changed, but many tribal communities continue to suffer.

A professor of history at the University of New South Wales in Canberra, Peter Stanley has written a comprehensive account of the rebellion: why it occurred, how it was fought, and how it ended. Written with empathy, the richly documented treatise provides a compelling account of the unusual collision of tribal and imperial histories, the impact of which continues to inform and define the contours of tribal existence. Had the British noticed, heeded or acted on the Santhals’ concerns regarding the dishonesty of and exploitation by the moneylenders, many might have chosen not to join the Hul. Colonial history is full of such missed opportunities, exposing the needlessness of many rebellions. By their own assessments, the enormous cost in the sufferings of the Santhals could not be justified.

History is more than the story of the victor and the vanquished. Stanley draws a vivid picture on the life and times of the Santhals, who lived in small neat villages surrounded by jungle. Each village had its sacred grove of sal trees signifying their spiritual connection with the land. Covering three seasons of the disturbed year, the book chronicles in rich detail the distorted perceptions and prejudiced assumptions about the otherwise peace-loving Santhals’ desire for justice. Despite all accounts of the rebellion having been written in English, the author has done a commendable job in presenting an exhaustive military history of the Hul.

Stanley argues that there is potential value in revisiting such insurgencies using neglected sources. Indigenous sources offer vital perspectives to the existing body of information generated by colonial authorities. They provide complementary insights into both the nature of subaltern resistance and of its suppression by the colonial masters. The book suggests that a series of studies on rebellious uprising can help better understand the roots of resistance across the subcontinent.

At a point when attempts are being made to rewrite the country’s history, nothing can be more compelling than revisiting those historical events which describe the experience of specific groups in upholding the banner of freedom and equity. More than glorifying past sacrifices, the task should be to recreate historical narratives that describe the period, and the lessons contained therein. Stanley has indeed drawn a framework for initiating a programme to undertake such studies. To that effect, Hul offers an interesting reference point.

The historical facts might appear a bit loaded in favour of military details by the colonial actors, but the author gets a glimpse of the horror of the Hul through Santhal songs and poetry which record dislocation, separation, death and grief. One such verse sums it up: “The land has gone dim / the raiders are upon us.”

Sudhirendar Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and academic.

This winter season, get Flat 20% Off on Annual Subscription Plans

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium

Historian Peter Stanley’s painstaking effort has shed light on the 1855 Santhal rebellion that was overshadowed by the events of the great mutiny of 1857. Perhaps the only reminders of the rebellion termed Hul, meaning the movement for liberation, are the ‘martello tower’ in Pakur and the statues of the Bhugnadihee brothers across Jharkhand. That some 10,000 Santhals were literally executed by the British has been dismissed as lost history, unworthy of any serious attention. In reality, the Hul was certainly a war with a clear cause-effect relationship. Though it lasted only six months, the lives lost would trigger many mutinies. Even after 170 years, the intangible consequences of the Hul seem discernable.

60-odd years after Robert Clive’s victory over Siraj-ud-Daula at Plassey in 1757, the British settled the Santhals in the uplands of Lower Bengal — the core of which was the Damin-i-Koh and the Rajmahal Hills, where their existence depended upon what they could harvest, hunt or gather. In less than two decades, the Santhals had transformed dense jungle into intensely farmed croplands. The British officials collected revenue while the money lenders who arrived in their wake, extorted money from the poor tribals. Dispossessed of their land, the peace-loving people recognized the cause of their oppression and acted to change their situation. Eventually, they failed against the might of the British, but not without manifesting their agency, and asserting their distinct identity. The actors and the nature of oppression may have changed, but many tribal communities continue to suffer.

A professor of history at the University of New South Wales in Canberra, Peter Stanley has written a comprehensive account of the rebellion: why it occurred, how it was fought, and how it ended. Written with empathy, the richly documented treatise provides a compelling account of the unusual collision of tribal and imperial histories, the impact of which continues to inform and define the contours of tribal existence. Had the British noticed, heeded or acted on the Santhals’ concerns regarding the dishonesty of and exploitation by the moneylenders, many might have chosen not to join the Hul. Colonial history is full of such missed opportunities, exposing the needlessness of many rebellions. By their own assessments, the enormous cost in the sufferings of the Santhals could not be justified.

History is more than the story of the victor and the vanquished. Stanley draws a vivid picture on the life and times of the Santhals, who lived in small neat villages surrounded by jungle. Each village had its sacred grove of sal trees signifying their spiritual connection with the land. Covering three seasons of the disturbed year, the book chronicles in rich detail the distorted perceptions and prejudiced assumptions about the otherwise peace-loving Santhals’ desire for justice. Despite all accounts of the rebellion having been written in English, the author has done a commendable job in presenting an exhaustive military history of the Hul.

Stanley argues that there is potential value in revisiting such insurgencies using neglected sources. Indigenous sources offer vital perspectives to the existing body of information generated by colonial authorities. They provide complementary insights into both the nature of subaltern resistance and of its suppression by the colonial masters. The book suggests that a series of studies on rebellious uprising can help better understand the roots of resistance across the subcontinent.

At a point when attempts are being made to rewrite the country’s history, nothing can be more compelling than revisiting those historical events which describe the experience of specific groups in upholding the banner of freedom and equity. More than glorifying past sacrifices, the task should be to recreate historical narratives that describe the period, and the lessons contained therein. Stanley has indeed drawn a framework for initiating a programme to undertake such studies. To that effect, Hul offers an interesting reference point.

The historical facts might appear a bit loaded in favour of military details by the colonial actors, but the author gets a glimpse of the horror of the Hul through Santhal songs and poetry which record dislocation, separation, death and grief. One such verse sums it up: “The land has gone dim / the raiders are upon us.”

Sudhirendar Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and academic.

This winter season, get Flat 20% Off on Annual Subscription Plans

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium