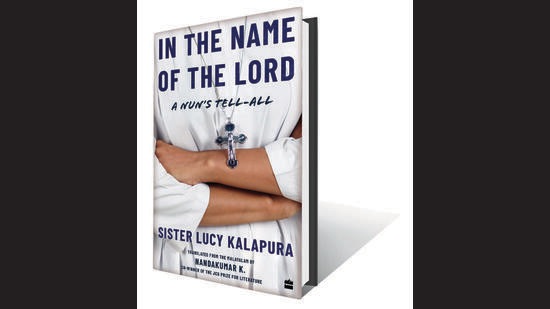

Review: In the Name of the Lord by Sister Lucy Kalapura

From the agnostic’s perspective, organised religion works by ousting logic. Discourses and gatherings are venues for brainwashing believers into acting in accordance with the ultimate Truth, as defined by the concerned religious authority. The fear of God then becomes a way to tame thousands of the faithful who are only too willing to offer their labour and their hard-earned money to strengthen the religious establishment.

It is true that most religious bodies begin with noble intentions and, even in their darkest hour, offer respite to the distraught and the restless. Often, however, humanity’s malign side takes over — dominating and superseding the more benign aspects.

This trajectory is revealed in former nun Sister Lucy Kalapura’s book In the Name of the Lord about her experience with the Catholic Church. Her distrust in the clergy began in secondary school after she saw a priest touching a classmate inappropriately. Her intention to report the incident was stymied by her mother who insisted that she stay silent. Kalapura later learnt that her sister too had gone through the same humiliation. Still, as a young girl, Kalapura didn’t demand much from life except to be allowed to live in the company of Jesus. Going against the wishes of her Chachan (father) and Kunjaanja (elder brother), she followed in the footsteps of her elder sister and became a nun. It should have been a glorious initiation into the religious life but a succession of priests, Mother Superiors, and nuns jealous of every threat to their positions poisoned her pursuit of peace and transformed her world into a sickening hell.

Kalapura describes four incidents when she was caught off-guard by white-bearded priests who tried to get physically intimate with her. While predatory incidents like these seem rampant, the author states that nuns too, at times, initiate physical relationships spurred by sexual desire or the ambition to accrue power within the church hierarchy. Repressed homosexuality is common place as illustrated by the nun from Thalassery who persistently attempted to entice Sister Kalapura into her room, and the gay priest who confined and raped another. Kalapura believes relaxing the rules around chastity would be beneficial and stresses that personal choice must prevail in these decisions.

While these revelations might leave the reader aghast, what really sets this book apart is its central revelation about how the Church controls nuns’ access to money, behaving like a strict parent whose permission needs to be sought at every step and before every petty task.

Despite teaching in Catholic schools spread across the country, Kalapura only had some meagre money of her own. As with most nuns, she had to depend on the Church for basic needs including for a supply of undergarments and sanitary pads. The nuns were forced to use white rolls of cloth or pads with poor absorption qualities. Even after an emergency allowance was provided, nuns had to beg the Mother Superior to allow them to use pads. “We had to plead for undergarments. Undergarments from close-down sales of resellers or warehouse sales of manufacturers were collected in the Provincial House… The only option was to pick what was available, whether it fitted or not,” she says.

Worse, when Kalapura was working as a principal of a primary school in Bundi, near Kota, Rajasthan, and her father suddenly died, she wasn’t allowed to go home to see him for one last time. The arduous journey, travel time, and other logistical problems were cited as reasons.

The Church also ensured total censorship and nuns were allowed no access to newspapers or TV channels except for Deepika and Shalom TV, which focus on the adulation of the Church. This censorship continued even as the rape case involving Franco Mulakkal, the Bishop of Jalandhar, caught fire. While the nun at the centre of the case was shamed by rumour-mongering fellow nuns, Kalapura, who supported her, registered her peaceful protest with other Kerala nuns, and gave multiple statements against the bishop on news channels.

Branded an outcaste because of her support to the nun, she was denied breakfast for many days in a row. Her utensils were segregated and she was forced to comply with orders of repeated transfers and demotions. Her request to publish her CD, and later her book, was denied. In the last few chapters, she talks about her sister, who fell in love with a man, and having no permission from the Church to marry him, had to escape from the hostel at night. The incident is an acute reminder of the stress under which nuns are forced to live.

Kalapura writes with conviction though the frequent quotations from the Bible to justify her actions also point towards her own indecisive state of mind as she questions the organisation while most around her act like robots — mechanically following the orders of their masters. Nandakumar K’s translation slightly tweaks the original adding spirit to the matter-of-fact writing. In the end, the reader is both appalled at the excesses of the Catholic church and struck by Sister Kalapura’s doughty spirit.

Kinshuk Gupta is the Associate Editor for Usawa Literary Review and the Poetry Editor for Jaggery Lit and Mithila Review.

From the agnostic’s perspective, organised religion works by ousting logic. Discourses and gatherings are venues for brainwashing believers into acting in accordance with the ultimate Truth, as defined by the concerned religious authority. The fear of God then becomes a way to tame thousands of the faithful who are only too willing to offer their labour and their hard-earned money to strengthen the religious establishment.

It is true that most religious bodies begin with noble intentions and, even in their darkest hour, offer respite to the distraught and the restless. Often, however, humanity’s malign side takes over — dominating and superseding the more benign aspects.

This trajectory is revealed in former nun Sister Lucy Kalapura’s book In the Name of the Lord about her experience with the Catholic Church. Her distrust in the clergy began in secondary school after she saw a priest touching a classmate inappropriately. Her intention to report the incident was stymied by her mother who insisted that she stay silent. Kalapura later learnt that her sister too had gone through the same humiliation. Still, as a young girl, Kalapura didn’t demand much from life except to be allowed to live in the company of Jesus. Going against the wishes of her Chachan (father) and Kunjaanja (elder brother), she followed in the footsteps of her elder sister and became a nun. It should have been a glorious initiation into the religious life but a succession of priests, Mother Superiors, and nuns jealous of every threat to their positions poisoned her pursuit of peace and transformed her world into a sickening hell.

Kalapura describes four incidents when she was caught off-guard by white-bearded priests who tried to get physically intimate with her. While predatory incidents like these seem rampant, the author states that nuns too, at times, initiate physical relationships spurred by sexual desire or the ambition to accrue power within the church hierarchy. Repressed homosexuality is common place as illustrated by the nun from Thalassery who persistently attempted to entice Sister Kalapura into her room, and the gay priest who confined and raped another. Kalapura believes relaxing the rules around chastity would be beneficial and stresses that personal choice must prevail in these decisions.

While these revelations might leave the reader aghast, what really sets this book apart is its central revelation about how the Church controls nuns’ access to money, behaving like a strict parent whose permission needs to be sought at every step and before every petty task.

Despite teaching in Catholic schools spread across the country, Kalapura only had some meagre money of her own. As with most nuns, she had to depend on the Church for basic needs including for a supply of undergarments and sanitary pads. The nuns were forced to use white rolls of cloth or pads with poor absorption qualities. Even after an emergency allowance was provided, nuns had to beg the Mother Superior to allow them to use pads. “We had to plead for undergarments. Undergarments from close-down sales of resellers or warehouse sales of manufacturers were collected in the Provincial House… The only option was to pick what was available, whether it fitted or not,” she says.

Worse, when Kalapura was working as a principal of a primary school in Bundi, near Kota, Rajasthan, and her father suddenly died, she wasn’t allowed to go home to see him for one last time. The arduous journey, travel time, and other logistical problems were cited as reasons.

The Church also ensured total censorship and nuns were allowed no access to newspapers or TV channels except for Deepika and Shalom TV, which focus on the adulation of the Church. This censorship continued even as the rape case involving Franco Mulakkal, the Bishop of Jalandhar, caught fire. While the nun at the centre of the case was shamed by rumour-mongering fellow nuns, Kalapura, who supported her, registered her peaceful protest with other Kerala nuns, and gave multiple statements against the bishop on news channels.

Branded an outcaste because of her support to the nun, she was denied breakfast for many days in a row. Her utensils were segregated and she was forced to comply with orders of repeated transfers and demotions. Her request to publish her CD, and later her book, was denied. In the last few chapters, she talks about her sister, who fell in love with a man, and having no permission from the Church to marry him, had to escape from the hostel at night. The incident is an acute reminder of the stress under which nuns are forced to live.

Kalapura writes with conviction though the frequent quotations from the Bible to justify her actions also point towards her own indecisive state of mind as she questions the organisation while most around her act like robots — mechanically following the orders of their masters. Nandakumar K’s translation slightly tweaks the original adding spirit to the matter-of-fact writing. In the end, the reader is both appalled at the excesses of the Catholic church and struck by Sister Kalapura’s doughty spirit.

Kinshuk Gupta is the Associate Editor for Usawa Literary Review and the Poetry Editor for Jaggery Lit and Mithila Review.