Review: India After 1947 by Rajmohan Gandhi

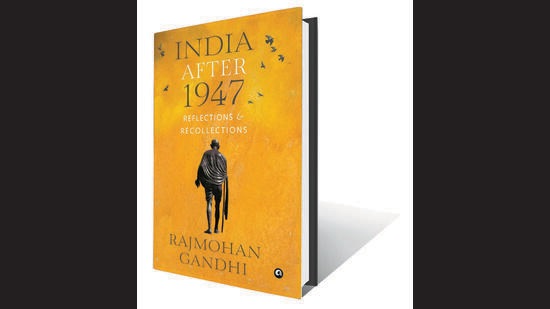

We are the country with the longest constitution in the world. We have, in the Mahabharata, the longest epic in the world. Even our police charge sheets are often minor epics, running into thousands of pages. The tendency to go to great lengths is not restricted to the written word alone. It is rare for a speaker with a mic in hand, even if it is only at the building society’s Resident Welfare Association meeting, to let go of it until it is more or less wrestled out of his, or, more rarely, her hands. Therefore, when I heard the title India After 1947: Reflections and Recollections, I expected a volume at least as thick as a brick. Instead, I was surprised to find a slim book little more than a hundred pages long.

It is a quick and often delightful read. The author, political scientist and historian Rajmohan Gandhi writes with felicity and grace to bring together, as the title suggests, some recollections from his long life of more than 87 years, and reflections on current trends such as Hindu nationalism.

As the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi from his paternal side and Chakravarti Rajagaopalachari from his maternal side, the author knew, with close familiarity, many of the stalwarts whose names dominate India’s modern history. He was also a witness to the relationship of those stalwarts with a figure that has dominated Indian politics for more than three decades now: the god Ram. Rajmohan Gandhi recollects, in the opening chapter of the book, joining his grandfather’s prayer meetings with his siblings and parents in Valmiki Colony, off today’s Mandir Marg in Delhi, and later in Birla House in Lutyens’ Delhi. He came to know well the Sanskrit verses recited at those prayer meetings. When sent to represent his school at a recitation competition at the local Ramakrishna Mission, he duly won an award which he received from Sarat Chandra Bose, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s elder brother.

“Pleading all his life and incessantly to Ram… trusting in his Ram, Gandhi, my grandfather, did not once refer either to Ram Janmabhoomi or to the mosque that stood there,” writes Rajmohan Gandhi. Nor, he adds, did his maternal grandfather, Rajaji, or Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, whom he met in his home in what was then, and for six decades after his death, Aurangzeb Road.

Rajmohan Gandhi’s previous books include a magisterial biography of Sardar Patel. Ever the historian, his reflections and recollections in this proto-memoir whose five chapters are really more in the nature of insightful essays delve with focused brevity on aspects of Indian history that are of contemporary relevance. Among these is Partition and the slogan of Akhand Bharat. Given the country’s history, “the unity that grew across virtually all of India in the 1900s, 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s seems a miracle,” writes Gandhi. The history he refers to in this context is of events such as the Great Revolt of 1857, which had failed “because the major Indian princes, including those of Baroda, Gwalior, Hyderabad, Mysore, and Kashmir, refused to lend even indirect support to the Revolt’s leaders”.

The miraculous unity crumbled with Partition. Gandhi traces some of the political and constitutional developments that led us there. He mentions the December 1930 wish expressed by Muhammad Iqbal for a consolidated Muslim state in northwestern India, and the series of articles by Lala Lajpat Rai in The Tribune in 1924 that had proposed a division of Punjab and Bengal into Hindu and Muslims majority portions. He also recounts British efforts at a negotiated settlement, such as the Cripps Mission of 1942, which promised India independence after the Second World War but also made that offer available to the princely states and individual provinces. Mahatma Gandhi, and later, the Congress Working Committee, rejected the offer, and passed a resolution stating it could not “think in terms of compelling the people of any territorial unit to remain in an Indian union against their declared and established will”. This essentially paved the way for Partition. While the author notes subsequent last-ditch efforts to prevent Partition, especially by Gandhi, the collapse of the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 – to which both the Muslim League and the Congress had initially agreed – is however omitted. The two personalities usually considered central to the collapse of that Plan are Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

While there may be such quibbles about the slant of the history in this account, no such doubts cloud the book as memoir. Several of the vignettes would be of particular interest to journalists, and to readers of this newspaper. The author’s father Devdas Gandhi was editor of the Hindustan Times, and Rajmohan Gandhi recalls growing up in an apartment in the floor below which teleprinters clickety-clacked and sub editors spiked uninteresting or dubious stories. Devdas Gandhi, he writes, was offered the position of India’s ambassador to Moscow in 1949 when he was editor of HT, by Nehru and Patel. He declined.

Rajmohan Gandhi himself has had a stint as resident editor of a newspaper, The Indian Express, or what is now The New Indian Express, in Chennai. He continues to care about journalists and journalism; this book is dedicated to “the unnamed Indian reporter or photographer, diligent and brave, female or male”. Among other interests he mentions is the organization earlier known as Moral Re-Armament and now as Initiatives of Change which has worked on peace building in various parts of the world.

When he had received his prize for recitation from Sarat Bose as a child, Gandhi writes, Bose had mentioned a book called Ideas Have Legs, a phrase that intrigued his mind and stayed there. The ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity, which emerged as the motto of the French Revolution, recur throughout this slim volume. In a world of information overload, the lucidity and brevity, and most of all, the distilled knowledge and wisdom with which it brings these ideas to bear on contemporary India makes it a book well worth reading.

Samrat Choudhury is an author and journalist. His most recent book is The Braided River: A Journey Along the Brahmaputra.

We are the country with the longest constitution in the world. We have, in the Mahabharata, the longest epic in the world. Even our police charge sheets are often minor epics, running into thousands of pages. The tendency to go to great lengths is not restricted to the written word alone. It is rare for a speaker with a mic in hand, even if it is only at the building society’s Resident Welfare Association meeting, to let go of it until it is more or less wrestled out of his, or, more rarely, her hands. Therefore, when I heard the title India After 1947: Reflections and Recollections, I expected a volume at least as thick as a brick. Instead, I was surprised to find a slim book little more than a hundred pages long.

It is a quick and often delightful read. The author, political scientist and historian Rajmohan Gandhi writes with felicity and grace to bring together, as the title suggests, some recollections from his long life of more than 87 years, and reflections on current trends such as Hindu nationalism.

As the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi from his paternal side and Chakravarti Rajagaopalachari from his maternal side, the author knew, with close familiarity, many of the stalwarts whose names dominate India’s modern history. He was also a witness to the relationship of those stalwarts with a figure that has dominated Indian politics for more than three decades now: the god Ram. Rajmohan Gandhi recollects, in the opening chapter of the book, joining his grandfather’s prayer meetings with his siblings and parents in Valmiki Colony, off today’s Mandir Marg in Delhi, and later in Birla House in Lutyens’ Delhi. He came to know well the Sanskrit verses recited at those prayer meetings. When sent to represent his school at a recitation competition at the local Ramakrishna Mission, he duly won an award which he received from Sarat Chandra Bose, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s elder brother.

“Pleading all his life and incessantly to Ram… trusting in his Ram, Gandhi, my grandfather, did not once refer either to Ram Janmabhoomi or to the mosque that stood there,” writes Rajmohan Gandhi. Nor, he adds, did his maternal grandfather, Rajaji, or Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, whom he met in his home in what was then, and for six decades after his death, Aurangzeb Road.

Rajmohan Gandhi’s previous books include a magisterial biography of Sardar Patel. Ever the historian, his reflections and recollections in this proto-memoir whose five chapters are really more in the nature of insightful essays delve with focused brevity on aspects of Indian history that are of contemporary relevance. Among these is Partition and the slogan of Akhand Bharat. Given the country’s history, “the unity that grew across virtually all of India in the 1900s, 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s seems a miracle,” writes Gandhi. The history he refers to in this context is of events such as the Great Revolt of 1857, which had failed “because the major Indian princes, including those of Baroda, Gwalior, Hyderabad, Mysore, and Kashmir, refused to lend even indirect support to the Revolt’s leaders”.

The miraculous unity crumbled with Partition. Gandhi traces some of the political and constitutional developments that led us there. He mentions the December 1930 wish expressed by Muhammad Iqbal for a consolidated Muslim state in northwestern India, and the series of articles by Lala Lajpat Rai in The Tribune in 1924 that had proposed a division of Punjab and Bengal into Hindu and Muslims majority portions. He also recounts British efforts at a negotiated settlement, such as the Cripps Mission of 1942, which promised India independence after the Second World War but also made that offer available to the princely states and individual provinces. Mahatma Gandhi, and later, the Congress Working Committee, rejected the offer, and passed a resolution stating it could not “think in terms of compelling the people of any territorial unit to remain in an Indian union against their declared and established will”. This essentially paved the way for Partition. While the author notes subsequent last-ditch efforts to prevent Partition, especially by Gandhi, the collapse of the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 – to which both the Muslim League and the Congress had initially agreed – is however omitted. The two personalities usually considered central to the collapse of that Plan are Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

While there may be such quibbles about the slant of the history in this account, no such doubts cloud the book as memoir. Several of the vignettes would be of particular interest to journalists, and to readers of this newspaper. The author’s father Devdas Gandhi was editor of the Hindustan Times, and Rajmohan Gandhi recalls growing up in an apartment in the floor below which teleprinters clickety-clacked and sub editors spiked uninteresting or dubious stories. Devdas Gandhi, he writes, was offered the position of India’s ambassador to Moscow in 1949 when he was editor of HT, by Nehru and Patel. He declined.

Rajmohan Gandhi himself has had a stint as resident editor of a newspaper, The Indian Express, or what is now The New Indian Express, in Chennai. He continues to care about journalists and journalism; this book is dedicated to “the unnamed Indian reporter or photographer, diligent and brave, female or male”. Among other interests he mentions is the organization earlier known as Moral Re-Armament and now as Initiatives of Change which has worked on peace building in various parts of the world.

When he had received his prize for recitation from Sarat Bose as a child, Gandhi writes, Bose had mentioned a book called Ideas Have Legs, a phrase that intrigued his mind and stayed there. The ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity, which emerged as the motto of the French Revolution, recur throughout this slim volume. In a world of information overload, the lucidity and brevity, and most of all, the distilled knowledge and wisdom with which it brings these ideas to bear on contemporary India makes it a book well worth reading.

Samrat Choudhury is an author and journalist. His most recent book is The Braided River: A Journey Along the Brahmaputra.