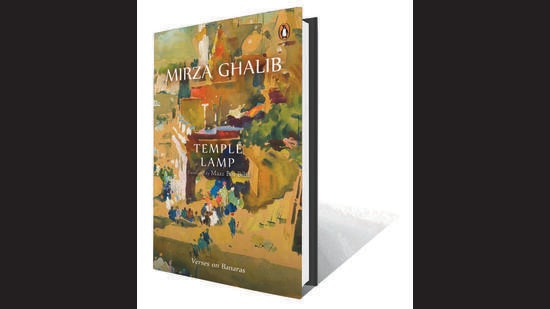

Review: Temple Lamp by Mirza Ghalib, translated by Maaz Bin Bilal

Mirza Ghalib’s andaaz-e-bayaan, we know, is aur (ie his style is extraordinary). But many of us, who relish his poems in Urdu or translated into English, might not know yet the extent of this aur. While Ghalib’s Urdu poetry remains popular, we can’t access another part of his work. “The bulk of his work was written in Persian… very little of his Persian poetry has been translated into English,” says the introduction to the English translation of Ghalib’s long poem in Persian, Chirag-e-dair. Temple Lamp is said to be the first English translation in entirety of Ghalib’s poem on Banaras, and if so, its publication is a milestone for lovers of Ghalib’s poetry. There are other reasons too, why the translation is important.

For one, as pointed out in the translator Maaz Bin Bilal’s introduction, Temple Lamp disproves the widespread notion of Ghalib as “primarily a poet of grief”. He was more. His only long poem about a city does lament, but there is plenty it celebrates. A poet and academic himself, Maaz Bin Bilal believes it “illustrates Ghalib’s penchant for physical beauty, his ability to perceive and represent pleasure and joy, and his zest for life”.

The introduction dwells briefly on Ghalib’s ancestry, his personal history, cultural heritage and pride in his “Indo-Turkish lineage”, his disinclination to find employment, and his cosmopolitan outlook. Such details flesh him out as a person. The brief account of Ghalib’s output in Persian also expands the reader’s understanding of him as a multilingual poet and a man whose faith was “cosmopolitan and multi-cultural”. This unique lens he brought to Banaras. The translator says it was through “a Persian cultural inheritance” and “from the perspective of arguably the best poet of the nineteenth century, from the perspective of a Hindustani Muslim” that Banaras is seen. The background also explains why he went to Banaras and why he stayed there for three months to heal physically and in spirit. The scholarly introduction revealed many layers of the poem to me.

In translation, Chirag-e-dair loses a few things – rhyme and metre, mainly. Also lost is play on meanings sometimes, which is flagged by footnotes. This enhanced the pleasure of my reading. In most places, one original couplet is translated into two English ones, a strategy that I found delightful. It helps retain the “essential feature” of each of the shers in Persian: this is “the even division of the verse with its exposition in the first line and the resolution or response in the second”. The method allows the couplet to keep its “balance” in translation and also bear the rabt, “a bond or link which works like a spark or charge of contact” between the two lines of the couplet, says Maaz Bin Bilal.

The translator’s choice to use everyday English makes the translation sound natural and relatable, although it is inevitable that in English, a few metaphors and references, “harp of lament”, for instance, might sound old-fashioned. What pleasantly surprised me was just how many of Ghalib’s references and metaphors sounded fresh. The season of autumn turns into a “sandalwood mark” on the forehead of Banaras. And this about women bathing in the river: “their newness grants/ shape to the body of the water”. There’s plenty more where that came from.

Even if you don’t know Persian, you can savour the sound of the original couplets on your tongue as they are printed in Roman script and paired with their English versions. Not knowing Persian, I enjoyed Temple Lamp as a poem written originally in English, endearing itself to my ear, and able to nimbly convey the heightened lyricism we associate with Ghalib.

Ghalib’s embrace of cultural confluence as seen in Temple Lamp also made me look at him as a gentle political symbol of great relevance to our times. For instance, (as the translator points out) there are 108 couplets in the Banaras poem. A Muslim, which Ghalib was, might not think this number sacred. Hindus, Buddhists and Jains might — a fact to which he was clearly sensitive. Ghalib writes of Banaras reverentially: “Each fleck of dirt here/ in its ecstasy is a temple,/ every thorn with its verdure/ becomes paradise”. Then, Ghalib asks a clairvoyant why this world with folks doing terrible things has not yet faced qayamat. The clairvoyant responds: “Pointing to Kashi/ with a gesture, he smiled/ and said, it is for the sake/ of this town./ It is unbearable/ to the Maker– / that this colourful city/ be razed./” Could praise for a city, for a culture not of one’s family, be more open-hearted?

The poem’s arc, which begins with Ghalib’s lament at having left Delhi on a long journey, and his separation from his friends, moves to his happiness at being in Banaras and his celebration of its spiritual and sensual aspects, and finally his convincing himself to leave this “paradise” and return to responsibilities and folks close to him.

Did Ghalib also, as the translator speculates, have a love affair in Banaras? Maaz Bin Bilal mentions clues in the introduction, which might add layers to the poem’s powerfully sensual parts. One couplet goes: The idolatrous beauties (of Banaras)/ are made of the fire of Tur,/ with god-given glow from head to toe./ May they be safe from the evil eye. (Tur is the mountain, writes the translator, in the “Quranic account of Musa’s encounter with Allah”. Another couplet, more impassioned, turns vernal with a metaphor from the Persosphere: With their colourful ways,/ they drive us out of our mind;/ they are springtime in bed,/ the Nowruz is their embrace./ (Could ‘they’ mean ‘her’, as the translator says to leave the possibility open, so was Ghalib referring to a specific woman?) A little later arrives this couplet: Embodied by water,/ they cause a storm in the river,/ a hundred fish hearts/ beat in the chest (of the lover). I mustn’t give away spoilers save for this steamy part where pearls melt into water/ in their shells. Phew!

This, too, is Ghalib.

Suhit Kelkar is an independent journalist. He lives in Mumbai.

Mirza Ghalib’s andaaz-e-bayaan, we know, is aur (ie his style is extraordinary). But many of us, who relish his poems in Urdu or translated into English, might not know yet the extent of this aur. While Ghalib’s Urdu poetry remains popular, we can’t access another part of his work. “The bulk of his work was written in Persian… very little of his Persian poetry has been translated into English,” says the introduction to the English translation of Ghalib’s long poem in Persian, Chirag-e-dair. Temple Lamp is said to be the first English translation in entirety of Ghalib’s poem on Banaras, and if so, its publication is a milestone for lovers of Ghalib’s poetry. There are other reasons too, why the translation is important.

For one, as pointed out in the translator Maaz Bin Bilal’s introduction, Temple Lamp disproves the widespread notion of Ghalib as “primarily a poet of grief”. He was more. His only long poem about a city does lament, but there is plenty it celebrates. A poet and academic himself, Maaz Bin Bilal believes it “illustrates Ghalib’s penchant for physical beauty, his ability to perceive and represent pleasure and joy, and his zest for life”.

The introduction dwells briefly on Ghalib’s ancestry, his personal history, cultural heritage and pride in his “Indo-Turkish lineage”, his disinclination to find employment, and his cosmopolitan outlook. Such details flesh him out as a person. The brief account of Ghalib’s output in Persian also expands the reader’s understanding of him as a multilingual poet and a man whose faith was “cosmopolitan and multi-cultural”. This unique lens he brought to Banaras. The translator says it was through “a Persian cultural inheritance” and “from the perspective of arguably the best poet of the nineteenth century, from the perspective of a Hindustani Muslim” that Banaras is seen. The background also explains why he went to Banaras and why he stayed there for three months to heal physically and in spirit. The scholarly introduction revealed many layers of the poem to me.

In translation, Chirag-e-dair loses a few things – rhyme and metre, mainly. Also lost is play on meanings sometimes, which is flagged by footnotes. This enhanced the pleasure of my reading. In most places, one original couplet is translated into two English ones, a strategy that I found delightful. It helps retain the “essential feature” of each of the shers in Persian: this is “the even division of the verse with its exposition in the first line and the resolution or response in the second”. The method allows the couplet to keep its “balance” in translation and also bear the rabt, “a bond or link which works like a spark or charge of contact” between the two lines of the couplet, says Maaz Bin Bilal.

The translator’s choice to use everyday English makes the translation sound natural and relatable, although it is inevitable that in English, a few metaphors and references, “harp of lament”, for instance, might sound old-fashioned. What pleasantly surprised me was just how many of Ghalib’s references and metaphors sounded fresh. The season of autumn turns into a “sandalwood mark” on the forehead of Banaras. And this about women bathing in the river: “their newness grants/ shape to the body of the water”. There’s plenty more where that came from.

Even if you don’t know Persian, you can savour the sound of the original couplets on your tongue as they are printed in Roman script and paired with their English versions. Not knowing Persian, I enjoyed Temple Lamp as a poem written originally in English, endearing itself to my ear, and able to nimbly convey the heightened lyricism we associate with Ghalib.

Ghalib’s embrace of cultural confluence as seen in Temple Lamp also made me look at him as a gentle political symbol of great relevance to our times. For instance, (as the translator points out) there are 108 couplets in the Banaras poem. A Muslim, which Ghalib was, might not think this number sacred. Hindus, Buddhists and Jains might — a fact to which he was clearly sensitive. Ghalib writes of Banaras reverentially: “Each fleck of dirt here/ in its ecstasy is a temple,/ every thorn with its verdure/ becomes paradise”. Then, Ghalib asks a clairvoyant why this world with folks doing terrible things has not yet faced qayamat. The clairvoyant responds: “Pointing to Kashi/ with a gesture, he smiled/ and said, it is for the sake/ of this town./ It is unbearable/ to the Maker– / that this colourful city/ be razed./” Could praise for a city, for a culture not of one’s family, be more open-hearted?

The poem’s arc, which begins with Ghalib’s lament at having left Delhi on a long journey, and his separation from his friends, moves to his happiness at being in Banaras and his celebration of its spiritual and sensual aspects, and finally his convincing himself to leave this “paradise” and return to responsibilities and folks close to him.

Did Ghalib also, as the translator speculates, have a love affair in Banaras? Maaz Bin Bilal mentions clues in the introduction, which might add layers to the poem’s powerfully sensual parts. One couplet goes: The idolatrous beauties (of Banaras)/ are made of the fire of Tur,/ with god-given glow from head to toe./ May they be safe from the evil eye. (Tur is the mountain, writes the translator, in the “Quranic account of Musa’s encounter with Allah”. Another couplet, more impassioned, turns vernal with a metaphor from the Persosphere: With their colourful ways,/ they drive us out of our mind;/ they are springtime in bed,/ the Nowruz is their embrace./ (Could ‘they’ mean ‘her’, as the translator says to leave the possibility open, so was Ghalib referring to a specific woman?) A little later arrives this couplet: Embodied by water,/ they cause a storm in the river,/ a hundred fish hearts/ beat in the chest (of the lover). I mustn’t give away spoilers save for this steamy part where pearls melt into water/ in their shells. Phew!

This, too, is Ghalib.

Suhit Kelkar is an independent journalist. He lives in Mumbai.