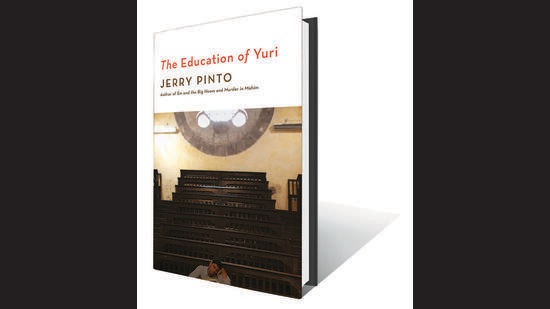

Review: The Education of Yuri byJerry Pinto

Yuri Fonseca of Mahim, raised without family but for his uncle, has grown up lonely. Now, he struggles with making friends when the story begins with his joining senior college; his sense of embarrassment, awkwardness and insecurity sting him. Called padri ka bachcha at school and very culturally different from his peers, he has grown up hurt. In college, he gives in to the enthusiasms and causes of others, which he abandons when following through is needed. When included in a group, he finds himself drifting away. He longs for friendship without knowing how to keep friends close. He seeks his purpose and a firm idea of his values. In the grip of existential queries, he transgresses a few socially accepted boundaries, which bring out the grey aspects of his personality. You find yourself not pitying or idealising his struggle, but you feel for him.

This story of growing up is nostalgic, compassionate and frequently hilarious, and exceptional for its main character and its evocation of its setting and time, Bombay of the 1980s.

How vividly Yuri puts you in the shoes of this middle class youth studying for a Bachelor’s in Arts in artsy Kala Ghoda, and helps you see through his eyes as a huge array of relationships and neighbourhoods unspools for him. A Bombay is evoked which had just put behind itself the defilements of freedoms during the Emergency, and was roiled by the great millworkers’ strike which transformed it forever, and was shocked by the assassination of Indira Gandhi in Delhi followed by massacres of Sikhs. In that period, Communism had lost ground in Bombay and Marathi nativism was yet to become dominant.

These momentous events colour Yuri’s life in Elphinstone College (which is one of the real places mentioned) in the background except for a few important passages. For the most part, look out for Yuri’s college life with hilarious classroom interactions, his jokey banter with friends, intense conversations with the girl whom he is seeing, and one mind-bending, amnesiac evening filled with transgression and adventure.

Yuri’s Bombay is years away from morphing into Mumbai, a city I love and dread, which offers unbelievable personal freedom to make yourself while exacting champion-level productivity, and which seethes, quite obviously, with communal and class hatred though less than other Indian cities. I can’t borrow someone else’s nostalgia for that old Bombay, which I’ve only heard of. But it sure looks like some of that place would do today’s Mumbai good.

Yuri’s Bombay is – overkill to use the phrase “more democratic” – an open place, which creates circumstances where the Richie-Riches and the getting-by-nicelys and the scraping-bys (Yuri) shoot the breeze in the same public spaces and very matter-of-factly. Here even awkward, khadi-clad and English-speaking Yuri finds friendships and other intimacies. His first real friend, endearingly kooky Muzammil, hails from Pedder Road, no less. Were Yuri set in today’s Mumbai, Yuri-Muzammil’s bromance might or might not happen, as Muzammil would likely be educated in an ‘international school’ (fees: a few lakh rupees a month), then go to the UK or US for college. Their paths might not cross.

And Yuri’s classmate Arif, with many jaanoos, might possibly find it a little harder to conduct interfaith romances in today’s Mumbai. And so I cherish the scene where Arif takes Yuri to eat an omelette, and the smell of onion and garlic, says Arif, “means no kisses” from his girlfriend, who is Jain. Arif gladly orders an omelette without these ingredients. Having grown up on the extended outskirts of Mumbai, I remember teenaged friends dating outside their faith negotiating similar charming compromises.

Yuri, too, is having what today you might call a “situationship” with a girl of Hindu heritage, Bhavna. In Yuri’s words, “They (he and Bhavna) both knew it wasn’t love, and neither of them was sad about this. Which was a good thing, he supposed.” Bhavna is a government official’s daughter who asks questions of her own privilege and of Yuri’s sensibilities as a man, and negotiates her own internal conflicts.

There’s another classmate Bimli, who eventually joins her Naxalite group in Chandrapur to overthrow the Indian state. And Julio, Yuri’s uncle, reminds me of actual people I’ve met in Mumbai; a devout Roman Catholic, a lay ascetic, inspired by Gandhi, attired in khadi. Julio renounces his wish to be ordained as a priest in order to raise Yuri.

Even the minor characters, whom you affectionately or not-so-affectionately might call Bombay namoonas, are memorable. The hefty, lachrymose and fabulously named Tehmtan Bodybuilder, who in one scene melodramatically invokes Khodaai; the harried commuters of Churchgate and Mahim who exhibit a variant of road rage you might call “walker’s wrath”; the footpath-based bookseller Premadasa, who scans maybe your look or clothes or manner to recommend intriguing titles as cannily as his real-life counterparts; the sassy waiter at the Milk Bar who brings oily, tasty dishes of “delectable Bombayness” with a generous side of Bambaiya Hindi. Real-life folks iconically identified with the city, too, make cameo appearances. Yuri meets, in two poetry circles at Kala Ghoda, the poet-pitamahs Nissim Ezekiel and Adil Jussawala.

All in all, Yuri doesn’t cheerlead for its evocation of Bombay, and eschews romanticising the past. While dwelling on that cosmopolitanism, it also holds it to the light so you see the gaps. 1980s Bombay is evoked so vividly, it gets under your skin, and you might just mistake it for memory.

Suhit Bombaywala’s journalism and imaginative writing are published in India and abroad.

Yuri Fonseca of Mahim, raised without family but for his uncle, has grown up lonely. Now, he struggles with making friends when the story begins with his joining senior college; his sense of embarrassment, awkwardness and insecurity sting him. Called padri ka bachcha at school and very culturally different from his peers, he has grown up hurt. In college, he gives in to the enthusiasms and causes of others, which he abandons when following through is needed. When included in a group, he finds himself drifting away. He longs for friendship without knowing how to keep friends close. He seeks his purpose and a firm idea of his values. In the grip of existential queries, he transgresses a few socially accepted boundaries, which bring out the grey aspects of his personality. You find yourself not pitying or idealising his struggle, but you feel for him.

This story of growing up is nostalgic, compassionate and frequently hilarious, and exceptional for its main character and its evocation of its setting and time, Bombay of the 1980s.

How vividly Yuri puts you in the shoes of this middle class youth studying for a Bachelor’s in Arts in artsy Kala Ghoda, and helps you see through his eyes as a huge array of relationships and neighbourhoods unspools for him. A Bombay is evoked which had just put behind itself the defilements of freedoms during the Emergency, and was roiled by the great millworkers’ strike which transformed it forever, and was shocked by the assassination of Indira Gandhi in Delhi followed by massacres of Sikhs. In that period, Communism had lost ground in Bombay and Marathi nativism was yet to become dominant.

These momentous events colour Yuri’s life in Elphinstone College (which is one of the real places mentioned) in the background except for a few important passages. For the most part, look out for Yuri’s college life with hilarious classroom interactions, his jokey banter with friends, intense conversations with the girl whom he is seeing, and one mind-bending, amnesiac evening filled with transgression and adventure.

Yuri’s Bombay is years away from morphing into Mumbai, a city I love and dread, which offers unbelievable personal freedom to make yourself while exacting champion-level productivity, and which seethes, quite obviously, with communal and class hatred though less than other Indian cities. I can’t borrow someone else’s nostalgia for that old Bombay, which I’ve only heard of. But it sure looks like some of that place would do today’s Mumbai good.

Yuri’s Bombay is – overkill to use the phrase “more democratic” – an open place, which creates circumstances where the Richie-Riches and the getting-by-nicelys and the scraping-bys (Yuri) shoot the breeze in the same public spaces and very matter-of-factly. Here even awkward, khadi-clad and English-speaking Yuri finds friendships and other intimacies. His first real friend, endearingly kooky Muzammil, hails from Pedder Road, no less. Were Yuri set in today’s Mumbai, Yuri-Muzammil’s bromance might or might not happen, as Muzammil would likely be educated in an ‘international school’ (fees: a few lakh rupees a month), then go to the UK or US for college. Their paths might not cross.

And Yuri’s classmate Arif, with many jaanoos, might possibly find it a little harder to conduct interfaith romances in today’s Mumbai. And so I cherish the scene where Arif takes Yuri to eat an omelette, and the smell of onion and garlic, says Arif, “means no kisses” from his girlfriend, who is Jain. Arif gladly orders an omelette without these ingredients. Having grown up on the extended outskirts of Mumbai, I remember teenaged friends dating outside their faith negotiating similar charming compromises.

Yuri, too, is having what today you might call a “situationship” with a girl of Hindu heritage, Bhavna. In Yuri’s words, “They (he and Bhavna) both knew it wasn’t love, and neither of them was sad about this. Which was a good thing, he supposed.” Bhavna is a government official’s daughter who asks questions of her own privilege and of Yuri’s sensibilities as a man, and negotiates her own internal conflicts.

There’s another classmate Bimli, who eventually joins her Naxalite group in Chandrapur to overthrow the Indian state. And Julio, Yuri’s uncle, reminds me of actual people I’ve met in Mumbai; a devout Roman Catholic, a lay ascetic, inspired by Gandhi, attired in khadi. Julio renounces his wish to be ordained as a priest in order to raise Yuri.

Even the minor characters, whom you affectionately or not-so-affectionately might call Bombay namoonas, are memorable. The hefty, lachrymose and fabulously named Tehmtan Bodybuilder, who in one scene melodramatically invokes Khodaai; the harried commuters of Churchgate and Mahim who exhibit a variant of road rage you might call “walker’s wrath”; the footpath-based bookseller Premadasa, who scans maybe your look or clothes or manner to recommend intriguing titles as cannily as his real-life counterparts; the sassy waiter at the Milk Bar who brings oily, tasty dishes of “delectable Bombayness” with a generous side of Bambaiya Hindi. Real-life folks iconically identified with the city, too, make cameo appearances. Yuri meets, in two poetry circles at Kala Ghoda, the poet-pitamahs Nissim Ezekiel and Adil Jussawala.

All in all, Yuri doesn’t cheerlead for its evocation of Bombay, and eschews romanticising the past. While dwelling on that cosmopolitanism, it also holds it to the light so you see the gaps. 1980s Bombay is evoked so vividly, it gets under your skin, and you might just mistake it for memory.

Suhit Bombaywala’s journalism and imaginative writing are published in India and abroad.