Review: The Line of Mercy by Tarun Tejpal

Author and journalist Tarun Tejpal, who wrote The Alchemy of Desire (2006), The Story of My Assassins (2010) and The Valley of Masks (2011) is back with a new novel called The Line of Mercy (2022). He is in fine form, addressing existential questions with the mix of seriousness and humour that only a skilled craftsman is capable of.

This 750-page tome comes a year after the trial court in Mapusa, Goa, acquitted Tejpal of all charges filed by the police – including sexual harassment and rape. The seven months he spent in prison until the Supreme Court granted him bail seem to have played a defining role in shaping the form and content of The Line of Mercy.

The novel is set “in the thick air of a coastal town, inside the iron bars manufactured by the laws of men.” Rather than a story with a beginning, middle and end, what you must look out for is the cast of characters that Tejpal serves up. They are not easy to label as villains because Tejpal has a substantial back story for each one – a story that is a slap in the face of every stereotype, a story that evokes a range of emotions, a story that will make you wonder why we, as a society, are so enthusiastic about retributive justice knowing its many limitations.

“Everyone inside the iron bars was innocent. Even those who had committed murder and rape – and shyly admitted to it – knew that they were innocent,” writes Tejpal. You might ask who gets to decide whether someone is innocent or not, especially with the kind of criminal justice system that we have in India. “Not in the crude language of the law and its makers but in the infinitely subtler script of karma. This is logic only those in hell – inside or outside the iron bars – ever know,” he adds. This needs to be read in context, for meaning is only provisional.

Some readers might stay away from the book as they believe Tejpal to be guilty despite the court’s decision exonerating him. Others might choose to read for the author’s ringside view of the hells that he might have personally seen. In either case, looking for moments that could precisely map fiction onto autobiography might be a futile enterprise; insulting not only to the writer’s intelligence but also the reader’s common sense. The book is far more complex. It is also fairly gloomy but the romance, passion and comedy take the sharp edge off the darkness.

The Line of Mercy reminded me of three recent works of non-fiction that capture what life in jail looks like – hierarchies, routines, survival skills, economics of bribery, friendships and rivalries, and unforeseen kindnesses. Each one is excellent – Hamid Ansari’s book Hamid: The Story of My Captivity, Survival and Freedom (2020) co-authored with Geeta Mohan, Kafeel Khan’s book The Gorakhpur Hospital Tragedy: A Doctor’s Memoir of a Deadly Medical Crisis (2021) and TJ Joseph’s book A Thousand Cuts: An Innocent Question and Deadly Answers (2021) translated from Malayalam into English by Nandakumar K.

While the other authors are protagonists in their own books, Tejpal isn’t. His writerly gifts are deployed to give readers a fuller and deeper sense of those who have been banished by the law to the “frantic soup of sadness and madness” that they keep swimming and drowning in. Here, you meet a “hustling medical representative cutting sharp deals with doctors”, construction labourers caught for “snaring turtles from a swamp”, men who are insecure about their masculinity and suspect that their wives are on them, and people who serve VIPs in need of staff to “wash and clean and fetch and carry for them”.

This could be called “a novel of ideas” since the characters remain somewhat secondary to issues and debates. Tejpal’s narrative pauses every now and again to offer reflections that touch on things beyond his fictional universe. Sample this bit on non-violence: “Polished men wearing expensive perfumes spend hours watching brutal cinema and television because it fills an aching hole in their soul created by politeness and civilization. Unpolished men feel a primal pleasure when they puncture skin and shatter bone.”

The author devotes many pages to a discussion of the chaos that ensues when a love match is struck by heterosexual couples from different religious or caste backgrounds. They have to keep their youthful passion in check if they want to avoid the wrath of elders who are all too willing to spill blood if that is the price to protect the honour of their forefathers. Of course, Tejpal does question how honourable it really is to come in the way of lovers feverishly stealing glances, writing poetry, and looking desperately for a safe place to have sex. When they resolve to give a damn about their kinsfolk, the worst happens. There is no coming back.

Tejpal also directs his sharp pen to a critique of religious zealots who use their faith to beat their own drum with a fake show of superiority. They do not see the irony in destroying life and property in the name of the creator. The novel is fairly didactic but this is not much of a problem because the prose is well crafted and compelling. It alternates between sublime and ludicrous, erotic and ghastly.

“Men judge others to absolve themselves,” he writes. “There is no intoxicant in the world quite as heady as sanctimony… righteousness has the enduring warmth of an ever-regenerating banyan. It grows fresh limbs. It creates its own forest.” This is spot-on and reminded me of that idiom advising people who live in glass houses to not throw stones. Thankfully, Tejpal finds new and interesting ways to speak old truths.

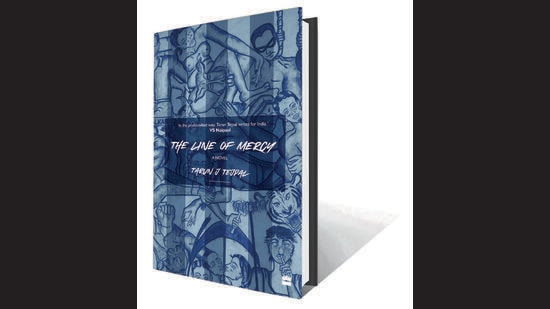

I found myself looking at the cover every time I took a break from reading. It is a painting by Amita Bhatt – charcoal and oil stick on canvas – titled The Line of Mercy (2017), which reminds me of Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica (1937) that memorializes the bombing of a Spanish village by the Nazis on behalf of General Franco. This comparison seems pertinent as the rise of the Hindu right wing – and violence directed at Indian Muslims – are important themes for Tejpal. He shows us that ghettoization is as prevalent in prison as it is outside. The cell that Muslims are thrown into is called – no surprises here – Pakistan.

For me, the strongest part of the book is Tejpal’s digression on fame. He calls it the worst of all narcotics. He writes, “The best people in the world are never known to anyone beyond whose lives they directly touch.” Humility is what marks them out; not the reach of their renown. This is a good lesson for many, especially do-gooders who cannot stop tweeting about every minor accomplishment.

Chintan Girish Modi is an independent writer, journalist and book reviewer.

Author and journalist Tarun Tejpal, who wrote The Alchemy of Desire (2006), The Story of My Assassins (2010) and The Valley of Masks (2011) is back with a new novel called The Line of Mercy (2022). He is in fine form, addressing existential questions with the mix of seriousness and humour that only a skilled craftsman is capable of.

This 750-page tome comes a year after the trial court in Mapusa, Goa, acquitted Tejpal of all charges filed by the police – including sexual harassment and rape. The seven months he spent in prison until the Supreme Court granted him bail seem to have played a defining role in shaping the form and content of The Line of Mercy.

The novel is set “in the thick air of a coastal town, inside the iron bars manufactured by the laws of men.” Rather than a story with a beginning, middle and end, what you must look out for is the cast of characters that Tejpal serves up. They are not easy to label as villains because Tejpal has a substantial back story for each one – a story that is a slap in the face of every stereotype, a story that evokes a range of emotions, a story that will make you wonder why we, as a society, are so enthusiastic about retributive justice knowing its many limitations.

“Everyone inside the iron bars was innocent. Even those who had committed murder and rape – and shyly admitted to it – knew that they were innocent,” writes Tejpal. You might ask who gets to decide whether someone is innocent or not, especially with the kind of criminal justice system that we have in India. “Not in the crude language of the law and its makers but in the infinitely subtler script of karma. This is logic only those in hell – inside or outside the iron bars – ever know,” he adds. This needs to be read in context, for meaning is only provisional.

Some readers might stay away from the book as they believe Tejpal to be guilty despite the court’s decision exonerating him. Others might choose to read for the author’s ringside view of the hells that he might have personally seen. In either case, looking for moments that could precisely map fiction onto autobiography might be a futile enterprise; insulting not only to the writer’s intelligence but also the reader’s common sense. The book is far more complex. It is also fairly gloomy but the romance, passion and comedy take the sharp edge off the darkness.

The Line of Mercy reminded me of three recent works of non-fiction that capture what life in jail looks like – hierarchies, routines, survival skills, economics of bribery, friendships and rivalries, and unforeseen kindnesses. Each one is excellent – Hamid Ansari’s book Hamid: The Story of My Captivity, Survival and Freedom (2020) co-authored with Geeta Mohan, Kafeel Khan’s book The Gorakhpur Hospital Tragedy: A Doctor’s Memoir of a Deadly Medical Crisis (2021) and TJ Joseph’s book A Thousand Cuts: An Innocent Question and Deadly Answers (2021) translated from Malayalam into English by Nandakumar K.

While the other authors are protagonists in their own books, Tejpal isn’t. His writerly gifts are deployed to give readers a fuller and deeper sense of those who have been banished by the law to the “frantic soup of sadness and madness” that they keep swimming and drowning in. Here, you meet a “hustling medical representative cutting sharp deals with doctors”, construction labourers caught for “snaring turtles from a swamp”, men who are insecure about their masculinity and suspect that their wives are on them, and people who serve VIPs in need of staff to “wash and clean and fetch and carry for them”.

This could be called “a novel of ideas” since the characters remain somewhat secondary to issues and debates. Tejpal’s narrative pauses every now and again to offer reflections that touch on things beyond his fictional universe. Sample this bit on non-violence: “Polished men wearing expensive perfumes spend hours watching brutal cinema and television because it fills an aching hole in their soul created by politeness and civilization. Unpolished men feel a primal pleasure when they puncture skin and shatter bone.”

The author devotes many pages to a discussion of the chaos that ensues when a love match is struck by heterosexual couples from different religious or caste backgrounds. They have to keep their youthful passion in check if they want to avoid the wrath of elders who are all too willing to spill blood if that is the price to protect the honour of their forefathers. Of course, Tejpal does question how honourable it really is to come in the way of lovers feverishly stealing glances, writing poetry, and looking desperately for a safe place to have sex. When they resolve to give a damn about their kinsfolk, the worst happens. There is no coming back.

Tejpal also directs his sharp pen to a critique of religious zealots who use their faith to beat their own drum with a fake show of superiority. They do not see the irony in destroying life and property in the name of the creator. The novel is fairly didactic but this is not much of a problem because the prose is well crafted and compelling. It alternates between sublime and ludicrous, erotic and ghastly.

“Men judge others to absolve themselves,” he writes. “There is no intoxicant in the world quite as heady as sanctimony… righteousness has the enduring warmth of an ever-regenerating banyan. It grows fresh limbs. It creates its own forest.” This is spot-on and reminded me of that idiom advising people who live in glass houses to not throw stones. Thankfully, Tejpal finds new and interesting ways to speak old truths.

I found myself looking at the cover every time I took a break from reading. It is a painting by Amita Bhatt – charcoal and oil stick on canvas – titled The Line of Mercy (2017), which reminds me of Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica (1937) that memorializes the bombing of a Spanish village by the Nazis on behalf of General Franco. This comparison seems pertinent as the rise of the Hindu right wing – and violence directed at Indian Muslims – are important themes for Tejpal. He shows us that ghettoization is as prevalent in prison as it is outside. The cell that Muslims are thrown into is called – no surprises here – Pakistan.

For me, the strongest part of the book is Tejpal’s digression on fame. He calls it the worst of all narcotics. He writes, “The best people in the world are never known to anyone beyond whose lives they directly touch.” Humility is what marks them out; not the reach of their renown. This is a good lesson for many, especially do-gooders who cannot stop tweeting about every minor accomplishment.

Chintan Girish Modi is an independent writer, journalist and book reviewer.