Salil Tripathi – “These writers exemplify courage in its rawest form”

How did you and artist Shilpa Gupta end up working together on this anthology? What skills, expertise, and institutional resources did each of you bring to this book project?

In February 2017 at a dinner at Kekee Manzil, the delightful home of my good friend Shireen Gandhy of the Chemould Prescott Road Gallery in Bombay, Shireen introduced me to Shilpa. She had told Shilpa about my book The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and Its Unquiet Legacy (2014), and was keen that we meet since Shilpa had made three shows around the Indo-Bangladesh borderland.

We met at Shilpa’s studio again a few days later and spoke of the many common areas of interest. Since then, it has been a privilege and honour for me to work with someone as gifted and committed as Shilpa. She probed deeply about my writing, read all my books, and I saw more of her art at her studio over several visits and at a few shows.

We also realised we were both at the National Gallery of Modern Art at its opening in 1997 in Bombay, when there was a show on the Progressive Artists; I was mingling with artists and she was among the JJ School of Art students with a banner that said “Husain, we miss you”. MF Husain had left Bombay to live in self-imposed exile at that time because he was a victim of ceaseless, frivolous persecution in India. That scene opens my first book Offence: The Hindu Case (2009) though I had not known Shilpa then.

Shilpa started getting my articles on a mailing list I maintain, and send to friends who’d like to read what I write. One such email was a speech I gave in Bombay in April 2017. It was to mark the silver jubilee of Abhidhanantar – the Marathi journal that the poet and publisher Hemant Divate publishes – and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences had organised a poetry festival on its Bombay campus with leading Indian poets, including Jayanta Mahapatra, Manglesh Dabral, and many other stalwarts. Ashwani Kumar was the magnet that attracted us.

I was invited to give a keynote address, where I spoke about the role of a poet as a dissident, as the one who protests, and who also suffers. This was at the time when poets, writers and artists were returning national awards in India because of their anger over state inaction in the face of rising intolerance. In my address, I recounted examples over hundreds of years, of poets around the world, who had been jailed or killed, but who persisted.

Shilpa liked that speech. She has worked for years on politically charged and challenging themes, including the borders in our minds and on the frontier, censorship of books, the impossibility of telling if a bottle of blood belongs to one faith or another, and other provocative displays of public art that force us to think. These are the themes that move me too.

She had written a proposal for a sound installation project based on voices of one hundred writers from an earlier installation piece of hers from 2011 – called Someone Else – of 100 books written anonymously or under pseudonyms as many of the writers had faced censorship. But my speech made Shilpa take a “detour”, as she puts it to me; she began a deep dive, researching ceaselessly on poets who had been imprisoned. She came across many moving stories, including many I had not mentioned and some I wasn’t aware of, and that made her want to share such stories from the past and present.

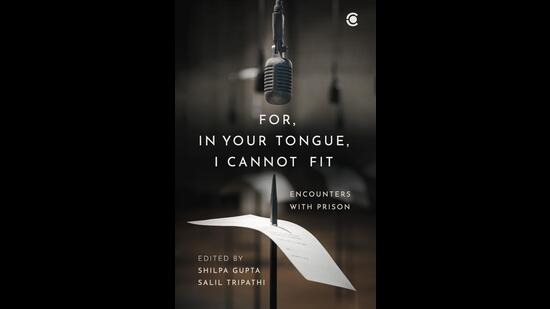

In a little over a year, she had conceptualised this astonishingly powerful sound installation – For In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit where you see, in a dimly lit room, spikes pierce through sheets of paper on which there are fragments of poems. The black microphones hanging from the ceiling don’t amplify your voice, but you hear the soft voices in many languages, murmurs of persecuted poets, haunting you.

She first showed the installation in Baku, and later in Brisbane, the Edinburgh Art Festival, Venice Biennale, Kochi Biennale, the Barbican in London, and the Dallas Contemporary. I joined her in Edinburgh and Kochi, where we spoke about the work, what inspired her, and what had drawn me to the poets, and how our collaboration happened. She wanted the installation to stay vivid, and so the idea of the book came about. We would use extracts of poems from the majority of the poets in the installation, and seek out essays, poems, or conversations with writers from around the world, who were either persecuted themselves, or knew those who were persecuted, or were moved by their stories to write.

How did your experience of chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and co-chairing English PEN’s Writers at Risk Committee shape this anthology?

Immensely! I could not have done it without having been engaged with PEN. I had co-chaired the Writers at Risk Committee in the UK with my friend, the novelist Kamila Shamsie, and from 2015 to 2021 I chaired the Writers in Prison Committee internationally. Both those stints reminded me daily of the writers and poets who are in jail only for expressing their views that those in power don’t like. Sara Whyatt, a senior researcher who has worked with PEN, built on the hours of research Shilpa and her team had put together on each poet, and she wrote the biographical entries. Other writers who are PEN members, including current president, the Turkish-Kurdish writer Burhan Sonmez, former president the Mexican novelist Jennifer Clement, and writers who had been imprisoned, like Uganda’s Stella Nyanzi, Myanmar’s Saw Wai and Ma Thida, Palestine’s Dareen Tatour, and Iran’s Fatemeh Ekhtesari, and other writers like the Paris-based Indian poet Karthika Nair, James Byrne in the UK, and the Australian writer Ali Cobby Eckermann, who are outraged by writers being forced into exile or being persecuted, besides many others, enthusiastically agreed to join. It so happened that 2021 was also PEN’s centenary year, which made this a particularly meaningful project. The PEN community is remarkable in its commitment to freedom to read and freedom to write, and everyone we reached out to, agreed to contribute a short piece or a poem.

This has been several years in the making, so I was doing it while engaged with PEN. It is my way of saying thank you to the PEN family for letting me be their spokesperson, and I cherish those friendships, as well as, most importantly, with Shilpa.

In your essay The Poet’s Work, you write about how words can “rouse us” and “trouble those with power”. Unfortunately, poets and authors who use words in this way have to pay a heavy price. What can individuals and civil society groups do to express support?

It is true that there are many cases of poets who speak out and challenge the powerful end up suffering. We know tragic stories like those of Osip Mandelstam, but also more recently the jail terms that Kim Chi Ha and Nâzım Hikmet have faced, and even more recently, Stella Nyanzi in Uganda and Varavara Rao in India. There are also unusual cases, like Majrooh Sultanpuri being jailed in Nehru’s India.

Not all the poems are aesthetically pleasing; some are intentionally disturbing; but for none of which should their readers or the writer suffer at the hands of the state. Readers can support the poets by reading them, buying their books, writing about them, writing to them in jail if they are imprisoned, reminding them that they are not forgotten, lobbying their own governments to seek their release, and calling upon their own governments to grant asylum to the writers who need it.

A large part of the proceeds from this book will go towards supporting PEN and other organisations committed to defending free speech, so I hope that spurs people to buy it. For readers in India, there are several reminders of what’s going on in India, with several original contributions (and in some cases previously published works) from Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, Varavara Rao, Umar Khalid, Karthika Nair, and Nilanjana Roy. And there is, of course, Shilpa’s exceptional original art.

You evoke poets across geographies – from Adrienne Rich to Ashok Vajpeyi, Liu Xiaobo to Nâzım Hikmet, Parul Khakhar to Mangesh Padgaonkar – while writing about freedom of expression. How do their words sustain your passion for working on human rights?

Adrienne Rich is one of Shilpa’s favourites, and she had alerted me to some of her writing about poetry, and I was outraged by Liu Xiaobo’s death. We both learned from writers we introduced to one another. Her team did an outstanding job tracking down the rights holders. All these writers – and there are many more in my essay – exemplify courage in its rawest form. They challenge the status quo; they speak for those whose voices are denied; they dream of a better tomorrow; they speak of love and equality and fairness and justice; they rage against injustice and brutality; and they satirise and ridicule the politician, the religious head, and the business tycoon, who wants to silence dissent. They tell the emperors that they have no clothes. There is an innocence in that provocative outburst, because it may seem naïve, but it is also very brave.

Human rights work can get very process-oriented, when it deals with specific elements of the law. But these writers remind us that the struggle for human rights isn’t a technical matter, but it is about preserving the beauty of what makes us who we are – of the human impulse which is at its base, of the heart beating beneath: and that raises my passion.

In a conversation with Sara Hossain, which is part of this anthology, you make a distinction between offense and harm. How would you explain it to people who are not familiar with the distinction? Could you share a few recent examples to make your point?

Thanks. Sara makes that distinction, and I agree with her. Sara says, “There’s a real distinction to be made between offence and harm. If there is a risk of harm, such that you’re inciting violence against particular individuals or communities, then clearly the criminal law has to step in. But in other instances, such as defamation, there should only be civil action, for seeking damages. Using the criminal law is completely unconscionable in these cases.”

The distinction isn’t legal sophistry; she is absolutely right. Offence is what people claim when they say they are offended. It is subjective. But harm is specific and measurable; it is what people experience, often in the form of violence. If I say “X is stupid,” it may be offensive to X, whether X is an individual or a group. If I say “X is stupid and should be beaten up or killed,” and if that incites violence, it causes real harm and the law restricts such speech – legitimately so – in many jurisdictions. The former can be ignored as the rant of an individual; the latter is what my friend, the American academic Susan Benesch calls “dangerous speech”, especially if it is made by someone in a power to influence outcomes, speaking to a crowd that’s already incited.

When a drunkard outside a pub calls people of a particular religion bigots who should be “sent back to where they belong,” it is offensive but it should be and can be ignored; when a public official calls refugees “termites,” or the sole radio station calls a minority “cockroaches,” that is far more problematic because it can, and often has, led to genocide.

To return to our persecuted poets – they have their pens, pencils, keyboards; they have their imagination and courage; and they have the boldness to believe that their words can turn the tide. We must listen to those voices.

You refer to Salman Rushdie in this anthology and in your untitled poem that begins with ‘This we have learned’ in PEN’s India at 75 anthology. How would you describe your association with him? How has he influenced your thinking about freedom of expression?

Rushdie has been the most important standard-bearer in the battle of free speech. He lives free speech. He has provided so much clarity about how to think about the great issues: that you challenge faith with doubt, for that’s where reason begins. He has made us believe that we can own the language, and we are limited only by our imagination. He is easily one of the greatest writers of the last century, and indeed of all time. What he has done to the language, to the richness of imagination, to help establish connections between diverse story threads, and by revealing the world in its complexities, is immense and immeasurable. He helps us understand our post-colonial, hybridized, post-modern world as perhaps no other writer in our time has done.

When we (Kiran Desai, Suketu Mehta, and myself, and the three of us are members of PEN America) reached out to writers for the PEN anthology, Rushdie was the first to respond with a powerful paragraph about what has become of India at 75. It helped set the tone of what was to follow, and clearly, our call spurred many writers, who had wanted to speak out, to use the opportunity, and eventually we had more than 100 writers contributing to the anthology.

I have known Rushdie since 1983, when I first interviewed him soon after Midnight’s Children won the Booker and he was on his first trip back to India since that honour. It has been my privilege to have interviewed him, or had live or recorded conversations with him consistently since then, on themes including his writing and the state of our world. He has a great sense of humour, an incredible empathy for other writers at risk, he is ever willing to help writers facing persecution, and he is steadfast in his commitment to freedom of expression; all of which have deeply influenced me. I am sure everyone joins me in wishing him a healing, speedy recovery.

In the poem My Mother’s Fault, you write, “I live abroad: what do I know of India?” How do you feel when your relationship with and knowledge of India is questioned? Does living abroad let you comment on Indian politics with some degree of protection from backlash?

People do question me, asking exactly that: what do I know of India, if I don’t live there? They do have the right to question me. But some among them speak with preconceived assumptions and perceptions, (which too is their right, but doesn’t make them right!) I ignore many such attacks, because they emerge out of ignorance and are often personal. India is too complex for anyone to claim intimate awareness of it, and it is too big and strong to be weakened by a writer questioning its direction. But it is laughable to argue that merely because someone lives in another country, they lose the right to speak about India, or that they don’t know India. Much of such backlash is online, and except for a few instances where people have made serious threats (or found out my email address and written in a language that their parents would have scolded them for), most attacks I get are poorly-spelt, hilarious, and attempt adolescent humour, such as trying to body shame me or imply that I am an idiot. Again, they have the right to say ridiculous things, as I have the right to avoid them from distracting me from what I want to do.

I am not sure if living abroad is special however, but the distance helps me see issues in perspective – where the behaviour of some powerful people is grotesque and outrageous, and where some incidents are relatively insignificant in the grand scheme of things. I also appreciate that living abroad is my choice, and I salute those who are fighting the more crucial and important battles within – in India as well as in other countries.

When the India at 75 anthology was critiqued for over-representation of savarna, especially Brahmin voices, you commented by saying, “Excellent statistical analysis of people’s ethnicities, if true. I’m sure you’d have a great job in Germany in the 1930s.” What made you draw parallels between people questioning caste hierarchies and Nazis? If you could go back in time, and respond differently to the critique, what would you say?

I would like the anthology to speak for itself.

Your previous books Offence: The Hindu Case (2009), The Colonel Who Would Not Repent (2014) and Detours: Songs of the Open Road (2015) are so different from each other in subject and style. How did you develop this astounding range as a writer?

Each book emerged in its time, as a specific response to what I felt strongly. Offence was at the invitation of Judith Vidal-Hall of Index on Censorship and Naveen Kishore of Seagull Books, as part of a series on religious intolerance and free speech, and mine was a commentary on rising Hindu nationalism. (Other books dealt with other religions in that series). It was written in 2007 and 2008. Given what has become of India, I am now amused when I read a couple of reviews which came out at that time, which said my prognosis was needlessly alarmist. The Colonel is my response to Bangladesh – the one war I have conscious memory of, and my subsequent work in human rights, and my desire to learn about mass cruelty and atrocities, and the idea of justice, as well as my deep love for Bengali language and culture. I had chosen to learn Bengali in my teens and can understand it well and read it, and I do speak it, though hesitantly. And Detours is in a sense autobiographical – my sons at least think so – in that it tells stories about life, love, and art, through travel of places I’ve been. There are three perspectives – war and tragedies; writers and art; and love and loss. The first part deals with places like Colombia, Cambodia, and Nigeria; the second, with places that inspired writers like Hemingway; and the third is an attempt to recreate my past, by revisiting places I had once gone with my late wife Karuna, who died in 2006. So, while outwardly unrelated, I’d think there is a connecting thread, of me as a witness trying to understand our world.

Could you give us a peek into what your much-awaited book The Gujaratis is all about?

There will be time to talk about the book soon, I promise!

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.

How did you and artist Shilpa Gupta end up working together on this anthology? What skills, expertise, and institutional resources did each of you bring to this book project?

In February 2017 at a dinner at Kekee Manzil, the delightful home of my good friend Shireen Gandhy of the Chemould Prescott Road Gallery in Bombay, Shireen introduced me to Shilpa. She had told Shilpa about my book The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and Its Unquiet Legacy (2014), and was keen that we meet since Shilpa had made three shows around the Indo-Bangladesh borderland.

We met at Shilpa’s studio again a few days later and spoke of the many common areas of interest. Since then, it has been a privilege and honour for me to work with someone as gifted and committed as Shilpa. She probed deeply about my writing, read all my books, and I saw more of her art at her studio over several visits and at a few shows.

We also realised we were both at the National Gallery of Modern Art at its opening in 1997 in Bombay, when there was a show on the Progressive Artists; I was mingling with artists and she was among the JJ School of Art students with a banner that said “Husain, we miss you”. MF Husain had left Bombay to live in self-imposed exile at that time because he was a victim of ceaseless, frivolous persecution in India. That scene opens my first book Offence: The Hindu Case (2009) though I had not known Shilpa then.

Shilpa started getting my articles on a mailing list I maintain, and send to friends who’d like to read what I write. One such email was a speech I gave in Bombay in April 2017. It was to mark the silver jubilee of Abhidhanantar – the Marathi journal that the poet and publisher Hemant Divate publishes – and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences had organised a poetry festival on its Bombay campus with leading Indian poets, including Jayanta Mahapatra, Manglesh Dabral, and many other stalwarts. Ashwani Kumar was the magnet that attracted us.

I was invited to give a keynote address, where I spoke about the role of a poet as a dissident, as the one who protests, and who also suffers. This was at the time when poets, writers and artists were returning national awards in India because of their anger over state inaction in the face of rising intolerance. In my address, I recounted examples over hundreds of years, of poets around the world, who had been jailed or killed, but who persisted.

Shilpa liked that speech. She has worked for years on politically charged and challenging themes, including the borders in our minds and on the frontier, censorship of books, the impossibility of telling if a bottle of blood belongs to one faith or another, and other provocative displays of public art that force us to think. These are the themes that move me too.

She had written a proposal for a sound installation project based on voices of one hundred writers from an earlier installation piece of hers from 2011 – called Someone Else – of 100 books written anonymously or under pseudonyms as many of the writers had faced censorship. But my speech made Shilpa take a “detour”, as she puts it to me; she began a deep dive, researching ceaselessly on poets who had been imprisoned. She came across many moving stories, including many I had not mentioned and some I wasn’t aware of, and that made her want to share such stories from the past and present.

In a little over a year, she had conceptualised this astonishingly powerful sound installation – For In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit where you see, in a dimly lit room, spikes pierce through sheets of paper on which there are fragments of poems. The black microphones hanging from the ceiling don’t amplify your voice, but you hear the soft voices in many languages, murmurs of persecuted poets, haunting you.

She first showed the installation in Baku, and later in Brisbane, the Edinburgh Art Festival, Venice Biennale, Kochi Biennale, the Barbican in London, and the Dallas Contemporary. I joined her in Edinburgh and Kochi, where we spoke about the work, what inspired her, and what had drawn me to the poets, and how our collaboration happened. She wanted the installation to stay vivid, and so the idea of the book came about. We would use extracts of poems from the majority of the poets in the installation, and seek out essays, poems, or conversations with writers from around the world, who were either persecuted themselves, or knew those who were persecuted, or were moved by their stories to write.

How did your experience of chairing PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and co-chairing English PEN’s Writers at Risk Committee shape this anthology?

Immensely! I could not have done it without having been engaged with PEN. I had co-chaired the Writers at Risk Committee in the UK with my friend, the novelist Kamila Shamsie, and from 2015 to 2021 I chaired the Writers in Prison Committee internationally. Both those stints reminded me daily of the writers and poets who are in jail only for expressing their views that those in power don’t like. Sara Whyatt, a senior researcher who has worked with PEN, built on the hours of research Shilpa and her team had put together on each poet, and she wrote the biographical entries. Other writers who are PEN members, including current president, the Turkish-Kurdish writer Burhan Sonmez, former president the Mexican novelist Jennifer Clement, and writers who had been imprisoned, like Uganda’s Stella Nyanzi, Myanmar’s Saw Wai and Ma Thida, Palestine’s Dareen Tatour, and Iran’s Fatemeh Ekhtesari, and other writers like the Paris-based Indian poet Karthika Nair, James Byrne in the UK, and the Australian writer Ali Cobby Eckermann, who are outraged by writers being forced into exile or being persecuted, besides many others, enthusiastically agreed to join. It so happened that 2021 was also PEN’s centenary year, which made this a particularly meaningful project. The PEN community is remarkable in its commitment to freedom to read and freedom to write, and everyone we reached out to, agreed to contribute a short piece or a poem.

This has been several years in the making, so I was doing it while engaged with PEN. It is my way of saying thank you to the PEN family for letting me be their spokesperson, and I cherish those friendships, as well as, most importantly, with Shilpa.

In your essay The Poet’s Work, you write about how words can “rouse us” and “trouble those with power”. Unfortunately, poets and authors who use words in this way have to pay a heavy price. What can individuals and civil society groups do to express support?

It is true that there are many cases of poets who speak out and challenge the powerful end up suffering. We know tragic stories like those of Osip Mandelstam, but also more recently the jail terms that Kim Chi Ha and Nâzım Hikmet have faced, and even more recently, Stella Nyanzi in Uganda and Varavara Rao in India. There are also unusual cases, like Majrooh Sultanpuri being jailed in Nehru’s India.

Not all the poems are aesthetically pleasing; some are intentionally disturbing; but for none of which should their readers or the writer suffer at the hands of the state. Readers can support the poets by reading them, buying their books, writing about them, writing to them in jail if they are imprisoned, reminding them that they are not forgotten, lobbying their own governments to seek their release, and calling upon their own governments to grant asylum to the writers who need it.

A large part of the proceeds from this book will go towards supporting PEN and other organisations committed to defending free speech, so I hope that spurs people to buy it. For readers in India, there are several reminders of what’s going on in India, with several original contributions (and in some cases previously published works) from Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, Varavara Rao, Umar Khalid, Karthika Nair, and Nilanjana Roy. And there is, of course, Shilpa’s exceptional original art.

You evoke poets across geographies – from Adrienne Rich to Ashok Vajpeyi, Liu Xiaobo to Nâzım Hikmet, Parul Khakhar to Mangesh Padgaonkar – while writing about freedom of expression. How do their words sustain your passion for working on human rights?

Adrienne Rich is one of Shilpa’s favourites, and she had alerted me to some of her writing about poetry, and I was outraged by Liu Xiaobo’s death. We both learned from writers we introduced to one another. Her team did an outstanding job tracking down the rights holders. All these writers – and there are many more in my essay – exemplify courage in its rawest form. They challenge the status quo; they speak for those whose voices are denied; they dream of a better tomorrow; they speak of love and equality and fairness and justice; they rage against injustice and brutality; and they satirise and ridicule the politician, the religious head, and the business tycoon, who wants to silence dissent. They tell the emperors that they have no clothes. There is an innocence in that provocative outburst, because it may seem naïve, but it is also very brave.

Human rights work can get very process-oriented, when it deals with specific elements of the law. But these writers remind us that the struggle for human rights isn’t a technical matter, but it is about preserving the beauty of what makes us who we are – of the human impulse which is at its base, of the heart beating beneath: and that raises my passion.

In a conversation with Sara Hossain, which is part of this anthology, you make a distinction between offense and harm. How would you explain it to people who are not familiar with the distinction? Could you share a few recent examples to make your point?

Thanks. Sara makes that distinction, and I agree with her. Sara says, “There’s a real distinction to be made between offence and harm. If there is a risk of harm, such that you’re inciting violence against particular individuals or communities, then clearly the criminal law has to step in. But in other instances, such as defamation, there should only be civil action, for seeking damages. Using the criminal law is completely unconscionable in these cases.”

The distinction isn’t legal sophistry; she is absolutely right. Offence is what people claim when they say they are offended. It is subjective. But harm is specific and measurable; it is what people experience, often in the form of violence. If I say “X is stupid,” it may be offensive to X, whether X is an individual or a group. If I say “X is stupid and should be beaten up or killed,” and if that incites violence, it causes real harm and the law restricts such speech – legitimately so – in many jurisdictions. The former can be ignored as the rant of an individual; the latter is what my friend, the American academic Susan Benesch calls “dangerous speech”, especially if it is made by someone in a power to influence outcomes, speaking to a crowd that’s already incited.

When a drunkard outside a pub calls people of a particular religion bigots who should be “sent back to where they belong,” it is offensive but it should be and can be ignored; when a public official calls refugees “termites,” or the sole radio station calls a minority “cockroaches,” that is far more problematic because it can, and often has, led to genocide.

To return to our persecuted poets – they have their pens, pencils, keyboards; they have their imagination and courage; and they have the boldness to believe that their words can turn the tide. We must listen to those voices.

You refer to Salman Rushdie in this anthology and in your untitled poem that begins with ‘This we have learned’ in PEN’s India at 75 anthology. How would you describe your association with him? How has he influenced your thinking about freedom of expression?

Rushdie has been the most important standard-bearer in the battle of free speech. He lives free speech. He has provided so much clarity about how to think about the great issues: that you challenge faith with doubt, for that’s where reason begins. He has made us believe that we can own the language, and we are limited only by our imagination. He is easily one of the greatest writers of the last century, and indeed of all time. What he has done to the language, to the richness of imagination, to help establish connections between diverse story threads, and by revealing the world in its complexities, is immense and immeasurable. He helps us understand our post-colonial, hybridized, post-modern world as perhaps no other writer in our time has done.

When we (Kiran Desai, Suketu Mehta, and myself, and the three of us are members of PEN America) reached out to writers for the PEN anthology, Rushdie was the first to respond with a powerful paragraph about what has become of India at 75. It helped set the tone of what was to follow, and clearly, our call spurred many writers, who had wanted to speak out, to use the opportunity, and eventually we had more than 100 writers contributing to the anthology.

I have known Rushdie since 1983, when I first interviewed him soon after Midnight’s Children won the Booker and he was on his first trip back to India since that honour. It has been my privilege to have interviewed him, or had live or recorded conversations with him consistently since then, on themes including his writing and the state of our world. He has a great sense of humour, an incredible empathy for other writers at risk, he is ever willing to help writers facing persecution, and he is steadfast in his commitment to freedom of expression; all of which have deeply influenced me. I am sure everyone joins me in wishing him a healing, speedy recovery.

In the poem My Mother’s Fault, you write, “I live abroad: what do I know of India?” How do you feel when your relationship with and knowledge of India is questioned? Does living abroad let you comment on Indian politics with some degree of protection from backlash?

People do question me, asking exactly that: what do I know of India, if I don’t live there? They do have the right to question me. But some among them speak with preconceived assumptions and perceptions, (which too is their right, but doesn’t make them right!) I ignore many such attacks, because they emerge out of ignorance and are often personal. India is too complex for anyone to claim intimate awareness of it, and it is too big and strong to be weakened by a writer questioning its direction. But it is laughable to argue that merely because someone lives in another country, they lose the right to speak about India, or that they don’t know India. Much of such backlash is online, and except for a few instances where people have made serious threats (or found out my email address and written in a language that their parents would have scolded them for), most attacks I get are poorly-spelt, hilarious, and attempt adolescent humour, such as trying to body shame me or imply that I am an idiot. Again, they have the right to say ridiculous things, as I have the right to avoid them from distracting me from what I want to do.

I am not sure if living abroad is special however, but the distance helps me see issues in perspective – where the behaviour of some powerful people is grotesque and outrageous, and where some incidents are relatively insignificant in the grand scheme of things. I also appreciate that living abroad is my choice, and I salute those who are fighting the more crucial and important battles within – in India as well as in other countries.

When the India at 75 anthology was critiqued for over-representation of savarna, especially Brahmin voices, you commented by saying, “Excellent statistical analysis of people’s ethnicities, if true. I’m sure you’d have a great job in Germany in the 1930s.” What made you draw parallels between people questioning caste hierarchies and Nazis? If you could go back in time, and respond differently to the critique, what would you say?

I would like the anthology to speak for itself.

Your previous books Offence: The Hindu Case (2009), The Colonel Who Would Not Repent (2014) and Detours: Songs of the Open Road (2015) are so different from each other in subject and style. How did you develop this astounding range as a writer?

Each book emerged in its time, as a specific response to what I felt strongly. Offence was at the invitation of Judith Vidal-Hall of Index on Censorship and Naveen Kishore of Seagull Books, as part of a series on religious intolerance and free speech, and mine was a commentary on rising Hindu nationalism. (Other books dealt with other religions in that series). It was written in 2007 and 2008. Given what has become of India, I am now amused when I read a couple of reviews which came out at that time, which said my prognosis was needlessly alarmist. The Colonel is my response to Bangladesh – the one war I have conscious memory of, and my subsequent work in human rights, and my desire to learn about mass cruelty and atrocities, and the idea of justice, as well as my deep love for Bengali language and culture. I had chosen to learn Bengali in my teens and can understand it well and read it, and I do speak it, though hesitantly. And Detours is in a sense autobiographical – my sons at least think so – in that it tells stories about life, love, and art, through travel of places I’ve been. There are three perspectives – war and tragedies; writers and art; and love and loss. The first part deals with places like Colombia, Cambodia, and Nigeria; the second, with places that inspired writers like Hemingway; and the third is an attempt to recreate my past, by revisiting places I had once gone with my late wife Karuna, who died in 2006. So, while outwardly unrelated, I’d think there is a connecting thread, of me as a witness trying to understand our world.

Could you give us a peek into what your much-awaited book The Gujaratis is all about?

There will be time to talk about the book soon, I promise!

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.