Shehan Karunatilaka – “Writing a queer novel was never my intention”

Did Maali Almeida – the protagonist of your novel – start off as a closeted gay man in your imagination, or did you add this detail while developing the character?

Well, the initial inspiration for the character of Maali Almeida came from the real-life story of a Sri Lankan man called Richard de Zoysa. He was a newsreader, actor, poet and activist. When he was abducted and killed in 1990, that incident really shook up the Colombo bubble. Several activists and journalists from Sri Lanka had been murdered before that but the outrage that this particular killing led to was unprecedented and quite widespread. People began to think that if Richard could be killed, the powers that be could come after anyone.

After his body was found, different theories were floating around regarding who planned and executed his death, and also whether he was affiliated to the militant organisation Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna or not. As I developed the character, many details changed. Richard was neither a war photographer nor a gambler but Maali fits both these descriptions. What Maali does have in common with Richard is the fact that he too is a closeted gay man.

It is widely known now that Richard was leading a double life, had a stash of photographs hidden under his bed, and was secretly having sex with men. All of this stayed with me, and I used these details while conceptualizing and writing the character of Maali in my novel.

How has your representation of a closeted gay man been received by the LGBTQIA+ community in Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan diaspora?

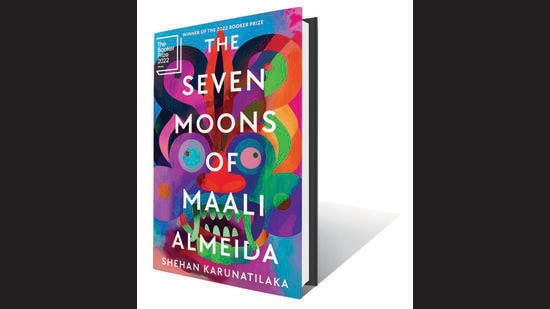

To be honest, I do not know about their reactions to The Seven Moons of Almeida. Someone at the Jaipur Literature Festival called it a work of queer literature but I have my doubts about whether it deserves to be seen as one. The truth is that I may not be brave enough to try my hand at queer literature. I was merely exploring the life of this character in my book. That said, my research did involve speaking to gay men who were Richard’s contemporaries and younger gay guys in today’s Sri Lanka who use Grindr to meet. I gave them parts of the book to read to make sure that I was not being offensive and the character was not ill-conceived. On the one hand, the promiscuous gay is a stereotype. On the other hand, promiscuity is also one of many realities among gay men in Sri Lanka and elsewhere.

Tell us about the gay rights scenario in Sri Lanka, and whether you think that The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida might contribute in some way to that conversation.

I do not think we have much of a conversation around gay rights in Sri Lanka but this needs to change. What is worth mentioning is the role of the “Aragalaya” in uniting Sri Lankans across divides. In Sri Lanka, we generally use the term “Aragalaya” – which literally means “struggle” – for the mass protests of March 2022 that led to the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Protestors occupied his house, and he eventually fled the country.

Attending those protests was a heady experience because we saw Sri Lankans of different generations, races, sexual orientations come together. We also had a Pride parade on the streets, which is a totally different ball game from Pride parties in night clubs. While I do not think of Sri Lankan society as particularly homophobic, it is clear that no political party is ready to take up the issue of gay rights. They are occupied with socio-economic issues, and they think that homosexuality is not really a part of our culture so we do not need to bother.

That said, being an out gay man is probably much easier in Colombo than other parts of Sri Lanka. It is hard for me to say if my book will contribute in any significant way as far as closeted gay men are concerned but I have been hearing criticism from people who believe that I decided to write about a closeted gay character to pander to literary critics in the West. Frankly, I do not have a rejoinder to offer to this kind of a backlash because writing a queer novel was never my intention. I really just went with my instinct with Maali Almeida.

This novel and your book of short stories, The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises (2022), hint at your fascination with the afterlife. Does this have to do with growing up in a Buddhist family, or in a country where so many deaths are still unaccounted for?

This is a really interesting question, and I would love to answer it. I did some ghost hunting but I did not see much. What I found utterly captivating was the work of Sasanka Perera, a Sri Lankan anthropologist who lives and teaches in Delhi. His research shows that wherever there is trauma related to massacres, there are ghost stories. In some cases, the trauma is related to the civil war or mass abduction and killings. In other cases, the trauma comes from villages being ravaged by a natural disaster like the tsunami. There are records of people in these areas narrating stories about seeing apparitions coming out of the sea. I got curious about this idea of restless souls wandering around and looking for closure while the living did not care much to hear their voices or push for pending murder investigations to be resolved.

What role has religion played in feeding your imagination of the afterlife?

I am a Sinhala Buddhist – a majoritarian oppressor in the context of Sri Lanka. Going to temples and participating in rituals was definitely a part of my childhood. When I was older, I went to an Anglican school in New Zealand. My grandmother is Christian, and so is my wife. Quite early in life, I had the impression that the wise guy in the robe that you are supposed to listen to is not all that wise. I do have a meditation app on my phone. I am interested in mindfulness. But as far as a religious identity is concerned, I am just nominally a Buddhist.

Haven’t the hungry ghosts described in Buddhist literature informed your writing?

Oh, yes, of course they have! I encountered this aspect of Buddhism when I lived in Singapore, where people strongly believe in hungry ghosts, and also have a hungry ghost festival. My travels to Ladakh and Sikkim brought me into deeper contact with Mahayana Buddhism, which is quite different from the Theravada Buddhism that I grew up with. The pantheon of deities, and the storytelling in Mahayana, is far more interesting to me. I borrowed some elements from there. Apart from that, I am also interested in near-death experiences especially because of that trope of wandering into the light and waking up and hovering above your own body. I have taken from all these sources. I have read philosophers and religious people. I have watched horror movies. I have read up on rebirth in eastern religions. The research process can be incredibly exciting if you like to learn new things.

At the Jaipur Literature Festival, you pointed out that many of the characters you have created have daddy issues. What, according to you, might be the reason behind this?

(laughs) My dad was a gynaecologist with a traditional Sinhala Buddhist upbringing. He wanted me to be an accountant or an economist. I don’t think that I have any big trauma but ours was a typical father-son relationship that would be familiar to many other guys from my generation. I did not get a lot of hugs from him but we would bond over cricket. I think it was a bit like this: “I didn’t leave your mother. What more do you want from me as a father?” My friends had similar experiences with their fathers. Today, fathers are much more hands-on.

Going back to my fiction, well, your question reminds me of my book Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Matthew (2010). It is a novel about cricket but also about a father and a son connecting with each other. This might sound funny now but I think it was during the 1996 Cricket World Cup that the three males in our family – my father, my little brother Lalith, and I – talked the most. That used to be the predominant code of interaction. Now we talk about different kinds of masculinity, and try to communicate in different ways. I suppose this is what I had on my mind when I spoke about daddy issues in my novels and stories.

You are a dad who also writes children’s books…

Yes, I have a daughter and a son. The challenges of parenting make me come up with ideas for children’s books. I enjoyed writing Please Don’t Put That in Your Mouth (2019) and Where Shall I Poop? (2022). My brother Lalith illustrated them. My next book for children is about sleep. When I was in my 20s, I hardly cared about getting enough sleep but now in my 40s, I try to get at least seven to eight hours of sound sleep every day. I have also been working on a children’s book about insects. I would like to do two every year. Let’s see.

Did your father read out stories to you at bedtime?

No, he didn’t but my mother certainly did! I usually like reading aloud to my children if they are not too naughty. In fact, that time with them is sometimes the best part of my entire day.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.

Did Maali Almeida – the protagonist of your novel – start off as a closeted gay man in your imagination, or did you add this detail while developing the character?

Well, the initial inspiration for the character of Maali Almeida came from the real-life story of a Sri Lankan man called Richard de Zoysa. He was a newsreader, actor, poet and activist. When he was abducted and killed in 1990, that incident really shook up the Colombo bubble. Several activists and journalists from Sri Lanka had been murdered before that but the outrage that this particular killing led to was unprecedented and quite widespread. People began to think that if Richard could be killed, the powers that be could come after anyone.

After his body was found, different theories were floating around regarding who planned and executed his death, and also whether he was affiliated to the militant organisation Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna or not. As I developed the character, many details changed. Richard was neither a war photographer nor a gambler but Maali fits both these descriptions. What Maali does have in common with Richard is the fact that he too is a closeted gay man.

It is widely known now that Richard was leading a double life, had a stash of photographs hidden under his bed, and was secretly having sex with men. All of this stayed with me, and I used these details while conceptualizing and writing the character of Maali in my novel.

How has your representation of a closeted gay man been received by the LGBTQIA+ community in Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan diaspora?

To be honest, I do not know about their reactions to The Seven Moons of Almeida. Someone at the Jaipur Literature Festival called it a work of queer literature but I have my doubts about whether it deserves to be seen as one. The truth is that I may not be brave enough to try my hand at queer literature. I was merely exploring the life of this character in my book. That said, my research did involve speaking to gay men who were Richard’s contemporaries and younger gay guys in today’s Sri Lanka who use Grindr to meet. I gave them parts of the book to read to make sure that I was not being offensive and the character was not ill-conceived. On the one hand, the promiscuous gay is a stereotype. On the other hand, promiscuity is also one of many realities among gay men in Sri Lanka and elsewhere.

Tell us about the gay rights scenario in Sri Lanka, and whether you think that The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida might contribute in some way to that conversation.

I do not think we have much of a conversation around gay rights in Sri Lanka but this needs to change. What is worth mentioning is the role of the “Aragalaya” in uniting Sri Lankans across divides. In Sri Lanka, we generally use the term “Aragalaya” – which literally means “struggle” – for the mass protests of March 2022 that led to the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Protestors occupied his house, and he eventually fled the country.

Attending those protests was a heady experience because we saw Sri Lankans of different generations, races, sexual orientations come together. We also had a Pride parade on the streets, which is a totally different ball game from Pride parties in night clubs. While I do not think of Sri Lankan society as particularly homophobic, it is clear that no political party is ready to take up the issue of gay rights. They are occupied with socio-economic issues, and they think that homosexuality is not really a part of our culture so we do not need to bother.

That said, being an out gay man is probably much easier in Colombo than other parts of Sri Lanka. It is hard for me to say if my book will contribute in any significant way as far as closeted gay men are concerned but I have been hearing criticism from people who believe that I decided to write about a closeted gay character to pander to literary critics in the West. Frankly, I do not have a rejoinder to offer to this kind of a backlash because writing a queer novel was never my intention. I really just went with my instinct with Maali Almeida.

This novel and your book of short stories, The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises (2022), hint at your fascination with the afterlife. Does this have to do with growing up in a Buddhist family, or in a country where so many deaths are still unaccounted for?

This is a really interesting question, and I would love to answer it. I did some ghost hunting but I did not see much. What I found utterly captivating was the work of Sasanka Perera, a Sri Lankan anthropologist who lives and teaches in Delhi. His research shows that wherever there is trauma related to massacres, there are ghost stories. In some cases, the trauma is related to the civil war or mass abduction and killings. In other cases, the trauma comes from villages being ravaged by a natural disaster like the tsunami. There are records of people in these areas narrating stories about seeing apparitions coming out of the sea. I got curious about this idea of restless souls wandering around and looking for closure while the living did not care much to hear their voices or push for pending murder investigations to be resolved.

What role has religion played in feeding your imagination of the afterlife?

I am a Sinhala Buddhist – a majoritarian oppressor in the context of Sri Lanka. Going to temples and participating in rituals was definitely a part of my childhood. When I was older, I went to an Anglican school in New Zealand. My grandmother is Christian, and so is my wife. Quite early in life, I had the impression that the wise guy in the robe that you are supposed to listen to is not all that wise. I do have a meditation app on my phone. I am interested in mindfulness. But as far as a religious identity is concerned, I am just nominally a Buddhist.

Haven’t the hungry ghosts described in Buddhist literature informed your writing?

Oh, yes, of course they have! I encountered this aspect of Buddhism when I lived in Singapore, where people strongly believe in hungry ghosts, and also have a hungry ghost festival. My travels to Ladakh and Sikkim brought me into deeper contact with Mahayana Buddhism, which is quite different from the Theravada Buddhism that I grew up with. The pantheon of deities, and the storytelling in Mahayana, is far more interesting to me. I borrowed some elements from there. Apart from that, I am also interested in near-death experiences especially because of that trope of wandering into the light and waking up and hovering above your own body. I have taken from all these sources. I have read philosophers and religious people. I have watched horror movies. I have read up on rebirth in eastern religions. The research process can be incredibly exciting if you like to learn new things.

At the Jaipur Literature Festival, you pointed out that many of the characters you have created have daddy issues. What, according to you, might be the reason behind this?

(laughs) My dad was a gynaecologist with a traditional Sinhala Buddhist upbringing. He wanted me to be an accountant or an economist. I don’t think that I have any big trauma but ours was a typical father-son relationship that would be familiar to many other guys from my generation. I did not get a lot of hugs from him but we would bond over cricket. I think it was a bit like this: “I didn’t leave your mother. What more do you want from me as a father?” My friends had similar experiences with their fathers. Today, fathers are much more hands-on.

Going back to my fiction, well, your question reminds me of my book Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Matthew (2010). It is a novel about cricket but also about a father and a son connecting with each other. This might sound funny now but I think it was during the 1996 Cricket World Cup that the three males in our family – my father, my little brother Lalith, and I – talked the most. That used to be the predominant code of interaction. Now we talk about different kinds of masculinity, and try to communicate in different ways. I suppose this is what I had on my mind when I spoke about daddy issues in my novels and stories.

You are a dad who also writes children’s books…

Yes, I have a daughter and a son. The challenges of parenting make me come up with ideas for children’s books. I enjoyed writing Please Don’t Put That in Your Mouth (2019) and Where Shall I Poop? (2022). My brother Lalith illustrated them. My next book for children is about sleep. When I was in my 20s, I hardly cared about getting enough sleep but now in my 40s, I try to get at least seven to eight hours of sound sleep every day. I have also been working on a children’s book about insects. I would like to do two every year. Let’s see.

Did your father read out stories to you at bedtime?

No, he didn’t but my mother certainly did! I usually like reading aloud to my children if they are not too naughty. In fact, that time with them is sometimes the best part of my entire day.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.