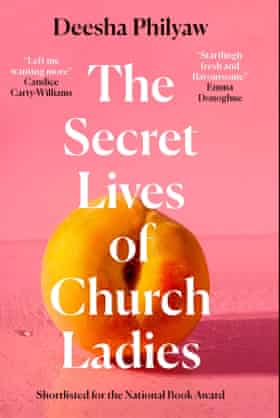

Short story writer Deesha Philyaw: ‘I wanted to challenge the church’s obsession with sex’ | Books

When asked to choose their favourite story in The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, Deesha Philyaw’s acclaimed debut collection, most people, the author tells me, say Peach Cobbler. This simultaneously funny and punch-in-the-guts-devastating tale focuses on Olivia, a young girl in the American south who believes the local pastor to be God, because when he visits she overhears her mother screaming “Oh, God!” from the bedroom.

Central to the story is the “best cobbler in the world” – a fruit pie that Olivia’s mother bakes for her lover each week, but which Olivia is forbidden from tasting. Philyaw set out, she tells me from her home in Pennsylvania, to write about “the Blackest dessert”, and peach cobbler came to mind. “In fact, the Blackest dessert is not peach cobbler, it’s pound cake,” she remarks in retrospect. “But I think my brain knew that there was more to peach cobbler than just the Blackness – there’s the textures, the sweetness, the sensuality of it.”

Whatever she was writing, the 50-year-old from Jacksonville, Florida kept coming back to her childhood and the “secret lives” of the women she knew then. Having been sent to church from a young age by her mother and grandmother (who did not attend church themselves), Philyaw had always been curious about the southern Black women around her and how they navigated the “rules” set by the church. “Early on, we were taught that sex was an absolute no, and that anything that happened to you sexually was your fault,” she remembers. As she grew older and started to experiment sexually herself, she continued to wonder about the other women in church: “Did they think sex was bad? Did they like it? Did they masturbate? And how did they grapple with these questions?”

The characters in Church Ladies, which has picked up a National Book Award nomination and won the PEN/Faulkner award, the LA Times book prize and The Story Prize in the US prior to its UK release this week, respond in different ways. There’s Eula, who insists on “saving herself” for marriage to a man, but happily celebrates her birthday each year by having sex with her female best friend; there’s an unnamed bakery owner, implied to be an older Olivia from Peach Cobbler, who provides married men with a set of instructions before they begin an affair with her; and there’s Lyra, who is forced to address the shame she feels around sex when she falls in love at the age of 42.

Philyaw and I are speaking over video call: me in London, mortified to find I’ve got the writer up at 6am; her in Pittsburgh, serene and cheerful, insisting that she is usually awake at this time anyway. She hadn’t always wanted to be a writer, I learn. As a first-generation university student, Philyaw was “aiming to go to college and do something practical and make a lot of money”. If she’d told her family she had literary ambitions, she says, “I might as well have said I want to be Michael Jackson”.

So she went to Yale, got a degree in economics, and initially worked as a management consultant (“I cried every day for months”) before retraining as a teacher, a job she “absolutely loved”. But when Philyaw and her then-husband decided to have children, she gave up teaching to stay at home with her eldest daughter, and started writing “just to do something that was stimulating for myself”. In 2005 she tentatively decided to try to make a living from her hobby.

While she was trying to write a novel, her first published book was a co-parenting guide that she wrote with her ex-husband, a project that came about almost by accident. Friends had dubbed the pair the “poster children for divorce” because of the way they handled their parenting responsibilities after separating, and the book grew from there. Writing Co-Parenting 101 landed Philyaw an agent, bringing her dream of having a novel published one step closer.

It was during a break from the difficult work of novel writing that Church Ladies started to come together. Philyaw had written short fiction in response to competitions and call-outs and hadn’t noticed that her stories tended to share a common theme. It was only when her agent started to refer to them as “church lady stories” that she realised she had been subconsciously zooming in on the questions of her childhood.

The resulting collection is so astute on the particular kind of sexual shame that strict religious teaching can cause that I’m surprised when Philyaw tells me she “didn’t have that kind of baggage” herself. While she attended church until the age of 35, she never felt fully subscribed to Christianity or beholden to its rules. When her mother, father and grandmother all died in the same year, she stopped going altogether – not because she was angry at God, but because she felt nothing there at all. “Why am I getting up on Sunday mornings, the one morning that I can sleep in?” she asked herself. “Because I’m not getting anything out of this.”

Fifteen years later, she is able to reflect on why the church stigmatises sex so much. It comes down to the Black American Christian community’s roots in slavery, she believes. “Slavery was justified, in part, by saying that we weren’t human, and that Black women in particular were promiscuous and hypersexual.” So after emancipation, when churches became cornerstone institutions for the Black community, the response was often: “We’re going to be the opposite of that: we’re going to be pure and we’re going to be blameless, and we’re going to conduct ourselves with propriety.”

This attitude has led to the decades of generational shame that Philyaw has been observing all her life – but the writer doesn’t want to entirely condemn Christianity. Her hope was that Church Ladies would challenge the church’s misogyny and “obsession with sex”, without demonising the institution altogether. Similarly, she has tried not to make villains out of the men in her stories. In fact, although the impact of a wider misogynistic culture is certainly felt, men don’t actually appear much. Philyaw thinks her friend Damon Young, an early reader of the book, describes it best. “He said, the men in this book are like garnish: they’re on the plate, but they’re not the meal. And I thought, that’s it. I definitely wanted to keep the women centred, but I certainly wasn’t trying to thumb my nose at the men.”

The absence of men, particularly of father figures, is perhaps reflective of Philyaw’s own experience. Although none of the stories is directly based on the author’s life, she admits there are “kernels” of herself in there, and that “one of the biggest kernels is in the story Dear Sister”. Like Nichelle, the protagonist of the epistolary story, Philyaw grew up with four half-sisters who shared a largely absent father, and, like the siblings in the story, she and her sisters decided to make contact with their fifth half-sister when their father died. “Unfortunately, we all four of us called her at once, which is not something that I would advise,” she says, admitting that the fictional letter is a kind of “do-over”.

Another “kernel” of her own life in Church Ladies is Philyaw’s identity as a queer woman, a label she has only just started to use. Despite “queer” feeling more accurate than “straight” in terms of her desires and life experiences, she was reluctant to use the word. “I felt like I was claiming something that I had no right to claim, because I had all of these privileges and protections, having been married to men twice.” She recently sought “permission” to call herself queer from LGBT+ friends and family. “They reminded me that I don’t have to answer to anybody.”

That need for approval from the people we love – and the damage that can be caused when we don’t get it – is explored in Snowfall, one of the most heart-wrenching stories in the collection. Arletha, who lives with her partner, Rhonda, in Pittsburgh, desperately misses her mother and the south, where she’s from, but her family relationships were all but destroyed when she came out as gay. With characters that can touch you so immediately, it’s hardly surprising that the screen rights to Church Ladies have been snapped up by HBO – Philyaw is currently working on the script.

It also sounds as though the novel that she has been working on for more than a decade – the story of a preacher’s wife – might finally be coming together. If it’s anything like its predecessor, readers can expect to be touched by the warmth and wisdom of Philyaw’s writing – and left ever-so-slightly hungry for a slice of dessert.

When asked to choose their favourite story in The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, Deesha Philyaw’s acclaimed debut collection, most people, the author tells me, say Peach Cobbler. This simultaneously funny and punch-in-the-guts-devastating tale focuses on Olivia, a young girl in the American south who believes the local pastor to be God, because when he visits she overhears her mother screaming “Oh, God!” from the bedroom.

Central to the story is the “best cobbler in the world” – a fruit pie that Olivia’s mother bakes for her lover each week, but which Olivia is forbidden from tasting. Philyaw set out, she tells me from her home in Pennsylvania, to write about “the Blackest dessert”, and peach cobbler came to mind. “In fact, the Blackest dessert is not peach cobbler, it’s pound cake,” she remarks in retrospect. “But I think my brain knew that there was more to peach cobbler than just the Blackness – there’s the textures, the sweetness, the sensuality of it.”

Whatever she was writing, the 50-year-old from Jacksonville, Florida kept coming back to her childhood and the “secret lives” of the women she knew then. Having been sent to church from a young age by her mother and grandmother (who did not attend church themselves), Philyaw had always been curious about the southern Black women around her and how they navigated the “rules” set by the church. “Early on, we were taught that sex was an absolute no, and that anything that happened to you sexually was your fault,” she remembers. As she grew older and started to experiment sexually herself, she continued to wonder about the other women in church: “Did they think sex was bad? Did they like it? Did they masturbate? And how did they grapple with these questions?”

The characters in Church Ladies, which has picked up a National Book Award nomination and won the PEN/Faulkner award, the LA Times book prize and The Story Prize in the US prior to its UK release this week, respond in different ways. There’s Eula, who insists on “saving herself” for marriage to a man, but happily celebrates her birthday each year by having sex with her female best friend; there’s an unnamed bakery owner, implied to be an older Olivia from Peach Cobbler, who provides married men with a set of instructions before they begin an affair with her; and there’s Lyra, who is forced to address the shame she feels around sex when she falls in love at the age of 42.

Philyaw and I are speaking over video call: me in London, mortified to find I’ve got the writer up at 6am; her in Pittsburgh, serene and cheerful, insisting that she is usually awake at this time anyway. She hadn’t always wanted to be a writer, I learn. As a first-generation university student, Philyaw was “aiming to go to college and do something practical and make a lot of money”. If she’d told her family she had literary ambitions, she says, “I might as well have said I want to be Michael Jackson”.

So she went to Yale, got a degree in economics, and initially worked as a management consultant (“I cried every day for months”) before retraining as a teacher, a job she “absolutely loved”. But when Philyaw and her then-husband decided to have children, she gave up teaching to stay at home with her eldest daughter, and started writing “just to do something that was stimulating for myself”. In 2005 she tentatively decided to try to make a living from her hobby.

While she was trying to write a novel, her first published book was a co-parenting guide that she wrote with her ex-husband, a project that came about almost by accident. Friends had dubbed the pair the “poster children for divorce” because of the way they handled their parenting responsibilities after separating, and the book grew from there. Writing Co-Parenting 101 landed Philyaw an agent, bringing her dream of having a novel published one step closer.

It was during a break from the difficult work of novel writing that Church Ladies started to come together. Philyaw had written short fiction in response to competitions and call-outs and hadn’t noticed that her stories tended to share a common theme. It was only when her agent started to refer to them as “church lady stories” that she realised she had been subconsciously zooming in on the questions of her childhood.

The resulting collection is so astute on the particular kind of sexual shame that strict religious teaching can cause that I’m surprised when Philyaw tells me she “didn’t have that kind of baggage” herself. While she attended church until the age of 35, she never felt fully subscribed to Christianity or beholden to its rules. When her mother, father and grandmother all died in the same year, she stopped going altogether – not because she was angry at God, but because she felt nothing there at all. “Why am I getting up on Sunday mornings, the one morning that I can sleep in?” she asked herself. “Because I’m not getting anything out of this.”

Fifteen years later, she is able to reflect on why the church stigmatises sex so much. It comes down to the Black American Christian community’s roots in slavery, she believes. “Slavery was justified, in part, by saying that we weren’t human, and that Black women in particular were promiscuous and hypersexual.” So after emancipation, when churches became cornerstone institutions for the Black community, the response was often: “We’re going to be the opposite of that: we’re going to be pure and we’re going to be blameless, and we’re going to conduct ourselves with propriety.”

This attitude has led to the decades of generational shame that Philyaw has been observing all her life – but the writer doesn’t want to entirely condemn Christianity. Her hope was that Church Ladies would challenge the church’s misogyny and “obsession with sex”, without demonising the institution altogether. Similarly, she has tried not to make villains out of the men in her stories. In fact, although the impact of a wider misogynistic culture is certainly felt, men don’t actually appear much. Philyaw thinks her friend Damon Young, an early reader of the book, describes it best. “He said, the men in this book are like garnish: they’re on the plate, but they’re not the meal. And I thought, that’s it. I definitely wanted to keep the women centred, but I certainly wasn’t trying to thumb my nose at the men.”

The absence of men, particularly of father figures, is perhaps reflective of Philyaw’s own experience. Although none of the stories is directly based on the author’s life, she admits there are “kernels” of herself in there, and that “one of the biggest kernels is in the story Dear Sister”. Like Nichelle, the protagonist of the epistolary story, Philyaw grew up with four half-sisters who shared a largely absent father, and, like the siblings in the story, she and her sisters decided to make contact with their fifth half-sister when their father died. “Unfortunately, we all four of us called her at once, which is not something that I would advise,” she says, admitting that the fictional letter is a kind of “do-over”.

Another “kernel” of her own life in Church Ladies is Philyaw’s identity as a queer woman, a label she has only just started to use. Despite “queer” feeling more accurate than “straight” in terms of her desires and life experiences, she was reluctant to use the word. “I felt like I was claiming something that I had no right to claim, because I had all of these privileges and protections, having been married to men twice.” She recently sought “permission” to call herself queer from LGBT+ friends and family. “They reminded me that I don’t have to answer to anybody.”

That need for approval from the people we love – and the damage that can be caused when we don’t get it – is explored in Snowfall, one of the most heart-wrenching stories in the collection. Arletha, who lives with her partner, Rhonda, in Pittsburgh, desperately misses her mother and the south, where she’s from, but her family relationships were all but destroyed when she came out as gay. With characters that can touch you so immediately, it’s hardly surprising that the screen rights to Church Ladies have been snapped up by HBO – Philyaw is currently working on the script.

It also sounds as though the novel that she has been working on for more than a decade – the story of a preacher’s wife – might finally be coming together. If it’s anything like its predecessor, readers can expect to be touched by the warmth and wisdom of Philyaw’s writing – and left ever-so-slightly hungry for a slice of dessert.