The Facemaker by Lindsey Fitzharris review – transforming the wounded | History books

For many men fighting in the first world war, the fear of being permanently disabled was more terrifying than death. Yet worse even than the prospect of a life-changing disability was the horror of facial disfigurement. While men who lost a limb were treated as heroes, those who suffered facial injuries were often shunned or reviled. Mothers hurried their children indoors to avoid seeing these disfigured men; women broke off engagements with their mutilated fiances.

Harold Gillies, a New Zealand-born surgeon who trained in Britain, helped thousands of men to literally face the world again. His work in the unit he created at the Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, has been overshadowed by the more familiar story of his cousin, Archibald McIndoe, who rebuilt the burnt faces of pilots in his “Guinea Pig Club” in the second world war. Yet it was Gillies, an extraordinarily compassionate man as well as a skilled surgeon, who really transformed the speciality of plastic surgery.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind the scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

In her engrossing book, Lindsey Fitzharris not only tells the story of Gillies’s achievements, she immerses us in the world of the men he helped, following them from the carnage of the trenches to the wards where they made long and painful recoveries.

Gillies was 32 when war broke out. He joined the Red Cross and was sent to France in 1915, where he first encountered men with appalling facial injuries caused by shells, shrapnel and sniper bullets. Plastic surgery was in its infancy. A few enterprising doctors had attempted reconstructive operations but mainly on noses and ears and with variable results. Some operations enabled patients to eat and speak but left gaping holes. Gillies realised that a specialist facial surgery centre was needed where patients would receive expert treatment and surgeons could perfect their skills.

He was first allotted a ward at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot, where he recruited a multidisciplinary team including dentists, nurses and an anaesthetist along with an artist to document their work. Before long, he was given his own dedicated centre in Sidcup, in a Georgian mansion surrounded by wooden huts, which opened as the Queen’s Hospital in 1917.

Men arrived with jaws, noses and cheeks destroyed, tongues torn out and eyeballs dislodged. Pilots in aircraft fires, sailors in explosions at sea and soldiers in tanks that caught fire were brought with their faces terribly burnt. Some had already had operations that left their features contorted, so Gillies had to reopen the wounds before beginning reconstruction.

With no textbooks to follow, Gillies had to invent his own solutions, often sketching ideas on an envelope then performing multiple operations involving skin, cartilage and bone grafts. “He would set to work on some man who had had half his face literally blown to pieces with the skin that was left hanging in shreds,” said a nurse who worked alongside him. Gillies took flaps of skin from patients’ chests and elsewhere, leaving them attached by narrow strips to maintain blood supply, then swung them round to cover facial wounds. In one landmark operation, he sewed the strips into tubes – or “pedicules” – which reduced the risk of infection. Using these techniques, Gillies recreated noses, jaws, lips and eyelids. One man underwent 40 operations to rebuild his nose.

To maintain morale, the hospital ran sports days and staged amateur dramatics. Patients were encouraged to walk the local streets where some benches were painted blue so that passersby would be warned in advance that a disfigured man might be sitting there. After the war, Gillies set up a private practice where he performed more pioneering operations including, in 1949, the first female-to-male gender reassignment.

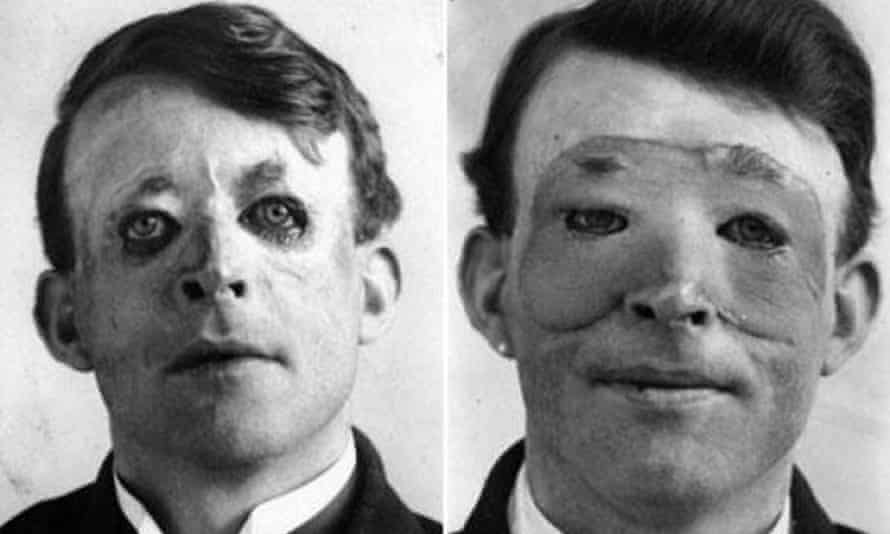

This is not a book for the fainthearted. Meticulously clear and detailed accounts of gruesome injuries and gruelling operations are supplemented by stunning portraits by the war artist Henry Tonks, who depicted patients before and after their reconstructions. Despite its harrowing subject, however, Fitzharris presents an intensely moving and hugely enjoyable story about a remarkable medical pioneer and the men he remade.

For many men fighting in the first world war, the fear of being permanently disabled was more terrifying than death. Yet worse even than the prospect of a life-changing disability was the horror of facial disfigurement. While men who lost a limb were treated as heroes, those who suffered facial injuries were often shunned or reviled. Mothers hurried their children indoors to avoid seeing these disfigured men; women broke off engagements with their mutilated fiances.

Harold Gillies, a New Zealand-born surgeon who trained in Britain, helped thousands of men to literally face the world again. His work in the unit he created at the Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, has been overshadowed by the more familiar story of his cousin, Archibald McIndoe, who rebuilt the burnt faces of pilots in his “Guinea Pig Club” in the second world war. Yet it was Gillies, an extraordinarily compassionate man as well as a skilled surgeon, who really transformed the speciality of plastic surgery.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind the scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

In her engrossing book, Lindsey Fitzharris not only tells the story of Gillies’s achievements, she immerses us in the world of the men he helped, following them from the carnage of the trenches to the wards where they made long and painful recoveries.

Gillies was 32 when war broke out. He joined the Red Cross and was sent to France in 1915, where he first encountered men with appalling facial injuries caused by shells, shrapnel and sniper bullets. Plastic surgery was in its infancy. A few enterprising doctors had attempted reconstructive operations but mainly on noses and ears and with variable results. Some operations enabled patients to eat and speak but left gaping holes. Gillies realised that a specialist facial surgery centre was needed where patients would receive expert treatment and surgeons could perfect their skills.

He was first allotted a ward at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot, where he recruited a multidisciplinary team including dentists, nurses and an anaesthetist along with an artist to document their work. Before long, he was given his own dedicated centre in Sidcup, in a Georgian mansion surrounded by wooden huts, which opened as the Queen’s Hospital in 1917.

Men arrived with jaws, noses and cheeks destroyed, tongues torn out and eyeballs dislodged. Pilots in aircraft fires, sailors in explosions at sea and soldiers in tanks that caught fire were brought with their faces terribly burnt. Some had already had operations that left their features contorted, so Gillies had to reopen the wounds before beginning reconstruction.

With no textbooks to follow, Gillies had to invent his own solutions, often sketching ideas on an envelope then performing multiple operations involving skin, cartilage and bone grafts. “He would set to work on some man who had had half his face literally blown to pieces with the skin that was left hanging in shreds,” said a nurse who worked alongside him. Gillies took flaps of skin from patients’ chests and elsewhere, leaving them attached by narrow strips to maintain blood supply, then swung them round to cover facial wounds. In one landmark operation, he sewed the strips into tubes – or “pedicules” – which reduced the risk of infection. Using these techniques, Gillies recreated noses, jaws, lips and eyelids. One man underwent 40 operations to rebuild his nose.

To maintain morale, the hospital ran sports days and staged amateur dramatics. Patients were encouraged to walk the local streets where some benches were painted blue so that passersby would be warned in advance that a disfigured man might be sitting there. After the war, Gillies set up a private practice where he performed more pioneering operations including, in 1949, the first female-to-male gender reassignment.

This is not a book for the fainthearted. Meticulously clear and detailed accounts of gruesome injuries and gruelling operations are supplemented by stunning portraits by the war artist Henry Tonks, who depicted patients before and after their reconstructions. Despite its harrowing subject, however, Fitzharris presents an intensely moving and hugely enjoyable story about a remarkable medical pioneer and the men he remade.