Achieving linguistic justice for African American English

African American English (AAE) is a variety of English spoken primarily, though not exclusively, by Black Americans of historical African descent.

Because AAE varies from white American English (WAE) in a systematic way, it is possible that speech and hearing specialists unfamiliar with the language variety could misidentify differences in speech production as speech disorder. Professional understanding of the difference between typical variation and errors in the language system is the first step for accurately identifying disorder and establishing linguistic justice for AAE speakers.

In her presentation, “Kids talk too: Linguistic justice and child African American English,” Yolanda Holt of East Carolina University described aspects of the systematic variation between AAE and WAE speech production in children. The talk took place Wednesday, May 10 as part of the 184th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Common characteristics of AAE speech include variation at all linguistic levels, from sound production at the word level to the choice of commentary in professional interpersonal interactions. A frequent feature of AAE is final consonant reduction/deletion and final consonant cluster reduction. Holt provided the following example to illustrate word level to interpersonal level linguistic variation.

“In the professional setting, if one AAE-speaking professional woman wanted to compliment the attire of the other, the exchange might sound something like this: [Speaker 1] ‘I see you rockin’ the tone on tone.’ [Speaker 2] ‘Frien’, I’m jus’ tryin’ to be like you wit’ the fully executive flex.'”

This example, in addition to using common aspects of AAE word shape, shows how the choice to use AAE in a professional setting is a way for the two women to share a message beyond the words.

“This exchange illustrates a complex and nuanced cultural understanding between the two speakers. In a few words, they communicate professional respect and a subtle appreciation for the intricate balance that African American women navigate in bringing their whole selves to the corporate setting,” said Holt.

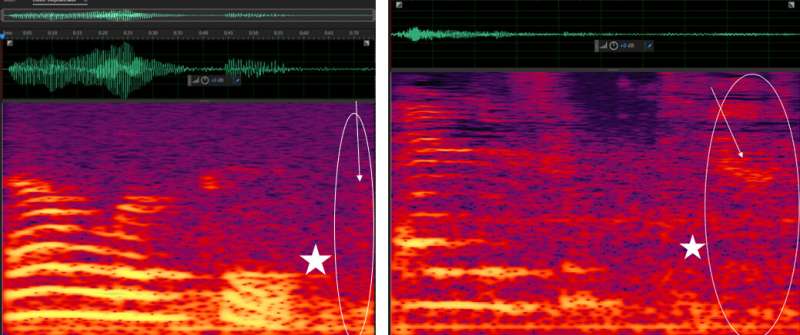

Holt and her team examined final consonant cluster reduction (e.g., expressing “shift” as “shif'”) in 4- and 5-year-old children. Using instrumental acoustic phonetic analysis, they discovered that the variation in final consonant production in AAE is likely not a wholesale elimination of word endings but is perhaps a difference in aspects of articulation.

“This is an important finding because it could be assumed that if a child does not fully articulate the final sound, they are not aware of its existence,” said Holt. “By illustrating that the AAE-speaking child produces a variation of the final sound, not a wholesale removal, we help to eliminate the mistaken idea that AAE speakers don’t know the ending sounds exist.”

Holt believes the fields of speech and language science, education, and computer science should expect and accept such variation in human communication. Linguistic justice occurs when we accept variation in human language without penalizing the user or defining their speech as “wrong.”

“Language is alive. It grows and changes over each generation,” said Holt. “Accepting the speech and language used by each generation and each group of speakers is an acceptance of the individual, their life, and their experience. Acceptance, not tolerance, is the next step in the march towards linguistic justice. For that to occur, we must learn from our speakers and educate our professionals that different can be typical. It is not always disordered.”

Citation:

Achieving linguistic justice for African American English (2023, May 10)

retrieved 10 May 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-05-linguistic-justice-african-american-english.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

African American English (AAE) is a variety of English spoken primarily, though not exclusively, by Black Americans of historical African descent.

Because AAE varies from white American English (WAE) in a systematic way, it is possible that speech and hearing specialists unfamiliar with the language variety could misidentify differences in speech production as speech disorder. Professional understanding of the difference between typical variation and errors in the language system is the first step for accurately identifying disorder and establishing linguistic justice for AAE speakers.

In her presentation, “Kids talk too: Linguistic justice and child African American English,” Yolanda Holt of East Carolina University described aspects of the systematic variation between AAE and WAE speech production in children. The talk took place Wednesday, May 10 as part of the 184th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Common characteristics of AAE speech include variation at all linguistic levels, from sound production at the word level to the choice of commentary in professional interpersonal interactions. A frequent feature of AAE is final consonant reduction/deletion and final consonant cluster reduction. Holt provided the following example to illustrate word level to interpersonal level linguistic variation.

“In the professional setting, if one AAE-speaking professional woman wanted to compliment the attire of the other, the exchange might sound something like this: [Speaker 1] ‘I see you rockin’ the tone on tone.’ [Speaker 2] ‘Frien’, I’m jus’ tryin’ to be like you wit’ the fully executive flex.'”

This example, in addition to using common aspects of AAE word shape, shows how the choice to use AAE in a professional setting is a way for the two women to share a message beyond the words.

“This exchange illustrates a complex and nuanced cultural understanding between the two speakers. In a few words, they communicate professional respect and a subtle appreciation for the intricate balance that African American women navigate in bringing their whole selves to the corporate setting,” said Holt.

Holt and her team examined final consonant cluster reduction (e.g., expressing “shift” as “shif'”) in 4- and 5-year-old children. Using instrumental acoustic phonetic analysis, they discovered that the variation in final consonant production in AAE is likely not a wholesale elimination of word endings but is perhaps a difference in aspects of articulation.

“This is an important finding because it could be assumed that if a child does not fully articulate the final sound, they are not aware of its existence,” said Holt. “By illustrating that the AAE-speaking child produces a variation of the final sound, not a wholesale removal, we help to eliminate the mistaken idea that AAE speakers don’t know the ending sounds exist.”

Holt believes the fields of speech and language science, education, and computer science should expect and accept such variation in human communication. Linguistic justice occurs when we accept variation in human language without penalizing the user or defining their speech as “wrong.”

“Language is alive. It grows and changes over each generation,” said Holt. “Accepting the speech and language used by each generation and each group of speakers is an acceptance of the individual, their life, and their experience. Acceptance, not tolerance, is the next step in the march towards linguistic justice. For that to occur, we must learn from our speakers and educate our professionals that different can be typical. It is not always disordered.”

Citation:

Achieving linguistic justice for African American English (2023, May 10)

retrieved 10 May 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-05-linguistic-justice-african-american-english.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.