Best Practices for Writing Reproducible and Maintainable Jupyter Notebooks | by Daniel Etzold | Jul, 2022

Simple steps to make your Jupyter Notebooks great

Writing Jupyter Notebooks that are reproducible, maintainable, and easy to understand is not as easy as you might think. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. It’s actually really hard. In this article, I’m going to explain why it is so hard and give you some recommendations for best practices that helped me to achieve better reproducibility and maintainability.

First, let me give you a short introduction what Jupiter Notebooks are. Basically, a Jupyter Notebook is an interactive document. You can write plain text with Markdown syntax and also use mathematical formulas via LaTeX syntax. Additionally, you can add code to a notebook that the reader can execute to produce some output such as a visualization.

For instance, you could visualize a function that is based on various parameters. The reader could use sliders to change the values of these parameters and the visualization is updated every time a value is changed (see the example below). You could also add code that performs live queries to some database to get the latest sales numbers and to plot them in an pie chart for instance.

The code is typically written in Python. However, more than 100 programming languages are supported such as Java, R, Julia, Scala and so on. Notebooks can be written and executed in the browser. However, even though writing notebooks in the browser is possible (rudimentary code completion exists), it’s limited. Fortunately, you can also use IDEs such as Visual Studio Code or PyCharm (in the Professional version) which provide more powerful features.

You can also use cloud services to write and execute notebooks. Google, for instance, provides with Google Colab a solution that allows you to run notebooks in the cloud and share them with everyone. Even GPUs can be accessed in Google Colab for free for intensive computational tasks.

Below you can see an example of a Jupyter Notebook which explains how to approximate π with a Monte Carlo Method. You can see three cells. The first cell is a Markdown cell which gives an introduction to the notebook. It contains, text, an animation and some simple math equations which are rendered via MathJax.

The second cell is a code cell that contains Python code. If this cell is executed the code produces a simple plot of a circle within a square.

The third cell is a Markdown cell again which jumps between editing mode and the rendered result when the cell is executed. In editing mode you can see the plain Markdown text.

Jupyter Notebooks have become very popular. In October 2020 roughly 10 million public notebooks were available on GitHub. Notebooks are especially popular in the academic community for educational purposes. Also data scientists are heavily using notebooks for data analysis and exploratory task.

In particular the combination of text and code makes them very interesting. It allows the author to explain concepts in Markdown with expressive formulas and at the same time it’s possible to show an implementation as code in the same document. This unique characteristic of Jupyter Notebooks allows better reproducibility of research results and distribution of educational content.

Despite their popularity, Jupyter Notebooks have been subject to criticism (e.g. I don’t like notebooks) as the way you can write code might result in bad habits. Here are some examples:

Naming of Notebooks

One anti-pattern that can be observed sometimes is that notebooks don’t have expressive names. Instead notebooks sometimes start with “Untitled” or end with “-Copy” in their names. This is due to the default behavior of Jupyter running in the browser. Every time you create a new notebook an untitled notebook is created and every time you create a copy of an existing notebook, the new notebook gets the suffix “-Copy”.

You might assume that a lot of notebook names suffer from this anti-pattern if this is the default behavior of Jupyter. But surprisingly, as discovered by a study [1], less than 2% of the notebooks analyzed by the study (a subset of notebooks downloaded from GitHub) actually have “Untitled” and less than 0.7% have “-Copy” in their names. So it doesn’t seem to be a big issue.

However, the same study also found that almost 30% of the examined notebooks have characters in their names that are not recommended by the POSIX fully portable filenames guide which allows only the characters [A-Za-z0–9.-_]. Notebooks with non-portable filenames might cause problems on some systems and therefore should be avoided.

Ambiguous execution order

Cells in a Jupyter notebook can be executed in arbitrary orders. You don’t have to start at the first cell and end with the last cell. You could also start with the second cell, jump back to the first cell and then execute the third cell. You could also execute cells multiple times in a row.

This is also a common behavior when writing a notebook because typically you write some code in a cell, you execute the cell and then you modify and execute the cell again and again until you are satisfied with the results of that cell. Sometimes you also need to go back to a previously executed cell to reinitialize a variable or because you need to modify a previously defined function.

Due to that it’s sometimes difficult to follow the execution order which might negatively affect the notebook’s reproducibility.

In the previously cited study [1] it was found that ambiguous execution order is an issue for many notebooks. 14% of the analyzed notebooks have this issue.

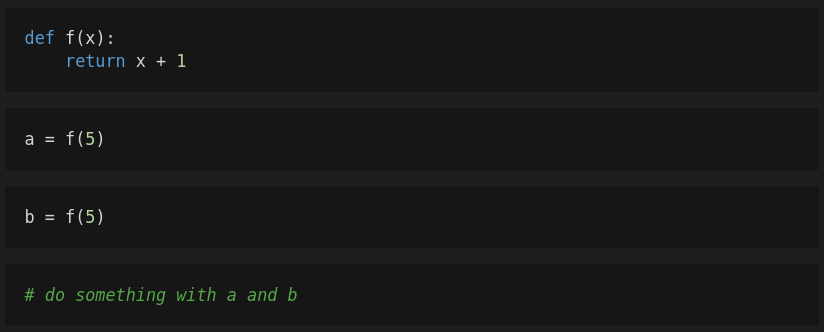

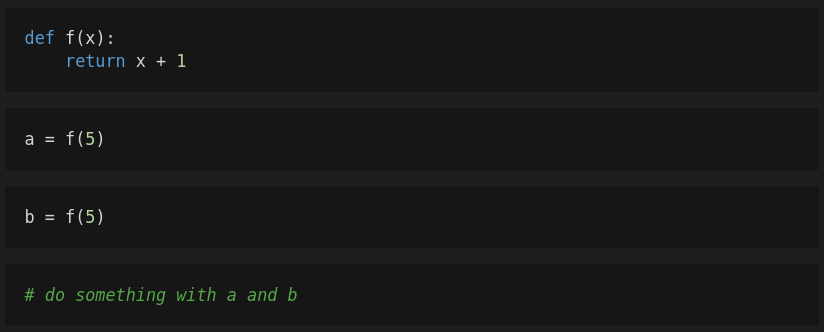

Let’s have a look at a related example that demonstrates an additional problem. In the following you can see 4 cells.

First, you execute the first cell so that the function f is defined. Then you execute the second cell after which the variable a will have the value 6. Next, you’re editing the third cell but decide to slightly change the code of the function f. Instead of incrementing the variable x by one, the function should increment x by two. After you have changed the function, you execute the first cell again so that your changes take effect and then you execute the third cell. The variable b will get the value 7. The following cells are working with these two variables.

If you share this notebook with other people, these people will not be able to reproduce your results because they only see the version of f that increments the variable x by two. If these people execute the notebook step by step the variables a and b will have the value 7 instead of 6 and 7 respectively.

Missing modularization

In [1] it was found that

- only 10% of the analyzed notebooks had local imports (i.e. imports of modules stored in the repository directory)

- 54% of the notebooks define functions

- less than 9% of the notebooks define classes

These results show that modularization isn’t used often for Jupyter Notebooks. This is interesting as modularization is a well established pattern in software engineering with many benefits. It helps to

- reduce code (e.g. less copy&paste)

- split complex code into smaller pieces that are easier to understand

- produce code that can be tested more easily

- reduce the number of global variables in a notebook which can result in lower memory usage (local variables get freed more often as they exist only in their local scope)

However, not using modularization can have many reasons. For instance, notebooks without functions may be simple enough so that this abstraction is not required. A notebook might also not use modules because the author wants to simplify the distribution of a notebook. This is easier if just one single file needs to be distributed instead of multiple files which would be the case if code is moved into modules.

Missing tests

In software engineering testing is a common practice. Various testing strategies exist such as integration testing, regression testing or unit testing. You can find a nice overview of different approaches on Wikipedia. Unit tests, for instance, are automatic tests which test small pieces of a software, typically a single function.

Various frameworks exist for writing unit tests. For Python the module unittest is well established and easy to use. According to [1] only few notebooks (less than 2%) import well known testing modules which might be an indicator that testing is not widely used.

Even though having no tests is an anti-pattern in software engineering in general, it might be reasonable for the majority of notebooks. Many notebooks are used for data analyzing and exploration to test hypothesis or for educational purposes to demonstrate something. Writing tests for these applications often doesn’t make much sense due to missing ground truths in case of analyzing and exploration tasks or because the demonstration produces the expected results.

Missing dependencies

Jupyter Notebooks typically rely on various libraries and packages. In Python these dependencies are imported via the keyword import. A version is not specified for an import and therefore, it’s not possible to identify the required version of a package by just looking at its import. However, if the versions of the dependencies are not documented elsewhere and if there is no easy way to install all the required dependencies, people might have problems executing a notebook because they probably won’t be able to setup the required environment in which the notebook is running.

Furthermore, dependencies don’t need to be imported at the beginning of a notebook. Instead, dependencies can be imported everywhere. Therefore, it might be difficult to identify all required dependencies by just looking at the beginning of a notebook. Instead, you would have to scan the complete code.

And finally, also the name of an import might differ from the name of the package that need to be installed. For instance, to parse YAML files, PyYAML is widely used. This package can be installed via pip install pyyaml. However, to use this package you have to import yaml.

According to [1] many notebooks do not declare module dependencies.

Data inaccessibility

For many notebooks to work data is needed. For instance, notebooks about machine learning usually need a dataset that is used for training. A validation set is used to determine the performance of the model on unknown data. If this data is not distributed with the notebook and does not exist, the results of a notebook cannot be reproduced.

According to [1] inaccessibility of data is a common cause of errors when executing notebooks and two main reasons have been identified. Either the data simply does not exist, or in case the data is distributed with the notebook, absolute paths are used to access the data.

Limited Reproducibility

An essential idea of Jupyter Notebooks is to make results reproducible. This idea is one reason why notebooks gain so much popularity in the scientific community. Here, reproducibility is important because the easier it is to reproduce results the more likely it is that the results produce new insights as others can reuse and build on your work.

However, according to [1] many of the analyzed notebooks on GitHub cannot be reproduced. The results show that only between 22% and 26% of the notebooks could be executed successfully and that even only 4.9% to 15% notebooks produced the same results.

There are basically three reasons for non-reproducible notebooks which we’ve already discussed:

- missing dependencies

- out-of-order execution (and resulting hidden states)

- data inaccessibility

To ensure that notebooks are easy to understand, maintainable and reusable, and furthermore to increase the likelihood that a notebook’s results can be reproduced, the following recommendations might be very helpful:

- Use expressive names for your notebooks that describe what your notebook is doing and use only characters that are included in the POSIX fully portable filenames guide.

- Avoid ambiguous execution orders. To ensure that your notebook is reproducible and creates the expected results, restart the kernel and execute all cells of the notebook before you share your notebook.

- Use modularization (i.e. modules, functions, classes) if reasonable.

- Use testing frameworks to test your code if reasonable.

- Ensure that all data used in the notebook is distributed together with the notebook (or at least can be downloaded) and that you’re using relative paths to access the data.

- Create a requirements.txt to pin the versions of all used dependencies and import all dependencies at the beginning of a notebook.

- Distribute a notebook with its outputs. This makes it easier to reproduce the results as everyone who executes the notebook can verify that the results are the same.

- Do not redefine variables.

Jupyter Notebooks are easy to write, but various studies have revealed that it seems to be hard to write reproducible notebooks. However, if you follow some common best practices, it indeed becomes more likely that your notebooks can be reproduced, and that others can build on your great work. These best practices also helped me to write good notebooks. From my point of view, avoiding ambiguous execution orders, providing a list of used dependencies with their versions, and making the data that is used in the notebook easily accessible are the most important ones.

[1] Pimentel, João Felipe, et al. “Understanding and improving the quality and reproducibility of Jupyter notebooks.” Empirical Software Engineering 26.4 (2021): 1–55.

Simple steps to make your Jupyter Notebooks great

Writing Jupyter Notebooks that are reproducible, maintainable, and easy to understand is not as easy as you might think. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. It’s actually really hard. In this article, I’m going to explain why it is so hard and give you some recommendations for best practices that helped me to achieve better reproducibility and maintainability.

First, let me give you a short introduction what Jupiter Notebooks are. Basically, a Jupyter Notebook is an interactive document. You can write plain text with Markdown syntax and also use mathematical formulas via LaTeX syntax. Additionally, you can add code to a notebook that the reader can execute to produce some output such as a visualization.

For instance, you could visualize a function that is based on various parameters. The reader could use sliders to change the values of these parameters and the visualization is updated every time a value is changed (see the example below). You could also add code that performs live queries to some database to get the latest sales numbers and to plot them in an pie chart for instance.

The code is typically written in Python. However, more than 100 programming languages are supported such as Java, R, Julia, Scala and so on. Notebooks can be written and executed in the browser. However, even though writing notebooks in the browser is possible (rudimentary code completion exists), it’s limited. Fortunately, you can also use IDEs such as Visual Studio Code or PyCharm (in the Professional version) which provide more powerful features.

You can also use cloud services to write and execute notebooks. Google, for instance, provides with Google Colab a solution that allows you to run notebooks in the cloud and share them with everyone. Even GPUs can be accessed in Google Colab for free for intensive computational tasks.

Below you can see an example of a Jupyter Notebook which explains how to approximate π with a Monte Carlo Method. You can see three cells. The first cell is a Markdown cell which gives an introduction to the notebook. It contains, text, an animation and some simple math equations which are rendered via MathJax.

The second cell is a code cell that contains Python code. If this cell is executed the code produces a simple plot of a circle within a square.

The third cell is a Markdown cell again which jumps between editing mode and the rendered result when the cell is executed. In editing mode you can see the plain Markdown text.

Jupyter Notebooks have become very popular. In October 2020 roughly 10 million public notebooks were available on GitHub. Notebooks are especially popular in the academic community for educational purposes. Also data scientists are heavily using notebooks for data analysis and exploratory task.

In particular the combination of text and code makes them very interesting. It allows the author to explain concepts in Markdown with expressive formulas and at the same time it’s possible to show an implementation as code in the same document. This unique characteristic of Jupyter Notebooks allows better reproducibility of research results and distribution of educational content.

Despite their popularity, Jupyter Notebooks have been subject to criticism (e.g. I don’t like notebooks) as the way you can write code might result in bad habits. Here are some examples:

Naming of Notebooks

One anti-pattern that can be observed sometimes is that notebooks don’t have expressive names. Instead notebooks sometimes start with “Untitled” or end with “-Copy” in their names. This is due to the default behavior of Jupyter running in the browser. Every time you create a new notebook an untitled notebook is created and every time you create a copy of an existing notebook, the new notebook gets the suffix “-Copy”.

You might assume that a lot of notebook names suffer from this anti-pattern if this is the default behavior of Jupyter. But surprisingly, as discovered by a study [1], less than 2% of the notebooks analyzed by the study (a subset of notebooks downloaded from GitHub) actually have “Untitled” and less than 0.7% have “-Copy” in their names. So it doesn’t seem to be a big issue.

However, the same study also found that almost 30% of the examined notebooks have characters in their names that are not recommended by the POSIX fully portable filenames guide which allows only the characters [A-Za-z0–9.-_]. Notebooks with non-portable filenames might cause problems on some systems and therefore should be avoided.

Ambiguous execution order

Cells in a Jupyter notebook can be executed in arbitrary orders. You don’t have to start at the first cell and end with the last cell. You could also start with the second cell, jump back to the first cell and then execute the third cell. You could also execute cells multiple times in a row.

This is also a common behavior when writing a notebook because typically you write some code in a cell, you execute the cell and then you modify and execute the cell again and again until you are satisfied with the results of that cell. Sometimes you also need to go back to a previously executed cell to reinitialize a variable or because you need to modify a previously defined function.

Due to that it’s sometimes difficult to follow the execution order which might negatively affect the notebook’s reproducibility.

In the previously cited study [1] it was found that ambiguous execution order is an issue for many notebooks. 14% of the analyzed notebooks have this issue.

Let’s have a look at a related example that demonstrates an additional problem. In the following you can see 4 cells.

First, you execute the first cell so that the function f is defined. Then you execute the second cell after which the variable a will have the value 6. Next, you’re editing the third cell but decide to slightly change the code of the function f. Instead of incrementing the variable x by one, the function should increment x by two. After you have changed the function, you execute the first cell again so that your changes take effect and then you execute the third cell. The variable b will get the value 7. The following cells are working with these two variables.

If you share this notebook with other people, these people will not be able to reproduce your results because they only see the version of f that increments the variable x by two. If these people execute the notebook step by step the variables a and b will have the value 7 instead of 6 and 7 respectively.

Missing modularization

In [1] it was found that

- only 10% of the analyzed notebooks had local imports (i.e. imports of modules stored in the repository directory)

- 54% of the notebooks define functions

- less than 9% of the notebooks define classes

These results show that modularization isn’t used often for Jupyter Notebooks. This is interesting as modularization is a well established pattern in software engineering with many benefits. It helps to

- reduce code (e.g. less copy&paste)

- split complex code into smaller pieces that are easier to understand

- produce code that can be tested more easily

- reduce the number of global variables in a notebook which can result in lower memory usage (local variables get freed more often as they exist only in their local scope)

However, not using modularization can have many reasons. For instance, notebooks without functions may be simple enough so that this abstraction is not required. A notebook might also not use modules because the author wants to simplify the distribution of a notebook. This is easier if just one single file needs to be distributed instead of multiple files which would be the case if code is moved into modules.

Missing tests

In software engineering testing is a common practice. Various testing strategies exist such as integration testing, regression testing or unit testing. You can find a nice overview of different approaches on Wikipedia. Unit tests, for instance, are automatic tests which test small pieces of a software, typically a single function.

Various frameworks exist for writing unit tests. For Python the module unittest is well established and easy to use. According to [1] only few notebooks (less than 2%) import well known testing modules which might be an indicator that testing is not widely used.

Even though having no tests is an anti-pattern in software engineering in general, it might be reasonable for the majority of notebooks. Many notebooks are used for data analyzing and exploration to test hypothesis or for educational purposes to demonstrate something. Writing tests for these applications often doesn’t make much sense due to missing ground truths in case of analyzing and exploration tasks or because the demonstration produces the expected results.

Missing dependencies

Jupyter Notebooks typically rely on various libraries and packages. In Python these dependencies are imported via the keyword import. A version is not specified for an import and therefore, it’s not possible to identify the required version of a package by just looking at its import. However, if the versions of the dependencies are not documented elsewhere and if there is no easy way to install all the required dependencies, people might have problems executing a notebook because they probably won’t be able to setup the required environment in which the notebook is running.

Furthermore, dependencies don’t need to be imported at the beginning of a notebook. Instead, dependencies can be imported everywhere. Therefore, it might be difficult to identify all required dependencies by just looking at the beginning of a notebook. Instead, you would have to scan the complete code.

And finally, also the name of an import might differ from the name of the package that need to be installed. For instance, to parse YAML files, PyYAML is widely used. This package can be installed via pip install pyyaml. However, to use this package you have to import yaml.

According to [1] many notebooks do not declare module dependencies.

Data inaccessibility

For many notebooks to work data is needed. For instance, notebooks about machine learning usually need a dataset that is used for training. A validation set is used to determine the performance of the model on unknown data. If this data is not distributed with the notebook and does not exist, the results of a notebook cannot be reproduced.

According to [1] inaccessibility of data is a common cause of errors when executing notebooks and two main reasons have been identified. Either the data simply does not exist, or in case the data is distributed with the notebook, absolute paths are used to access the data.

Limited Reproducibility

An essential idea of Jupyter Notebooks is to make results reproducible. This idea is one reason why notebooks gain so much popularity in the scientific community. Here, reproducibility is important because the easier it is to reproduce results the more likely it is that the results produce new insights as others can reuse and build on your work.

However, according to [1] many of the analyzed notebooks on GitHub cannot be reproduced. The results show that only between 22% and 26% of the notebooks could be executed successfully and that even only 4.9% to 15% notebooks produced the same results.

There are basically three reasons for non-reproducible notebooks which we’ve already discussed:

- missing dependencies

- out-of-order execution (and resulting hidden states)

- data inaccessibility

To ensure that notebooks are easy to understand, maintainable and reusable, and furthermore to increase the likelihood that a notebook’s results can be reproduced, the following recommendations might be very helpful:

- Use expressive names for your notebooks that describe what your notebook is doing and use only characters that are included in the POSIX fully portable filenames guide.

- Avoid ambiguous execution orders. To ensure that your notebook is reproducible and creates the expected results, restart the kernel and execute all cells of the notebook before you share your notebook.

- Use modularization (i.e. modules, functions, classes) if reasonable.

- Use testing frameworks to test your code if reasonable.

- Ensure that all data used in the notebook is distributed together with the notebook (or at least can be downloaded) and that you’re using relative paths to access the data.

- Create a requirements.txt to pin the versions of all used dependencies and import all dependencies at the beginning of a notebook.

- Distribute a notebook with its outputs. This makes it easier to reproduce the results as everyone who executes the notebook can verify that the results are the same.

- Do not redefine variables.

Jupyter Notebooks are easy to write, but various studies have revealed that it seems to be hard to write reproducible notebooks. However, if you follow some common best practices, it indeed becomes more likely that your notebooks can be reproduced, and that others can build on your great work. These best practices also helped me to write good notebooks. From my point of view, avoiding ambiguous execution orders, providing a list of used dependencies with their versions, and making the data that is used in the notebook easily accessible are the most important ones.

[1] Pimentel, João Felipe, et al. “Understanding and improving the quality and reproducibility of Jupyter notebooks.” Empirical Software Engineering 26.4 (2021): 1–55.