Record Warm Atlantic Fuels an Unusual Tropical Storm

CLIMATEWIRE | This year’s hurricane season is already breaking records less than a month in. Atlantic temperatures are abnormally warm, and tropical storms are emerging in waters that don’t typically produce them until at least August.

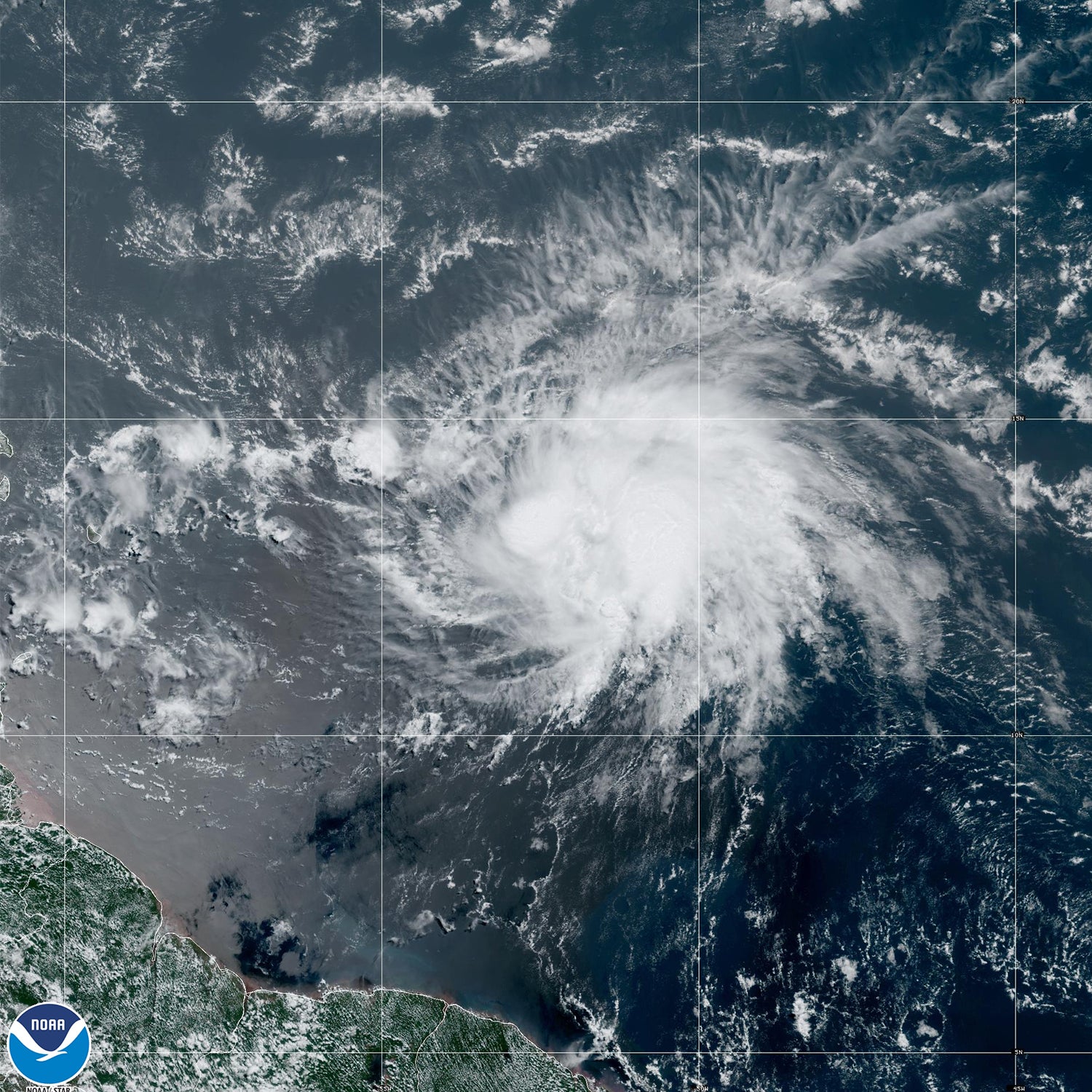

Tropical Storm Bret, the season’s third named storm, formed in the Central Atlantic on Monday after first emerging from a tropical wave off Africa’s western coast. It’s the farthest east a tropical storm has formed in the Atlantic this early in the season, according to hurricane expert Philip Klotzbach at Colorado State University.

According to NOAA, tropical cyclones tend to form in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico earlier in the season and shift eastward as the summer goes on.

Bret is currently churning its way toward the Lesser Antilles, where it’s expected to strike Thursday as a strong tropical storm. The National Hurricane Center predicts that Bret will weaken without developing into a hurricane.

Meanwhile, a second disturbance is also developing in the eastern tropical Atlantic, and the National Hurricane Center predicts that it’s likely to form into a tropical depression in the next few days. According to Klotzbach, no June on record has ever seen two storms form so far east in the tropical Atlantic.

Unusually warm Atlantic waters are to blame. Temperatures in parts of the North Atlantic Ocean basin have broken records this year, and above-average heat has dragged on for weeks.

The continuous influence of human-caused climate change is one factor. Ocean temperatures are steadily rising over time, and global oceans hit their warmest levels on record in 2022 for the fourth year in a row.

But several other factors have converged this year to send Atlantic temperatures skyrocketing.

A natural high-pressure system that swirls in the atmosphere above the Atlantic, known as the Azores High, has been weaker this year than usual, according to hurricane expert Brian McNoldy at the University of Miami. That, in turn, has helped weaken certain wind patterns in the North Atlantic, allowing the water to warm up faster.

In a typical year, these winds also carry large volumes of dust from the Sahara in Africa out over the ocean. This dust blocks sunlight and tends to have a slight regional cooling effect. This year, the weaker winds are transporting less dust, allowing the sun to warm the ocean faster.

Yet despite the unusual start to this year’s hurricane season, it’s still unclear how the rest of the summer will develop.

Scientists have recently declared the arrival of El Niño, a natural cyclical climate phenomenon that causes temperatures in parts of the Pacific Ocean to temporarily rise. El Niño events can have a wide array of effects on global climate and weather patterns, causing droughts in some places, floods in others and often a general increase in global temperatures.

One side effect of El Niño is an increase in wind shear over the Atlantic — that’s a measurement of the way wind changes speed or direction as it moves above the water. More wind shear tends to dampen the development of storms, meaning El Niño years often have reduced hurricane activity.

But warm ocean temperatures, on the other hand, help promote the development of hurricanes. And so far, this year’s record Atlantic heat is favoring unusual development in parts of the ocean that don’t normally see activity until the end of the summer — a sign that, for the moment, the warm waters may be winning out.

Still, hurricane experts have predicted that the tug of war between El Niño and the warm Atlantic will result in average hurricane activity for the rest of the season. NOAA’s hurricane outlook forecasts a 30 percent chance of above-average activity, a 30 percent chance of below-average activity and 40 percent chance of an average season.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2023. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.

CLIMATEWIRE | This year’s hurricane season is already breaking records less than a month in. Atlantic temperatures are abnormally warm, and tropical storms are emerging in waters that don’t typically produce them until at least August.

Tropical Storm Bret, the season’s third named storm, formed in the Central Atlantic on Monday after first emerging from a tropical wave off Africa’s western coast. It’s the farthest east a tropical storm has formed in the Atlantic this early in the season, according to hurricane expert Philip Klotzbach at Colorado State University.

According to NOAA, tropical cyclones tend to form in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico earlier in the season and shift eastward as the summer goes on.

Bret is currently churning its way toward the Lesser Antilles, where it’s expected to strike Thursday as a strong tropical storm. The National Hurricane Center predicts that Bret will weaken without developing into a hurricane.

Meanwhile, a second disturbance is also developing in the eastern tropical Atlantic, and the National Hurricane Center predicts that it’s likely to form into a tropical depression in the next few days. According to Klotzbach, no June on record has ever seen two storms form so far east in the tropical Atlantic.

Unusually warm Atlantic waters are to blame. Temperatures in parts of the North Atlantic Ocean basin have broken records this year, and above-average heat has dragged on for weeks.

The continuous influence of human-caused climate change is one factor. Ocean temperatures are steadily rising over time, and global oceans hit their warmest levels on record in 2022 for the fourth year in a row.

But several other factors have converged this year to send Atlantic temperatures skyrocketing.

A natural high-pressure system that swirls in the atmosphere above the Atlantic, known as the Azores High, has been weaker this year than usual, according to hurricane expert Brian McNoldy at the University of Miami. That, in turn, has helped weaken certain wind patterns in the North Atlantic, allowing the water to warm up faster.

In a typical year, these winds also carry large volumes of dust from the Sahara in Africa out over the ocean. This dust blocks sunlight and tends to have a slight regional cooling effect. This year, the weaker winds are transporting less dust, allowing the sun to warm the ocean faster.

Yet despite the unusual start to this year’s hurricane season, it’s still unclear how the rest of the summer will develop.

Scientists have recently declared the arrival of El Niño, a natural cyclical climate phenomenon that causes temperatures in parts of the Pacific Ocean to temporarily rise. El Niño events can have a wide array of effects on global climate and weather patterns, causing droughts in some places, floods in others and often a general increase in global temperatures.

One side effect of El Niño is an increase in wind shear over the Atlantic — that’s a measurement of the way wind changes speed or direction as it moves above the water. More wind shear tends to dampen the development of storms, meaning El Niño years often have reduced hurricane activity.

But warm ocean temperatures, on the other hand, help promote the development of hurricanes. And so far, this year’s record Atlantic heat is favoring unusual development in parts of the ocean that don’t normally see activity until the end of the summer — a sign that, for the moment, the warm waters may be winning out.

Still, hurricane experts have predicted that the tug of war between El Niño and the warm Atlantic will result in average hurricane activity for the rest of the season. NOAA’s hurricane outlook forecasts a 30 percent chance of above-average activity, a 30 percent chance of below-average activity and 40 percent chance of an average season.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2023. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.