“Shocking” Findings – Scientists Discover How Stress Triggers Cancer’s Spread

New research reveals that stress promotes cancer metastasis by causing neutrophils to form structures that facilitate the disease’s spread. This finding highlights the importance of incorporating stress reduction into cancer treatment and suggests new avenues for preventing cancer metastasis through targeted therapies.

Stress is an unavoidable aspect of life. However, excessive stress can have detrimental effects on our health. Prolonged stress elevates the risk of developing heart disease and experiencing strokes. It may also help cancer spread. How this works has remained a mystery—a challenge for cancer care.

Xue-Yan He, a former postdoc in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Adjunct Professor Mikala Egeblad’s lab, says, “Stress is something we cannot really avoid in cancer patients. You can imagine if you are diagnosed, you cannot stop thinking about the disease or insurance or family. So it is very important to understand how stress works on us.”

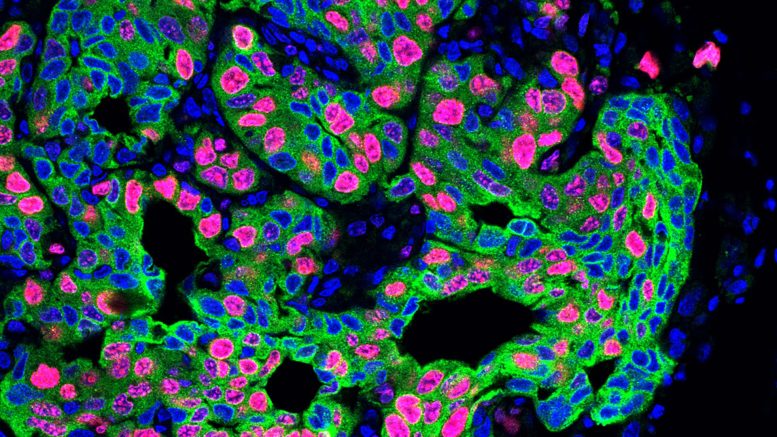

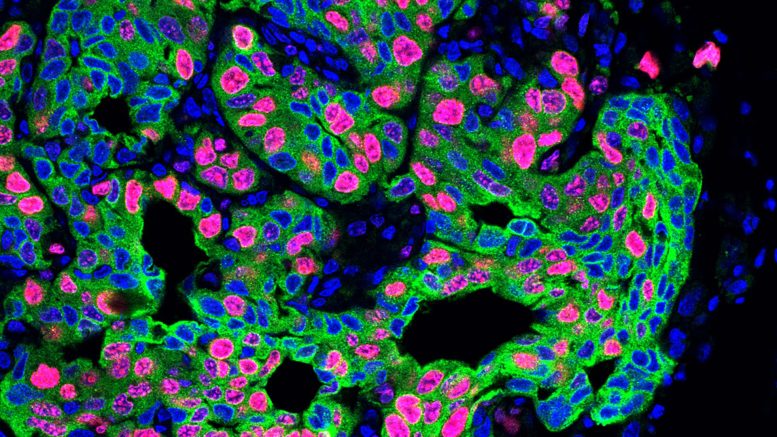

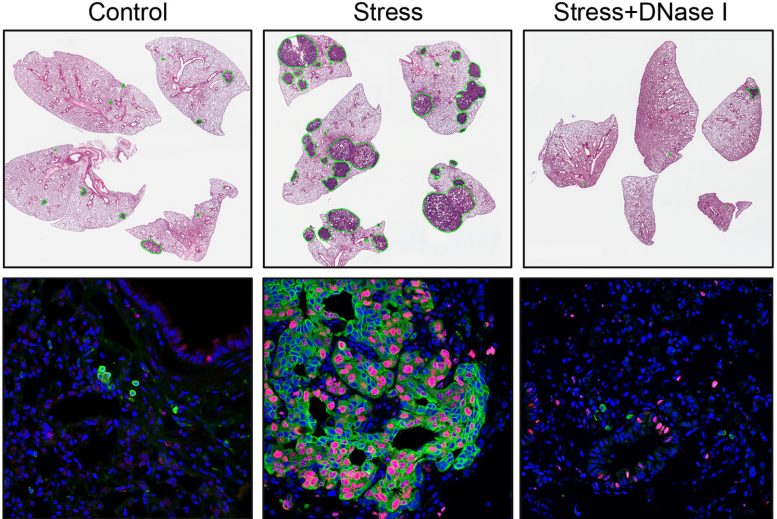

For a recent CSHL Cancer Center study, Adjunct Professor Mikala Egeblad (now a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor with Johns Hopkins University) and postdoc Xue-Yan He (now Assistant Professor of Cell Biology & Physiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis) teamed with CSHL Professor Linda Van Aelst. Above: lung cancer metastasis in a mouse that underwent experiments designed to simulate the stress that cancer patients experience. Credit: Egeblad lab/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Now, He and Egeblad may have reached a breakthrough in understanding exactly that. Working with CSHL Professor Linda Van Aelst, they discovered that stress causes certain white blood cells called neutrophils to form sticky web-like structures that make body tissues more susceptible to metastasis. The finding could point to new treatment strategies that stop cancer’s spread before it starts.

Stress-Induced Metastasis in Mice

The team arrived at their discovery by mimicking chronic stress in mice with cancer. They first removed tumors that had been growing in mice’s breasts and spreading cancer cells to their lungs. Next, they exposed the mice to stress. What He observed was shocking.

“She saw this scary increase in metastatic lesions in these animals. It was up to a fourfold increase in metastasis,” Egeblad recalls.

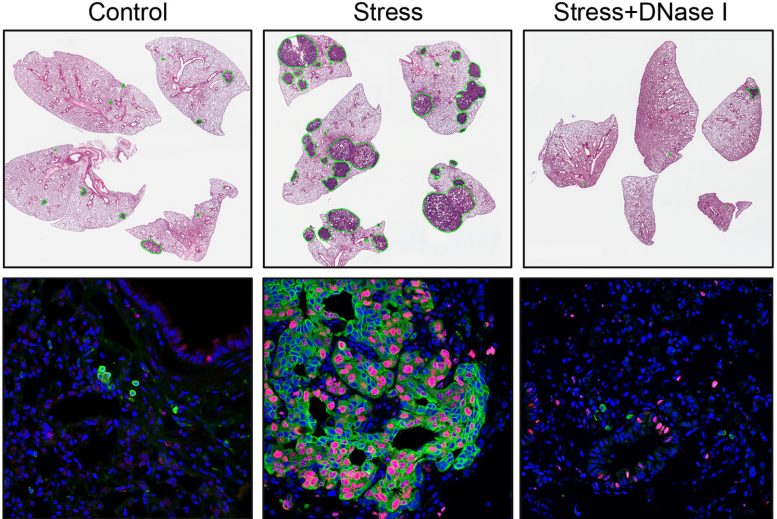

Cancer spread faster and more furiously in stressed mice (middle column) than in a control group (left column). By comparison, cancer cells in stressed mice treated with an enzyme called DNase I (right column) were largely non-proliferating, and the treatment caused a significant reduction in stress-induced metastasis. Credit: Egeblad lab/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

The team found that stress hormones called glucocorticoids acted on the neutrophils. These “stressed” neutrophils formed spider-web-like structures called NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps). NETs form when neutrophils expel DNA. Normally, they can defend us against invading microorganisms. However, in cancer, NETs create a metastasis-friendly environment.

Potential for New Treatment Strategies

To confirm that stress triggers NET formation, leading to increased metastasis, He performed three tests. First, she removed neutrophils from the mice using antibodies. Next, she injected a NET-destroying drug into the animals. Lastly, she used mice whose neutrophils couldn’t respond to glucocorticoids. Each test achieved similar results. “The stressed mice no longer developed more metastasis,” He says.

Notably, the team found that chronic stress caused NET formation to modify lung tissue even in mice without cancer. “It’s almost preparing your tissue for getting cancer,” Egeblad explains.

To Van Aelst, the implication, though startling, is clear. “Reducing stress should be a component of cancer treatment and prevention,” she says.

The team also speculates that future drugs preventing NET formation could benefit patients whose cancer hasn’t yet metastasized. Such new treatments could slow or stop cancer’s spread, offering much-needed relief.

Reference: “Chronic stress increases metastasis via neutrophil-mediated changes to the microenvironment” by Xue-Yan He, Yuan Gao, David Ng, Evdokia Michalopoulou, Shanu George, Jose M. Adrover, Lijuan Sun, Jean Albrengues, Juliane Daßler-Plenker, Xiao Han, Ledong Wan, Xiaoli Sky Wu, Longling S. Shui, Yu-Han Huang, Bodu Liu, Chang Su, David L. Spector, Christopher R. Vakoc, Linda Van Aelst and Mikala Egeblad, 22 February 2024, Cancer Cell.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.01.013

The study was funded by the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Cancer Research, the Cancer Research Institute, and the German Research Foundation.

New research reveals that stress promotes cancer metastasis by causing neutrophils to form structures that facilitate the disease’s spread. This finding highlights the importance of incorporating stress reduction into cancer treatment and suggests new avenues for preventing cancer metastasis through targeted therapies.

Stress is an unavoidable aspect of life. However, excessive stress can have detrimental effects on our health. Prolonged stress elevates the risk of developing heart disease and experiencing strokes. It may also help cancer spread. How this works has remained a mystery—a challenge for cancer care.

Xue-Yan He, a former postdoc in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Adjunct Professor Mikala Egeblad’s lab, says, “Stress is something we cannot really avoid in cancer patients. You can imagine if you are diagnosed, you cannot stop thinking about the disease or insurance or family. So it is very important to understand how stress works on us.”

For a recent CSHL Cancer Center study, Adjunct Professor Mikala Egeblad (now a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor with Johns Hopkins University) and postdoc Xue-Yan He (now Assistant Professor of Cell Biology & Physiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis) teamed with CSHL Professor Linda Van Aelst. Above: lung cancer metastasis in a mouse that underwent experiments designed to simulate the stress that cancer patients experience. Credit: Egeblad lab/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Now, He and Egeblad may have reached a breakthrough in understanding exactly that. Working with CSHL Professor Linda Van Aelst, they discovered that stress causes certain white blood cells called neutrophils to form sticky web-like structures that make body tissues more susceptible to metastasis. The finding could point to new treatment strategies that stop cancer’s spread before it starts.

Stress-Induced Metastasis in Mice

The team arrived at their discovery by mimicking chronic stress in mice with cancer. They first removed tumors that had been growing in mice’s breasts and spreading cancer cells to their lungs. Next, they exposed the mice to stress. What He observed was shocking.

“She saw this scary increase in metastatic lesions in these animals. It was up to a fourfold increase in metastasis,” Egeblad recalls.

Cancer spread faster and more furiously in stressed mice (middle column) than in a control group (left column). By comparison, cancer cells in stressed mice treated with an enzyme called DNase I (right column) were largely non-proliferating, and the treatment caused a significant reduction in stress-induced metastasis. Credit: Egeblad lab/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

The team found that stress hormones called glucocorticoids acted on the neutrophils. These “stressed” neutrophils formed spider-web-like structures called NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps). NETs form when neutrophils expel DNA. Normally, they can defend us against invading microorganisms. However, in cancer, NETs create a metastasis-friendly environment.

Potential for New Treatment Strategies

To confirm that stress triggers NET formation, leading to increased metastasis, He performed three tests. First, she removed neutrophils from the mice using antibodies. Next, she injected a NET-destroying drug into the animals. Lastly, she used mice whose neutrophils couldn’t respond to glucocorticoids. Each test achieved similar results. “The stressed mice no longer developed more metastasis,” He says.

Notably, the team found that chronic stress caused NET formation to modify lung tissue even in mice without cancer. “It’s almost preparing your tissue for getting cancer,” Egeblad explains.

To Van Aelst, the implication, though startling, is clear. “Reducing stress should be a component of cancer treatment and prevention,” she says.

The team also speculates that future drugs preventing NET formation could benefit patients whose cancer hasn’t yet metastasized. Such new treatments could slow or stop cancer’s spread, offering much-needed relief.

Reference: “Chronic stress increases metastasis via neutrophil-mediated changes to the microenvironment” by Xue-Yan He, Yuan Gao, David Ng, Evdokia Michalopoulou, Shanu George, Jose M. Adrover, Lijuan Sun, Jean Albrengues, Juliane Daßler-Plenker, Xiao Han, Ledong Wan, Xiaoli Sky Wu, Longling S. Shui, Yu-Han Huang, Bodu Liu, Chang Su, David L. Spector, Christopher R. Vakoc, Linda Van Aelst and Mikala Egeblad, 22 February 2024, Cancer Cell.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.01.013

The study was funded by the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Cancer Research, the Cancer Research Institute, and the German Research Foundation.