What the Midterms Told Us About the Future of Climate Action

It’s that time of year again, when climate hawks gather around to read the tea leaves about what happened in U.S. national elections. This year’s climate campaign trail, for Democrats, was a lot different than previous years, thanks to the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S.’s first national comprehensive climate bill. For once, Democrats had a concrete climate success to campaign on during the midterms—and the results point to an interesting, if not groundbreaking, political future for climate action.

Despite years of insistence from climate hawks that climate can and should be a bipartisan issue, that idea still hasn’t manifested at a national level; any and all Democratic successes, especially in Congress, are still, theoretically, better than Republican ones for large-scale climate action. (Not excusing in the slightest how badly Dems have fumbled the ball at home and abroad—just saying that the bare minimum is better than the alternative.) In that sense, there are some great signs for climate progress in the preliminary results this week.

Lots of ink has been spilled about whether or not climate as an issue gets voters to the polls; the jury still seems to be out on that for this cycle. But this election may actually prove a negative here, that climate is not a bad thing to campaign on. As journalist Jael Holzman pointed out on Twitter, the passage of the IRA dovetailed this year with soaring energy prices, usually a terrible sign in the midterms for the incumbent party. Republicans around the country have been (falsely) campaigning on the idea that Biden’s focus on climate action is what’s driving energy prices up. These midterm results may signal that that strategy is outdated and that climate action can’t be used to drag down Democrats, even in the face of a global energy crisis.

Now let’s turn to the individual results. Some of the most worrisome climate deniers in this election cycle—including Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania and Blake Masters in Arizona—were defeated by their Democratic opponents. And some other incumbent deniers, like Rep. Lauren Boebert in Colorado, are in races that were still too close to call as of Thursday morning, potentially delivering Democratic victories and keeping some real climate loonies out of power. (I personally would love for Boebert, who not only has a tenuous grasp of science but a husband who works in the oil and gas industry, to not be able to vote on climate policy any more.)

There were some losses and some still up-in-the-air races that are keeping us on the edge of our seat, including the upcoming runoff in Georgia between Raphael Warnock (D) and Herschel Walker (R). In Texas, one of the most important oil- and gas-producing regions in the world, Gov. Greg Abbott won his reelection, while the climate change-denying Texas Railroad Commissioner Wayne Christian, whose Commission regulates the industry, also kept his job. The potential for climate action may look slightly rosier than before at a national level, but the powerful politicians controlling the U.S.’s fossil fuel hub have proven themselves to be staunch defenders of the industry in the past—and influencers of other problematic pro-fossil fuel policies in other states.

G/O Media may get a commission

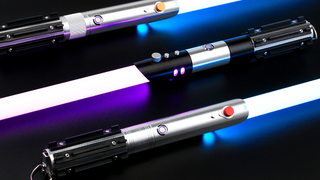

*lightsaber hum*

SabersPro

For the Star Wars fan with everything.

These lightsabers powered by Neopixels, LED strips that run inside the blade shape that allow for adjustable colors, interactive sounds, and changing animation effects when dueling.

This is also the first election I can remember in which the goalposts on politicians’ perspectives on climate science seem to have moved. For years, the calling card for Democrats has been for voters to elect politicians who “believe in science;” Donald Trump’s famously terrible grasp on climate science only intensified that position. It’s telling that many of the Republicans campaigning for election or reelection, with some notable exceptions, have either shifted their tune on climate science or were never hardline deniers to begin with.

Much has been made of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s reelection, with many outlets projecting that he’s looking ahead to a 2024 presidential run. DeSantis, whose own state has been hit especially hard by climate change, is, notably, not a climate change denier. That doesn’t mean his climate policies are any good: He has focused on preparation and resilience against the impacts of global warming while encouraging continued fossil fuel use.

This form of denial-lite is becoming more common among contrarians and conservatives: accepting the climate science but still refusing to engage with the solutions we actually need—like ending fossil fuel use quickly—or insisting that oil and gas can be part of our future. If I had to guess, the tide will begin to turn for Republicans toward becoming more like DeSantis, and if Democrats plan to run on climate change as an issue in the future, they’ll need to prepare more for opponents like these. Heck, if we want to do anything else at a national level on climate, regardless of political party, climate hawks need to figure out a way to combat this new line of reasoning.

And despite the promising signs for climate action, this year really hit home the futility of trying to separate climate action from the overall political conversation as some sort of nonpartisan issue—even for me, a climate journalist and someone who thinks about this stuff every day. Sure, the IPCC’s warnings are increasingly dire, but people across the country are losing access to abortion care now. Yes, DeSantis’s climate policies are problematic, but he’s also at the forefront of an incredibly cruel wave of anti-LGBTQ policies that I’m terrified could become national if he wins the presidency. I’ve written before about how climate and these issues are intimately connected thanks to the dark money fueling opposition on the right. American fascism is alive, well, and rising; in the face of that, pushing climate change as its own issue without recognizing the connections to social justice is an outdated strategy.

It’s that time of year again, when climate hawks gather around to read the tea leaves about what happened in U.S. national elections. This year’s climate campaign trail, for Democrats, was a lot different than previous years, thanks to the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S.’s first national comprehensive climate bill. For once, Democrats had a concrete climate success to campaign on during the midterms—and the results point to an interesting, if not groundbreaking, political future for climate action.

Despite years of insistence from climate hawks that climate can and should be a bipartisan issue, that idea still hasn’t manifested at a national level; any and all Democratic successes, especially in Congress, are still, theoretically, better than Republican ones for large-scale climate action. (Not excusing in the slightest how badly Dems have fumbled the ball at home and abroad—just saying that the bare minimum is better than the alternative.) In that sense, there are some great signs for climate progress in the preliminary results this week.

Lots of ink has been spilled about whether or not climate as an issue gets voters to the polls; the jury still seems to be out on that for this cycle. But this election may actually prove a negative here, that climate is not a bad thing to campaign on. As journalist Jael Holzman pointed out on Twitter, the passage of the IRA dovetailed this year with soaring energy prices, usually a terrible sign in the midterms for the incumbent party. Republicans around the country have been (falsely) campaigning on the idea that Biden’s focus on climate action is what’s driving energy prices up. These midterm results may signal that that strategy is outdated and that climate action can’t be used to drag down Democrats, even in the face of a global energy crisis.

Now let’s turn to the individual results. Some of the most worrisome climate deniers in this election cycle—including Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania and Blake Masters in Arizona—were defeated by their Democratic opponents. And some other incumbent deniers, like Rep. Lauren Boebert in Colorado, are in races that were still too close to call as of Thursday morning, potentially delivering Democratic victories and keeping some real climate loonies out of power. (I personally would love for Boebert, who not only has a tenuous grasp of science but a husband who works in the oil and gas industry, to not be able to vote on climate policy any more.)

There were some losses and some still up-in-the-air races that are keeping us on the edge of our seat, including the upcoming runoff in Georgia between Raphael Warnock (D) and Herschel Walker (R). In Texas, one of the most important oil- and gas-producing regions in the world, Gov. Greg Abbott won his reelection, while the climate change-denying Texas Railroad Commissioner Wayne Christian, whose Commission regulates the industry, also kept his job. The potential for climate action may look slightly rosier than before at a national level, but the powerful politicians controlling the U.S.’s fossil fuel hub have proven themselves to be staunch defenders of the industry in the past—and influencers of other problematic pro-fossil fuel policies in other states.

G/O Media may get a commission

*lightsaber hum*

SabersPro

For the Star Wars fan with everything.

These lightsabers powered by Neopixels, LED strips that run inside the blade shape that allow for adjustable colors, interactive sounds, and changing animation effects when dueling.

This is also the first election I can remember in which the goalposts on politicians’ perspectives on climate science seem to have moved. For years, the calling card for Democrats has been for voters to elect politicians who “believe in science;” Donald Trump’s famously terrible grasp on climate science only intensified that position. It’s telling that many of the Republicans campaigning for election or reelection, with some notable exceptions, have either shifted their tune on climate science or were never hardline deniers to begin with.

Much has been made of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s reelection, with many outlets projecting that he’s looking ahead to a 2024 presidential run. DeSantis, whose own state has been hit especially hard by climate change, is, notably, not a climate change denier. That doesn’t mean his climate policies are any good: He has focused on preparation and resilience against the impacts of global warming while encouraging continued fossil fuel use.

This form of denial-lite is becoming more common among contrarians and conservatives: accepting the climate science but still refusing to engage with the solutions we actually need—like ending fossil fuel use quickly—or insisting that oil and gas can be part of our future. If I had to guess, the tide will begin to turn for Republicans toward becoming more like DeSantis, and if Democrats plan to run on climate change as an issue in the future, they’ll need to prepare more for opponents like these. Heck, if we want to do anything else at a national level on climate, regardless of political party, climate hawks need to figure out a way to combat this new line of reasoning.

And despite the promising signs for climate action, this year really hit home the futility of trying to separate climate action from the overall political conversation as some sort of nonpartisan issue—even for me, a climate journalist and someone who thinks about this stuff every day. Sure, the IPCC’s warnings are increasingly dire, but people across the country are losing access to abortion care now. Yes, DeSantis’s climate policies are problematic, but he’s also at the forefront of an incredibly cruel wave of anti-LGBTQ policies that I’m terrified could become national if he wins the presidency. I’ve written before about how climate and these issues are intimately connected thanks to the dark money fueling opposition on the right. American fascism is alive, well, and rising; in the face of that, pushing climate change as its own issue without recognizing the connections to social justice is an outdated strategy.